DepthReading

A mirage, come true

The Silk Road city of Dunhuang is an oasis shaped by the sands of time that has survived and thrived in the desert for millennia. The ancient refuge in one of the planet's toughest terrains sired an international settlement in no-man's land and continues to lure travelers from around the world.

Dunhuang appears as if a mirage come true in the desert - an oasis, an island of water in a sea of sand that seems as if it could not be but is. Camels once functioned like cargo boats that floated across the dunes that still crash like waves in the ocean of parched earth that led to this refuge constructed at the crossroads of thirst for water and hunger for trade.

The intersection of two major Silk Road routes in the Gobi, near the edge of the Taklimakan Desert, whose name translates as "place of no return", enabled passage through one of the least-hospitable swaths of the planet's surface.

Not only could people survive the sojourns across the wastelands - cross-border exchanges would flourish as a result.

Dunhuang sprang from its springs to become an international trade hub, regional garrison and place of pilgrimage for Buddhists.

Today, the city in Northwest China's Gansu province is experiencing a revival that's enhanced by the Belt and Road Initiative.

Visitors explore the desert at the edge of the city - and that edge, as viewed from the dunes, is abrupt. Poplars tower on one side of the road, dividing town from barren dunes. There's no transition between tall trees and pure sand.

Visitors to the 200-square-kilometer Mingsha Mountain Crescent Spring area still ride camels across the sand mounds that undulate like the backs of the beasts of burden that plod atop them.

Some opt for wheels rather than hooves and zoom across the dunes in buggies and all-terrain vehicles. They can also sled down the slopes in bamboo toboggans or soar above the rolling landscapes in three-wheeled, propeller-powered helicopter gliders.

The area's Crescent Moon Lake appears on Earth as if a reflection of the sky shimmering on the ground. The sliver of brilliant blue that streaks the sallow sands and the trees that stand at the edge of the water sickle's blade appear otherworldly, as if an illusion, as if impossible.

But its appeal is very real.

The water body is set among the Singing Sand Dunes, so named because they resonate in the wind.

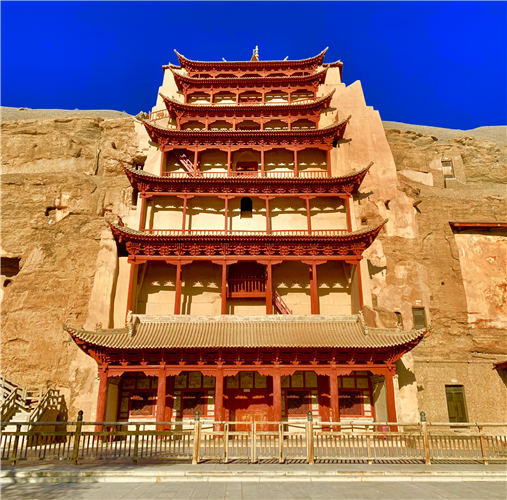

Nearby, Dunhuang's Silk Road legacy is literally set in stone at the Mogao Grottoes.

Legend has it that monk Yue Zong sat sweltering in the searing sunlight near a river in front of a mountain, admiring the landscape's exceptional feng shui, in 366 AD. He decided to dig a dwelling at the point where the sun sank behind the crest as it set.

Others followed suit over the following millennium, whittling a honeycomb of caverns inhabited by aristocrats, refugees and monks.

The hundreds of chambers serve as unintended time capsules since they were, in the truest sense, shaped by the periods during which they were excavated and renovated.

The statues and frescoes not only venerate Buddha but also record the history of exchanges between China and dozens of nations to its west.

The caverns also housed the largest collection of historical documents found along the Silk Road - 40,000 writings and artworks spanning several centuries and languages hidden in a secret passage behind a fake wall.

Cave No 249's Western Wei Dynasty (535-556) murals and Qing-era (1644-1911) sculptures depict Indians interacting with local ethnic groups. A Buddha wears a Greek robe and stands next to a Hindu god with 13 heads and a serpentine body.

No 292's Sui Dynasty (581-618) Buddhas don Persian clothing dyed with Afghan pigments that were then more valuable than gold.

Cave 323's frescoes convey the Silk Road's origin story by portraying the travels of envoy Zhang Qian, whose westward explorations over 2,000 years ago led to the trade route's creation.

Indeed, Mogao's treasure trove of historical riches makes it an archeological Aladdin's cave. (The original fable is actually set in an unspecified Chinese desert settlement instead of in the Middle East, as is commonly believed.)

Dunhuang's legacy as an intersection of civilizations has survived beyond the centuries of the Silk Road.

And it seems poised to flourish further with the Belt and Road Initiative, especially after the second BRI forum in Beijing, which opens on Thursday.

Indeed, visitors will discover the desert city is still being shaped by the sands of time and the crossroads of cultures.

And they may find explorations of the area are best undertaken atop the backs of camels, as has remained customary for millennia and will likely continue in the years to come.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: