The 13th century is a period when Silk Road accounts from European travellers starts to become much more common than before. Still, they only make up a fraction of all the written accounts, as the vast majority of the surviving 13th century Silk Road texts was authoried by Asian merchants, diplomats and monks/pilgrims.

Below, you will find a few examples of people who travelled on the Silk Road during the 13th century and wrote detailed accounts about it.

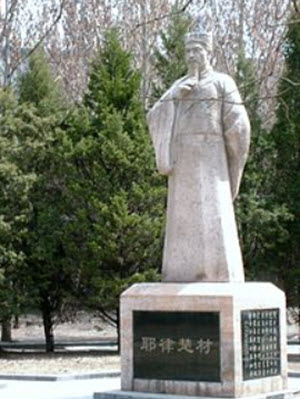

1219-1225: Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai

Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai was a renowned Kithan statesman and poet who became one of Genghis Khan’s trusted advisors. From 1219, he travelled with Gehis Khan and the army through parts of Central Asia, visiting places such as Altai, the Ili valley, Talas, Samarkand, and Buhara. Eventually, they returned via Tienshan, Urumqi, Turfan, and Hami. Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai wrote the book Xi Yue Lu (The Travel Record to the West) and also quite a lot of poetry, including some poems about the mesmerizing Silk Road city of Buhara in Uzbekistan.

Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai was a renowned Kithan statesman and poet who became one of Genghis Khan’s trusted advisors. From 1219, he travelled with Gehis Khan and the army through parts of Central Asia, visiting places such as Altai, the Ili valley, Talas, Samarkand, and Buhara. Eventually, they returned via Tienshan, Urumqi, Turfan, and Hami. Yeh-lü Ch’u-ts’ai wrote the book Xi Yue Lu (The Travel Record to the West) and also quite a lot of poetry, including some poems about the mesmerizing Silk Road city of Buhara in Uzbekistan.

1245-1247 & 1249-1251: Andrew of Longjumeau

The European Andrew of Longjumeau, a member of the Christian Dominican Order, was sent as a papal enovy to the Mongols in 1245. He travelled from the Holy Land to Trabriz, in today’s northern Iran.

On his second trip, which started in 1249, Andrew of Longjumeau went much farther. This time, he was accompanied by a larger group that included his own brother William. Exacty which route they took is unclear, but they did reach the Mongols living in inner Asia, ruled by Khan Güyüg’s widow Oghul Qaimish.

Information about Andrew of Longjumeau’s journeys has been preserved in Matthew Paris’s “Chronica Majora”.

1220-1221 AD: Chung tuan (Wu-ku-sun)

In 1220, the Jin Emperor sent his diplomat Chung tuan as an embassador to Ghengis Khan. Accompanied by a man named An T’ing chen, Chung tuan travelled to the Hindukush Mountains.

1221-1224 AD: K’iu Ch’ang Ch’un & Li Chi Ch’ang

In 1221, the renowned Taoist monk K’iu Ch’ang Ch’un was summoned to the court of Ghengis Khan. Born in 1148, Ch’un was an old man at this point, but he carried out the journey anyway, accompanied by Li Chi Ch’ang. The route went through the Altai Mountains and the Tienshan Mountains, through Kyrgyzstan and then to Samarkand. From Samarkand, they continued into north-eastern Iran and Afghanistan.

Li Chi Ch’ang kept a diary during the journey and his notes were published under the title “Hsi Yu Chi” in 1228, and included in the Tao tsang tsi yao.

1245-1248 AD: Ascelinus and Simon from San Quentin

Ascelinus and Simon from San Quentin, both members of the Dominican Order, were sent by the Pope as envoys to the Mongols in 1245.

On their way back, bringing Mongol envoys to the Pope, they travelled through places such as Tabriz, Mosul, Allepo, Antioch, and Acre.

Simon wrote an account of their experiences, but it is not available in English. Some information is included in Matthew Paris’s “Chronica Majora”.

1245-1247 AD: Giovanni da Pian del Carpine& Benedykt Polak

In 1245, these two Franciscan monks were sent by Pope Innocent IV as envoys to the Mongol Khan. They travelled through the lands of Golden Horse ruler Khan Batu to get to the Karakorum area, where they were present as Güyüg was proclaimed as the new Great Khan.

In 1245, these two Franciscan monks were sent by Pope Innocent IV as envoys to the Mongol Khan. They travelled through the lands of Golden Horse ruler Khan Batu to get to the Karakorum area, where they were present as Güyüg was proclaimed as the new Great Khan.

Giovanni wrote the book Historia Mongalorum (History of the Mongols).

1253-1255 AD: Willem from Ruysbroeck

This Franciscan missionary from Flanders accompanied King Louis IX of France on the Seventh Crusade in 1248. In 1253, the king ordered him to travell as a missionary to the Tatars with the goal of converting them to Christianity. Willem first headed for Constantinopel to confer with Baldwin of Hainaut, since he had recently visited Karakorum on behalf of the Latin Emperor.

After obtaining information from Baldwin, Willem followed two routes previously used by Friar Julian (from Hungary) and Friar Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, respectively. Willem did not travell alone; he was accompanied by a group that, among others, included an interpretor that would help with communications in the foreign lands.

Willem and his group travelled through the Crimean two Sudak and crossed the River Don. Nine days after crossing Don, they reached the Kipchak Khanate ruler Sartaq Khan. Sartaq Khan told Willem about the route he should take to reach the khan’s father Batu Khan at Sarai near tye River Volga.

Batu Khan, the Mongol ruler of the Volga region, was not interested in being converted to Christianity, but he told the party how they should journey to reach Möngke Khan – the Great Khan of the Mongols. On 16 September 1253, Willem and his group left on horseback to do the 9,000 km long trip to Karakorum.

In Karakorum, they were granted an audience with the Great Khan on 4 January, 1254. Willem’s descriptions of Karakorum are very detailed, and lets us know that this was a walled city with temples and markets. It was a cosmopolitan place, with large enough numbers of Muslim and Chinese craftsmen for them to have established their own separate quarters.

In Karakorum, they were granted an audience with the Great Khan on 4 January, 1254. Willem’s descriptions of Karakorum are very detailed, and lets us know that this was a walled city with temples and markets. It was a cosmopolitan place, with large enough numbers of Muslim and Chinese craftsmen for them to have established their own separate quarters.

In July 1254, Willem and his group started on their long journey home. After returning, Willem presented King Louis IX with the 40 chapter report “Itinerarium fratris Willielmi de Rubruquis de ordine fratrum Minorum, Galli, Anno gratiae 1253 ad partes Orientales”.

This report included a lot of valuable information and became one of the great masterpieces of medieval geograpical literature. It did for instance demonstrate that the Caspian Sea was an inland sea and did not go all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Until then, this had been a long-standing question in continental Europe, especially in the south where the travels of Scandinavian explorer Ingvar the Far-Travelled were largely unknown.

1254-1255 AD: Hayton I & Kirakos Gandsaketsi

In 1254, King Hayton I of Little Armenia travelled through the Caucaus and the lands of Khan Batu to reach the Great Khan Möngke in Karakorum. With him was Kirakos Gandsaketsi who wrote an account of the journey. To get home, they travelled via Samarkand, Bukhara and Tabriz.

1259-1260 AD: Ch’ang Te

Soon after Hülegü’s conquest of the Abbasid Chaliphate, his brother the Great Khan Möngke sent him the envoy Ch’ang Te. Ch’ang Te wrote a text that is both a travel journal and a second-hand account of Hülegü’s military campaigns.

1260-1295 AD: The Polos

For information about the travels of Niccoló, Maffeo and Marco Polo, please visit the article Marco Polo and his travels on this site.

1275-1279 & 1287-1288 AD: Markos and Rabban Bar Sauma

This was two Önggüd (Turkic) Nestorian monks who travelled from Qubilai Khan’s northern capital Tai-tu to the Middle East via the Silk Road’s southern branch, passing through places such as Khotan and Kashgar.

Their aim was to reach Jerusalem, but they never got that far. While in the Mongol Ilkhanid lands, they became active in church politics, and Markos was elected head of the Nestorian church, becoming Patriarch Mar Yaballlah III.

Their aim was to reach Jerusalem, but they never got that far. While in the Mongol Ilkhanid lands, they became active in church politics, and Markos was elected head of the Nestorian church, becoming Patriarch Mar Yaballlah III.

In 1287, Rabban Bar Sauma travelled west without Markos, as an emissary of the Ilkhanid ruler Arghun. His task was to form an alliance that would help Arghun fight the Mamluks.

Sauma’s writings are especially interesting since they provide a different perspective on European customs and rites than most other writers of this era.

1279-1328 AD: Giovanni da Montecorvino

This was an Italian Franciscan missionary, traveller and statesman who founded early Roman Catholic missions in India and China. He eventually became archbishop of Peking / Beijing.

After being active in Armenia and Persia, Giovanni da Montecorvino travelled from Tabriz in 1291, heading for China. Exactly when he arrived in Beijing is unclear, but it was most likely after the death of Kublai Khan in 1294.

Giovanni remained in China until his death. Much of what we know about his journeys and experiences in the East are from his letters, since he did not publish any travel journey or similar.

14th century travelers on the Silk Road

Circa 1316-1330 AD: Odoric Mattituzzi from Pordeone

Odoric Mattituzzi (1286-1331) was an Italian Franciscian friar and missionary explorer who travelled to India and China.

Odoric Mattituzzi (1286-1331) was an Italian Franciscian friar and missionary explorer who travelled to India and China.

Odoric journeyed via Constantinople and the Black Sea to reach Persia, and from there by ship to India in the early 1320s. In India, he embarked on a ship that took him around southeast Asia to the coast of China.

After living for several years in Beijing, Odoric travelled mostly overland to get back to Venice. He claimed to have gone through Tibet, but if this is actually true remains unclear.

Many of the marvelous stories included in John Mandevilles highly successful book “The Travels of Sir John Mandeville” are fanciful and embroidered tales based on Odoric’s texts.

1325-1354 AD: Shams al-Din Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad Ibn Battuta

This was an explorer of Tangier origin who travelled across North Africa, through Euroasia and all the way to China and back in 1325-1354. Afterwards, he dictated his experiences and knowledge to Ibn Djuzayy who wrote it down in the year 1354-1357. His tales from Anatolia, the lands of the Golden Horde, and southern India are considered especially valuable.

1339-1353 AD: Giovanni de’ Marignolli

This was a Franciscan from Florence who was sent by the Pope as a delegate to the Yüan (Mongol) Emperor of China.

This was a Franciscan from Florence who was sent by the Pope as a delegate to the Yüan (Mongol) Emperor of China.

Giovanni de’ Marignolli travelled through the Golden Horde lands via the Black Sea, and then onwards to Beijing and Shang-tu, arriving in August 1342. His exact route remains unclear, but it probably went south of the Aral Sea at Urgench and then north of the Taklamakan Desert.

After three years in China, Giovanni travelled onboard a ship to Hormuz and then overland to the Levant.

15th century travelers on the Silk Road

1403-1406 AD: Ruy Gonzales de Clavijo & Alfonso Paez

These were ambassadors of the Spanish King Enrique III de Castilla, sent to the Turco-Mongol conqueror Amur Timur, founder of the Timur Empire. A third envoy by the name Gómez de Salazar travelled with them initially, but he died en route.

The two Spanish embassadors first tavelled from the Mediterranean to Constantinople, then via the Black Sea to Trebizond, and then overland through Tabriz, Balkh and Kesh to reach Samarkand where Amur Timur was.

On their trip back, they passed through Bukhara, an important center of commerce along the Silk Road in Uzbekistan.

Soon after returning to Europe in 1406, Clavijo wrote down an account of his experiences, which became a very important source of information for future travellers along the western section of the Silk Road.

1419-1422 AD: Ghiyathuddin Naqqash

This was an artist sent as an embassador to Beijing in 1419 by the Timurid ruler Shahruhk and his son Prince Mirza. He travelled a route that took him north of the Tarim Basin, through places such as Turfan, Jiayuguan, and Suzhou to get to Beijing. On his way back, he passed through Kashgar.

1435-1439 AD: Pero Tafur

Pero Tafur, an Andalusian native, travelled from Spain to the Eastern Mediterranean and back in the 1430s. Examples of places he visited are Egypt, the Black Sea region, and the declining Constantinople.

1436-1452 and 1473-1479 AD: Giosofat Barbaro

In 1436, the merchant Giosofat Barbaro travelled to Tana, located in the delta of the River Don, and he stayed there until the early 1450s. He wrote about his experiences, the Black Sea region in general, and even the distant Muscovy (which he never visited himself).

In 1436, the merchant Giosofat Barbaro travelled to Tana, located in the delta of the River Don, and he stayed there until the early 1450s. He wrote about his experiences, the Black Sea region in general, and even the distant Muscovy (which he never visited himself).

In 1473, he embarked on a new journey – this time as an ambassador sent to Persia. He stayed in Persia until 1479 and wrote a detailed official report about it.

1466-1472 AD: Afanasii Nikitin

Afanasii Nikitin was a merchant from the Russian city Tver, located along the upper part of the River Volga. He travelled through Persia to India and lived in India for over a year and a half. He died on his way back, not very far from Tver.

In his texts about travelling, Afanassi Nikitin recommended Christian merchants to profess Islamic beliefs while travelling and doing business on the Silk Road.

1474-1477 AD: Ambrogio Contarini

Ambrogio Contarini was a Venetian ambassador to Persia. He travelled through Central Europe, Ukraine, Crimea, and the Caucasus. In Persia, he spent time in placed such as Tabriz and Isfahan.

When it was time to head back home, he travelled via Muscovy and Poland.

16th century travelers on the Silk Road

Contents [show]

1490s – 1530: Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur

A direct descendant of Timur, the young Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur lived in Central Asia and Afghanistan, before settling down in India where he founded the Mughal Empire.

A direct descendant of Timur, the young Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur lived in Central Asia and Afghanistan, before settling down in India where he founded the Mughal Empire.

His texts are from the perspective of a Muslim from Central Asia and thus bring an interesting new perspective for those who have mostly read European Christian or Chinese Buddhist accounts about this region.

Various journeys between 1546 and 1564: Anthony Jenkinson

Anthony Jenkinson was a representivative of the English Muscovy Company and as such travelled extensively for them from 1557 and onwards. Prior to this, he traveled widely in the Mediterranean and the Levant.

In 1557, the English Muscovy Company sent him to the imortant Uzbekistan Silk Road trading hub Bukhara, which he reached by travelling via the White Sea and Moscow, down the River Volga, and across the Caspian Sea. He returned back by the same route in 1560.

In 1557, the English Muscovy Company sent him to the imortant Uzbekistan Silk Road trading hub Bukhara, which he reached by travelling via the White Sea and Moscow, down the River Volga, and across the Caspian Sea. He returned back by the same route in 1560.

In 1561-1564, Jenkinson repeated this journey to the Caspian Sea, but then headed for Persia with the aim of negotiating trade agreements for the Company. One winter he stayed in Kazvin, learning about the spice trade from Indian merchants.

Various journeys between 1579 and 1584: Jon Newbery

John Newberry was a London-based English merchant who undertook three major trips.

1579: To the Levant

1580-1582: From the Levant through Mesopotamia to the Persian Gulf and Hormuz, and then back through central Persia, southernmost Caucasus, Anatolia, and Eastern Europe.

1583-1584: On this third major trip for Jon Newberry, he went all the way to the Mughal court in India. For part of the journey, fellow Londoner Ralph Fitch travelled with him.

Newberry died on his way home from India.

1583-1591: Ralph Fitch

Ralph Fitch was an English merchant who traveled as far as Malacca in Malaysia. Starting out in 1583, he traveled together with Jon Newberry during part of the journey.

Fitch traveled to the Levant and Mesopotamia, continued through northern India, and went as far as Malacca before turning back home via the Persian Gulf.

When he came back to London in 1591, he found out that his property had been divided among his heirs since he was presumed dead.

He later left London for Aleppo.

17th century travelers on the Silk Road

Early 17th century: Benedict Goës

In the late 16th, Benedict Goës, a Portuguese Jesuit Benedict, joined a mission to the Mughal Emperor Akbar. Eventually, he was elected by the Jesuit leadership to go on a journey to China, via Kashgar. One of the reasons for choosing Goës was the fact that he spoke Persian.

Goës embarked on the journey overland in the early 17th century, heading northwest into Afghanistan and then north through Hindu Kush. After reaching the headwaters of the Amu Darya, he followed a route east to Sarikol, before going through places such as Yarkand and Kashgar. He travelled along the outskirts of the Taklamakan Desert region, but died before reaching Beijing.

1615-1616: John Crowther and Richard Steele

John Crowther and Richard Steele were both agents for the British East India Company. In 1615, they were already in northern Indian, when they embarked on a journey from Agra, the Mughal capital, to Isfahan, the Safavid capital.

John Crowther and Richard Steele were both agents for the British East India Company. In 1615, they were already in northern Indian, when they embarked on a journey from Agra, the Mughal capital, to Isfahan, the Safavid capital.

They travelled overland via Kandahar, and their notes from the journey show how relatively safe the land route was considered as long as you were within lands controlled by Mughals and Safavids. This helped keep the Silk Road active even during the famous Age of Sail. By taking the Silk Road, these Englishmen could also avoid using any of the many Indian Ocean seaports that were under Portuguese control.

After leaving Isfahan, Crowther returned to India, while Steele travelled overland all the way to the Mediterranean. Only between Marseilles and England did he go by boat.

Six journeys between 1629 and 1675: Jean Baptiste Tavernier

Jean Baptiste Tavernier was a French merchant and jeweler who made six major voyages through Persia in the 17th century. Examples of places that he visited are the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Persia and Mughal India. He developed good connections with various Asian merchant communities, such as the Armenian merchants doing business in Persia.

Three journeyes between 1633 and 1643: Adam Olearius

Adam Olearius was a Protestant Christian educated at the University of Leipzig.

First journey: 1633-1635. As secretary to the Embassy of Holstein, Adam Olearius travelled to Moscow.

Second journey: 1635-1639. As secretary to the Embassy of Holstein, Olearius travelled through Moscovy to Persia. He spent a year in Persia.

Third journey: 1643. Olerarius returned to Moscow as the Ambassador of Holstein.

- Olearius left detailed accounts of both Muscovy and Persia. First published in 1647, a revised German edition was launched in 1656, followed by various translations.

Two journeys between 1664 and 1677: John Chardin

Jean-Baptiste Chardin, known in English as John Chardin, was a French Hugenot jeweller who travelled to the Caucasus, Persia and India. His first longer sejour to the East was in 1664-1667, his second lasted from 1671 to 1677. He spoke Persian and wrote one of the most notable European accounts of Safavid Persia.

In England, he was an expert on the Middle East. He could not live in France due to the persecution of Protestants there.

1682-1693: Hovhannes Joughayetsi

This Armenian merchant travelled from New Julfa to Northern India and Tibet. (New Julfa was an Armenian suburb of the city Isfahan in today’s Iran.) He spent five years in Lhasa, the administrative and religious capital of Tibet.

His writings include a lot of information about the well-developed Armenian trading network of this era, including trading routes that went through the Safavid and Mughal empires.