DepthReading

In the Time of the Rosetta Stone

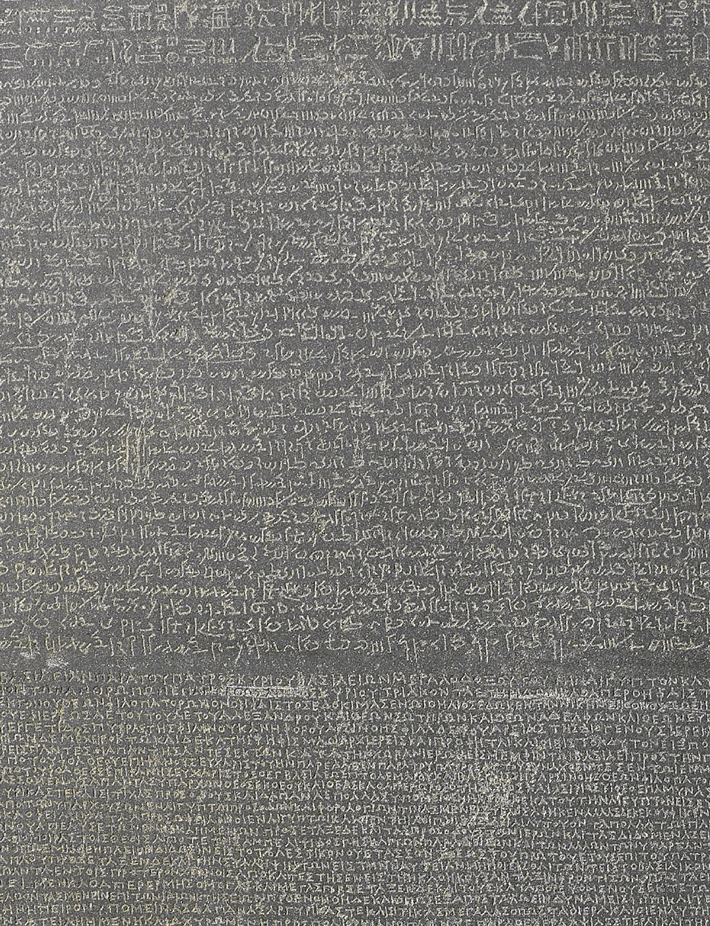

The Rosetta Stone is inscribed with the Third Memphis Decree, written in three different scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphics (top), Egyptian Demotic (middle), and (bottom) Ancient Greek.

While many people may be familiar with the basics of the Rosetta Stone, few perhaps know what the text says or understand the events that influenced the stela’s creation. The stone was once part of a series of carved stelas that were erected in locations throughout Egypt amid events of the Great Revolt (206–186 B.C.). These monuments were inscribed with the Third Memphis Decree, which was issued by Egyptian priests in Memphis in the year 196 B.C. to celebrate Ptolemy V’s achievements and affirm the young king’s royal cult.

It is sometimes forgotten that the Ptolemaic rulers were actually Greek. Ptolemy V (r. 205-180 B.C.) came to power as a child of six when his father, Ptolemy IV (r. 222-205 B.C.), died. Ptolemy V was no more than 14 when the decree was written.

The decree, nonetheless, chronicled his victory in the Nile Delta over a faction of native Egyptians who were violently rebelling against Hellenistic rule. While specifics of the revolt remain obscure today, the little that is known has been drawn from a few surviving texts and inscriptions, including the Rosetta Stone. Until recent excavations at the ancient city of Thmuis, located in an area where some of the bloody events are known to have occurred, hardly any archaeological evidence of the revolt existed. But at Thmuis, archaeologists have encountered signs of violent destruction and death, which they believe are the first definitive remains associated with the uprising. In addition, these discoveries are leading to a new and more subtle understanding of the Rosetta Stone—one in which it is viewed less as linguistic serendipity and more as a propagandistic document created for all to see in a tumultuous time.

In the ancient city of Thmuis, at Tell Timai in the Nile Delta of northern Egypt, archaeologists have encountered the first tangible evidence corresponding to the time and events of the Great Revolt alluded to on the Rosetta Stone. There, in a layer characterized by broad devastation, a number of pottery kilns (left) were systematically destroyed and later built over. This unburied male human skeleton (right) was discovered lying amid the rubble. It bears unmistakable signs of a violent death.

Thmuis is buried beneath Tell Timai in the Nile Delta of northern Egypt around 40 miles from the Mediterranean coast. A tell is an artificial mound of earth and debris, common in the Near East, formed through long periods of occupation and abandonment of the same site. Thmuis, once located along the now-defunct Mendesian branch of the Nile, was originally established as a smaller companion settlement to the important port city of Mendes, just under half a mile to the north. While Mendes was a significant religious and political center dating back as long as 5,000 years, Thmuis, literally meaning “new land,” was founded around the middle of the first millennium B.C. as an industrial suburb. The Mendes-Thmuis district lies along an important transit and trade corridor connecting the Mediterranean Sea with Upper Egypt and was renowned in antiquity for its production of perfume. Much of the perfume manufacturing process, from the infusion of olive oil with special scented flowers and herbs, to the production of small ceramic oil vessels, or aryballoi, was centered in Thmuis.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: