A well-planned city

One of the most remarkable revelations was that this city was nicely aligned in a massive grid that stretches across tens of square kilometers, Evans told Live Science. The city is a place "that someone sat down and planned and elaborated on a massive scale on top of this mountain," he said. It "is not something that we necessarily would expect from this period."

Mahendraparvata dates back to around the late eighth to early ninth century, which is centuries before archeologists thought such organized cities emerged in the Angkor area. At that time, urban development was typically "organic," without much state-level control or central planning, he said.

What's more, the city-dwellers used a unique and intricate water-management system. "Instead of building this reservoir with urban walls, as they did for famous reservoirs at Angkor, they tried to carve this one out of the natural bedrock," Evans said. These ancient inhabitants carved an enormous basin out of stone but left it half-complete for unknown reasons.

The ambitious project's unseen scale and layout provide "a kind of prototype for projects of infrastructural development and water management that would later become very typical of the Khmer empire and Angkor in particular," Evans said.

Surprisingly, there's no evidence that this massive cistern was connected to an irrigation system. That likely means one of two things: The city was left incomplete before the residents could figure out how to provide water for agriculture, or the lack of irrigation is one reason the city was never finished.

Mahendraparvata is "not located at an especially advantageous place for rice agriculture," which could explain why the city wasn't the capital for long, Evans said. Rice was the dominant agricultural crop of the greater Angkor region at the time. The city, from which King Jayavarman II supposedly declared himself the king of all the Khmer kings, was a capital only between the late eighth to early ninth centuries, according to inscriptions found.

Though most archaeologists don't attribute great historical accuracy to these inscriptions, this particular story matches the dating and lidar data from the study, Evans said.

"Now, having a very complete picture of the whole, greater Angkor area and a finalized map of the whole thing, we can start to do some pretty sophisticated modeling of things like population and growth over time," Evans said.

He said he hopes that future research will tease apart what happened to this ancient city between its birth, when it was bustling with new ideas, and its demise, when it disappeared among the dense leaves.

In a series of articles published recently in the journal Antiquity, researchers describe their discoveries from Angkor Wat — a temple built in the 12th century that was dedicated to the god Vishnu. Later it was converted into a Buddhist temple.

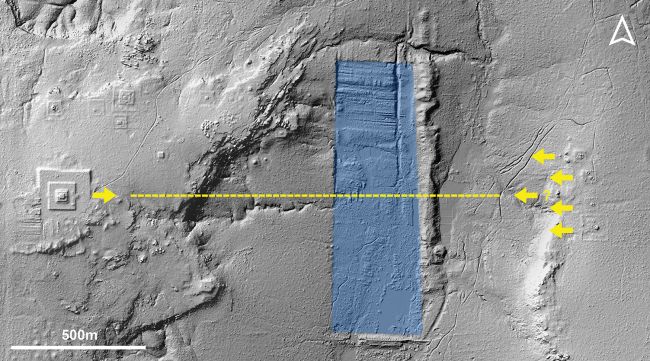

The new discoveries include a massive structure — almost a mile long — that contains rectispiral designs. The discoveries also include the remains of eight towers that may have been part of a shrine that was used while Angkor Wat was under construction.

The remains of the structure with the spiral design can be seen in this image. The image was taken using a laser-scanning technology known as LiDAR. It allows for structures to be detected beneath vegetation and modern development (which is highlighted in red).

The structure is made of sand, and is about 1,500 meters by 600 meters (about 1 mile by 1,970 feet) in size and its purpose is unknown. (Image courtesy Khmer Archaeology Lidar Consortium, KALC)

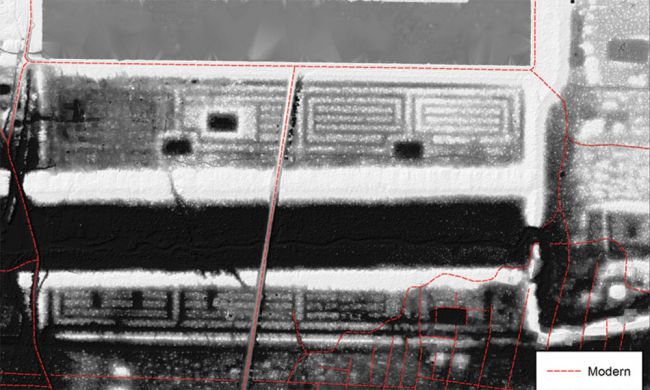

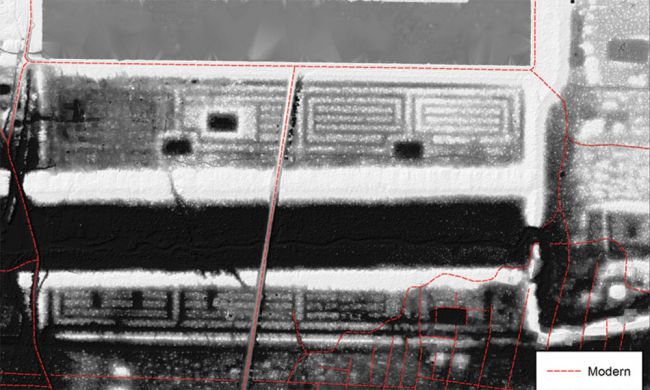

The LiDAR images have allowed archaeologists to detect new structures, including the remains of residences and pools used by those who serviced Angkor Wat. They've also detected remains from the wider city of Angkor. (Image courtesy Khmer Archaeology Lidar Consortium, KALC)

Archaeologists also reported in the journal Antiquity that they had discovered the remains of eight towers near the western gateway of Angkor Wat. The location of the tower remains can be seen in this image. Some of the towers appear to form square patterns and may have been used to support a shrine that was in use while Angkor Wat was being built. (Image by Till Sonnemann and image base courtesy of ETH Zurich)

The remains of the towers were discovered using a combination of ground-penetrating radar and excavation. This image shows ground-penetrating radar being conducted at Angkor Wat. (Image courtesy Till Sonnemann)

Excavation was used to study remains of the now buried towers. The towers appear to have been demolished sometime after construction on Angkor Wat's western gateway began. (Image courtesy Till Sonnemann)

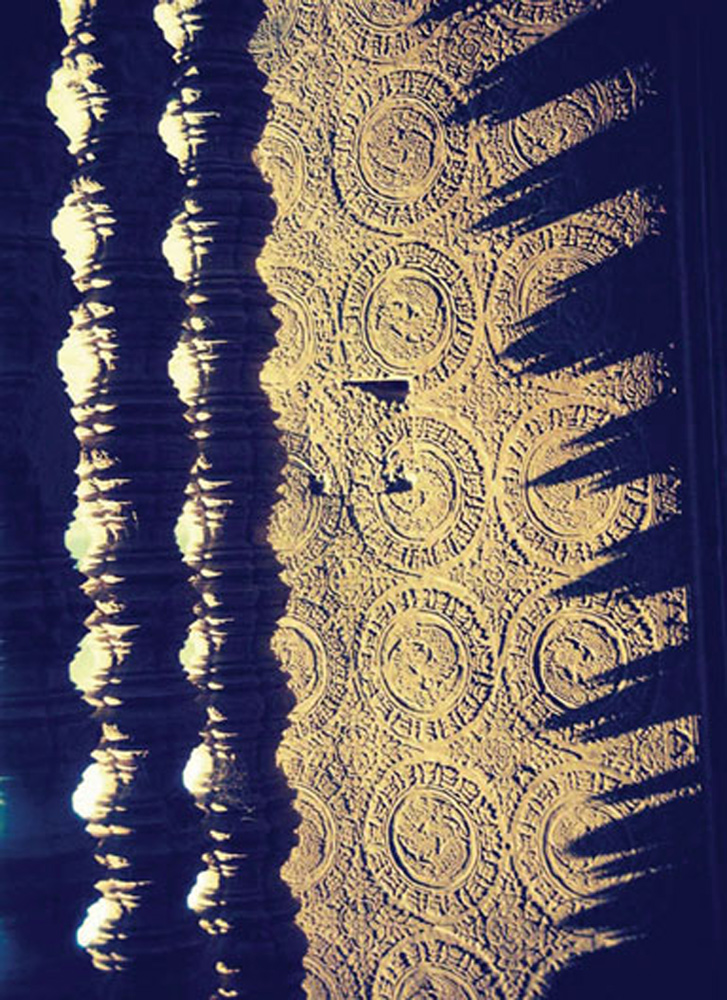

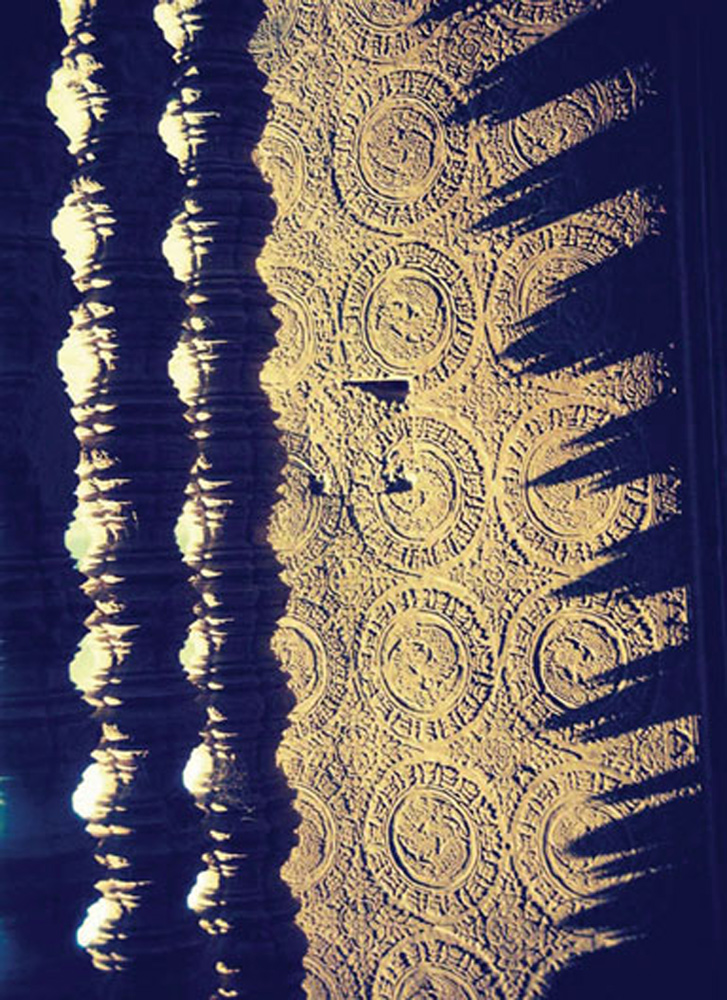

This image illustrates another interesting feature at Angkor Wat: Shadows in the shape of the central towers of Angkor Wat produced by the late-afternoon sun shining through carved pillars in the windows of the galleries. This effect was noted in an Antiquity article. (Image courtesy Christophe Pottier)

The study's findings were published on Oct. 15 in the journal Antiquity.