DepthReading

Silk For Paper: A Textile Hoard Found Near Jericho

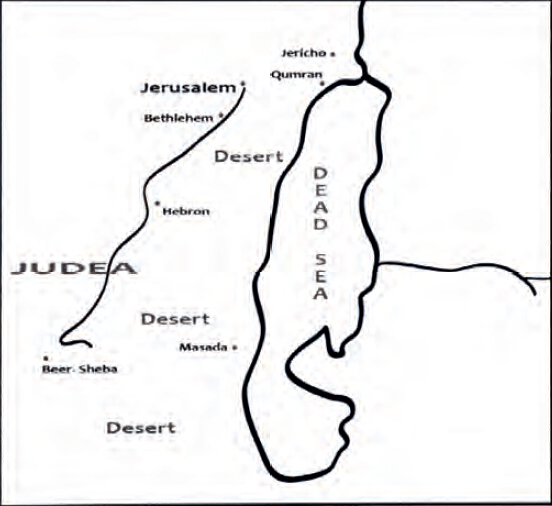

Silk has been discovered in the Land of Israel from sites dating to the Byzantine period and from the early Islamic

period onwards. The most important textile assemblage was discovered in a cave near Jericho (Qarantal Cave 38, see

right and map below) during excavations carried out in 1993 on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The cave

consists of several connected spaces and the textiles were discovered in only one of these, assumed to be a storage

area. Preserved by the arid climate of the Judean Desert, the768 textiles, 34 basketry fragments and 98 cordage fragments

discovered display a remarkable variety of materials and techniques, suggesting diverse geographical origins.

The original dating of the material based on their archaeological context to the early ninth to late thirteenth centuries

AD has since been confirmed by Carbon-14 analysis. Many developments in the early medieval period can be

observed by studying the textiles. Some of these took place in foreign regions — Persia, India, China and Europe. Others

were probably local but are thus far unique to this site, such as the combination of a linen warp and cotton weft.

474 textiles fragments have been analyzed and catalogued. An additional 285, too small or fragile to be cleaned or handled,

have been counted and defined by the material they are made from. Most significant are the silk fragments made

by various techniques, some of which required sophisticated looms. The textiles are torn, cut and patched, and many have

been reused, sometimes more than once. Many are composed of several different textiles or of several pieces of the same

material stitched together (see opposite). Others have been cut into rectangles, odd shapes or strips. All are small and

worn. Some were stained (with substances that could not be removed by the usual cleaning methods) and some were

partially burned. Some of the reused textiles are of high-quality material and design, only affordable by the elite. It can be assumed

that most of these were originally parts of clothing, such as tunics, although no complete garment is found. Others can

be recognized as bags, wrappers and strips for tying.

Materials, Techniques and Designs The largest group are made of cotton (285), with almost the same number of linens (261).

There are also 134 pieces with a linen warp and cotton weft and 5 pieces with a linen warp and a weft of both cotton and linen.

However, I shall concentrate here on the silks. Nine linen textiles are decorated with coloured silk tapestry bands of brown, beige,

gold, red, green, black, blue and yellow. The motifs of these bands show swimming birds (possibly ducks) and birds’ heads.

Others have linen tabby and silk tapestry depicting swimming birds and other unrecognizable motifs in the cartouche. Many such textiles originating in

Egypt have been dated to the tenth and eleventh centuries. The find also included one mulham (silk warp with hidden

cotton wefts). The silks show a loose Z-spun warp while the weft is | (floss). They are in various weaves including tabbies, 3:1

twill and a soumak. The eighteen pieces of compound weaves include double-faced compound tabbies (see opposite), weft

faced compound twills and lampas weaves. They have geometric, floral or interlaced patterns or show birds, animals or

remains of Arabic inscriptions. These are all luxury textiles woven on sophisticated looms such as the drawloom.

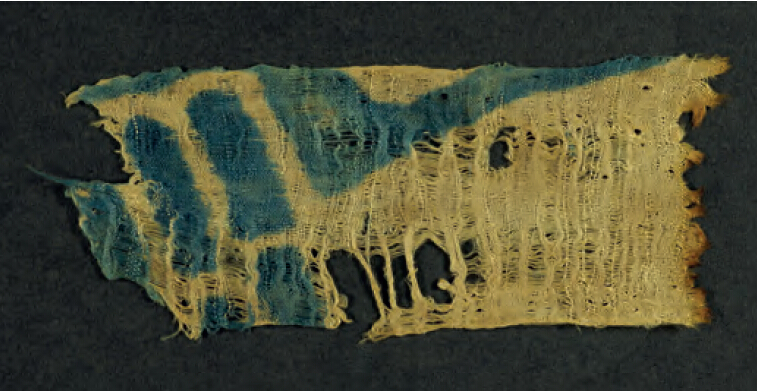

Unique to Cave 38 are two block-printed silk plain weave textiles with no twist of the fibres (example shown below).

Origin

The silk fragments were not produced locally as silk was not cultivated in the region. Nor were they likely to have been

imported from China based on the designs and spin direction. Compound-weave silks have been discovered in Egypt,

for example, at Antinoë (Geijer 1982). One piece discovered at ‘Avdat in Israel also originated from Egypt (Baginski and

Tidhar 1978). In the Byzantine period and after the Islamic conquest, textile centres in Syria were already producing

such textiles (King 1987; Otavski 1995): some have been preserved as relic-wrappers in the treasuries of European

churches (Muthesius 1997) and a few have been found in excavation near Rayy (Iran). The silks could therefore have been

imported from Syria, Byzantium, Mesopotamia or Persia.

Conclusions

Given that no other artefacts from this period, apart from a few ceramic shards, were found in this room of Cave 38 we

can assume it was not used as a dwelling. There is also no indication of spinning or weaving at the cave, or of textiles

repairs or tailoring. Why then were so many used textiles stored here? It can be hypothesized that the people who placed them there

were rag collectors or merchants who had collected them for the paper industry. Paper-making had been introduced

by the Arabs from China through Central Asia in the eighth century CE and became popular in the region. Linen, cotton,

and date-palm leaves and fibres were used as raw materials. The Arabs’ massive use of cotton for paper-making was a

feature of this industry, utilizing the waste products of the local cotton-based textiles industry (Amar, Gorski and Neumann

2010; Hunter 1978). Because of the unrest due to the frequent fighting between the local population and the various conquerors who

invaded the area in the tenth-thirteenth centuries, perhaps the merchants were unable to return to the cave to retrieve

their textiles. This idea, that this was a store of raw material for paper-making left by merchants, is supported by the

large number of textiles found in this one cave. This contrasts with the much smaller number of medieval textiles found in

other caves in the Judean desert.

Notes

This is a shortened version of a paper given by Orit Shamir at the conference in Hangzhou (see p. 4). A longer version has

previously been published in the Textile Society of America. Orit Shamir is Head of the Department of Museum and Exhibits

and Curator of Organic Materials, National Treasuries Department, Israel. She has researched and published widely on textiles. Her articles

are available at: https://antiquities.academia.edu/OritShamir Alisa Baginski is a retired senior lecturer of textile history. She

was the creator of the textile study collection at the Shenkar College of Textile Technology and Fashion at Ramat-Gan, Israel. She

has published widely on textiles, among others ‘Later Islamic and Medieval textiles from excavations of the Israel Antiquities Authority.’

Textile History 32.1 (2001) 81-92.

(Top) Fragment of five textiles from Cave 38 stitched together. the main

fragment is silk weft-faced compound tabby. The cartouche shows pairs

of birds facing each other, with a branch with leaves in between.

(Middle) Silk, weft-faced compound tabby with design of octagons

with stylized plants and geometric motifs.

(Bottom) Linen decorated with silk tapestry.

Photographs by Clara Amit and Tzila Sagiv,

courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: