Ground radar has been evolving for decades. Like its predecessors, Neubauer’s “geo-radar” sent pulses of electromagnetic waves through the earth that generated details about depth, shape and location. Unlike them, the high-resolution device covered about ten times as much surface area in the same amount of time, enabling researchers to speed up the search process significantly.

The resulting 3-D images laid bare a sprawling forum. “We had discovered the main building of the city quarter of Carnuntum’s military camp,” says Neubauer. A computer analysis revealed foundations, roads and sewers, even walls, stairs and floors, as well as a cityscape whose landmarks included shops, baths, a basilica, the tribunal, and a curia, the center of local government.

“The amount of detail was incredible,” Neubauer recalls. “You could see inscriptions, you could see the bases of statues in the great courtyard and the pillars inside rooms, and you could see whether floors were wood or stone—and if there had been central heating.” Three-dimensional virtual modeling allowed the team to reconstruct what the forum—all 99,458 square feet of it—might have looked like.

In the spring of 2011, another search of the Carnuntum underground was attempted by a team of archaeologists, geophysicists, soil scientists and techies from the latest iteration of Neubauer’s organization, LBI ArchPro, with its international partners. Enhancements to sensors had increased their speed, resolution and capabilities. Strides had been made in electromagnetic induction (EMI), a method by which magnetic fields are transmitted into soil to measure its electrical conductivity and magnetic susceptibility. At Carnuntum, the soundings told researchers whether the earth underneath had ever been heated, revealing the location of, say, bricks made by firing clay.

Neubauer had been intrigued by aerial shots of the amphitheater just beyond the walls of the civilian city. On the eastern side of the arena was the outline of buildings he now reckons were a kind of outdoor shopping mall. This plaza featured a bakery, shops, a food court, bars—pretty much everything except a J. Crew and a Chipotle.

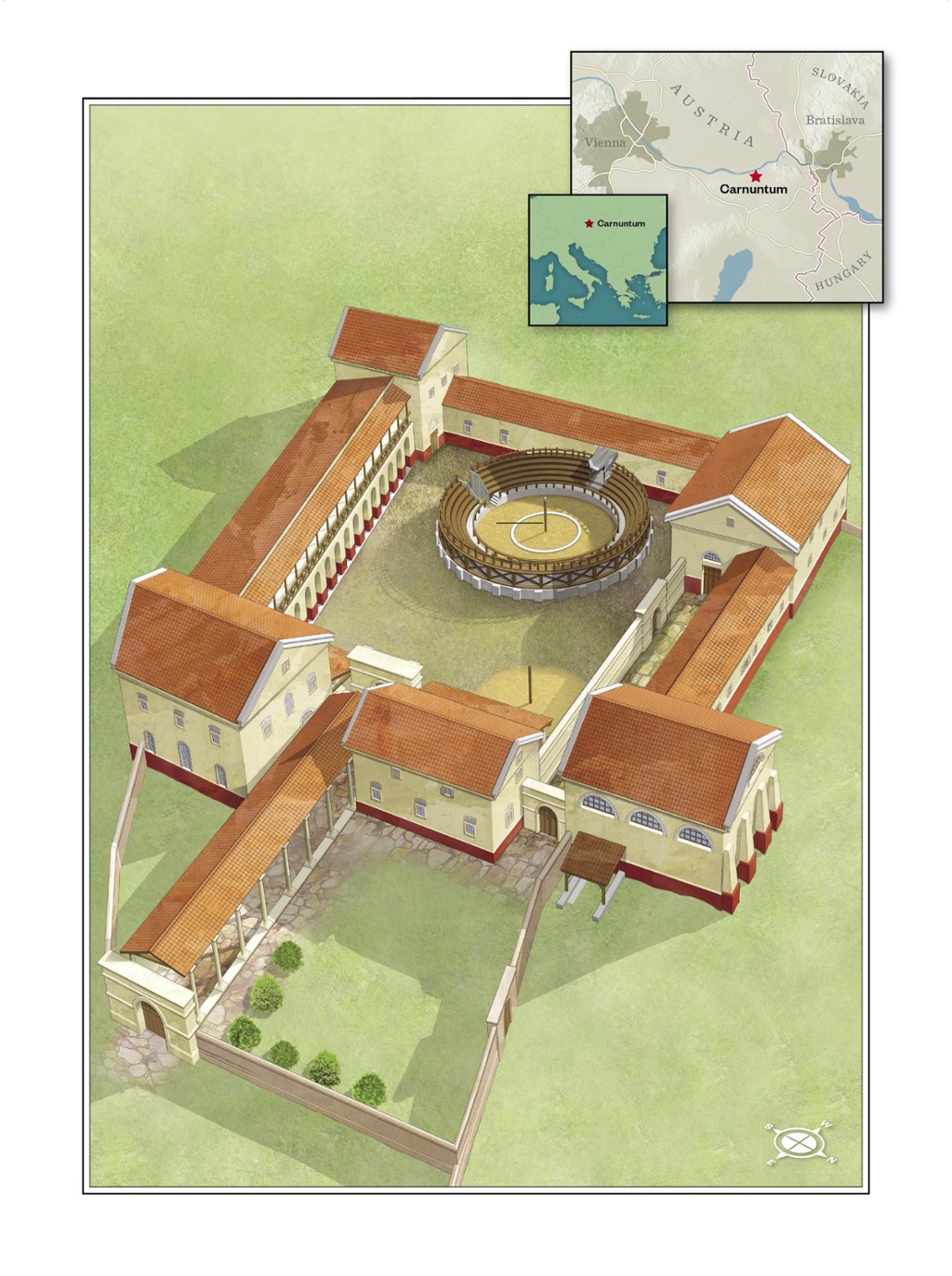

To the west of the amphitheater, amid groves of birches, oaks and white poplar, was a “white spot” that looked suspicious to Neubauer. Close inspection revealed traces of a closed quadrangle of edifices. “The contours were typical of a gladiator school,” Neubauer says.

The layout spanned 30,000 square feet and conformed to a marble fragment showing the Ludus Magnus, found in 1562 on one of the ancient slabs incised with Rome’s city plan. Fortunately for Neubauer’s team, the Romans tended to construct new settlements in Rome’s image. “Roman society built complex and very recognizable cityscapes with the global goal to realize outstanding symbolic and visual models of civitas and urbanitas,” says Maurizio Forte, a Duke University classics professor who has written widely on digital archaeology. “Civitas concerns the Roman view of ‘citizenship’ and ways to export worldwide the Roman civilization, society and culture. Urbanitas is how a city can fit the pattern of the Roman central power.”

From the empire’s rise in 27 B.C. until its fall in A.D. 476, the Romans erected 100 or so gladiator schools, all of which were intensely stylized and most of which have been destroyed or built over. Radar scans showed that, like the Ludus Magnus, the Carnuntum complex had two levels of colonnaded galleries that enclosed a courtyard. The central feature inside the courtyard was a free-standing circular structure, which the researchers interpreted as a training arena that would have been surrounded by wooden spectator stands set on stone foundations. Within the arena was a walled ring that may have held wild beasts. Galleries along the southern and western wings not designated as infirmaries, armories or administrative offices would have been set aside for barracks. Neubauer figures that about 75 gladiators could have lodged at the school. “Uncomfortably,” he says. The tiny (32-square-foot) sleeping cells were barely big enough to hold a man and his dreams, much less a bunkmate.

Neubauer deduced that other rooms—more spacious and perhaps with tiled floors—were living quarters for high-ranking gladiators, instructors or the school’s owner (lanista). A sunken cell, not far from the main entrance, seems to have been a brig for unruly fighters. The cramped chamber had no access to daylight and a ceiling so low that standing was impossible.

The school’s northern wing, the bathhouse, was centrally heated. During cold European winters—temperatures could fall to minus-13 degrees—the building was warmed by funneling heat from a wood-burning furnace through gaps in the floor and walls and then out roof openings. Archaeologists detected a chamber that they believe may have been a training room: they were able to see a hollow space, or hypocaust, under the floor, where heat was conducted to warm the paving stones underfoot. The bathhouse, with its thermal pools, was fitted with plumbing that conveyed hot and cold water. Looking at the bath complex, Neubauer says, “confirmed for the first time that gladiators could recover from harsh, demanding training in a fully equipped Roman bath.”

Marcus Aurelius was a philosopher-king who, despite the border battles raging during his administration, was inclined toward peace. The third book of his Meditations—philosophical conversations with himself in Greek—may have been written in Carnuntum’s main amphitheater, where circuses featured savage treatment of criminals. One could envision the emperor attending these brutal entertainments and turning aside to jot down his lofty thoughts. Generally, though, he was not a big fan of the mutual butchery of gladiators.

Nowadays, Marcus Aurelius is remembered less for his philosophizing than for being smothered by young Commodus at the start of the swords-and-sandals epic Gladiator. In reality, he succumbed to a devastating plague—most likely smallpox—that wiped out as many as ten million people across the empire. The film hewed closer to received history in its depiction of Commodus, an antisocial Darwinist whose idea of culture was to slaughter giraffes and elephants and take up crescent-headed arrows to shoot the heads off ostriches. True, he actually wasn’t stabbed to death in the ring by a hunky gladiator, but his demise was no less theatrical: Commodus’ dissolute reign was cut short in A.D. 192 when, after several botched assassination attempts, he was strangled in the bath by his personal trainer, a wrestler named Narcissus.

Commodus was a gladiator manqué who may have acquired his taste for the sport during a period in his youth (A.D. 171 to 173), some of which was misspent in Carnuntum. During the latest round of excavations, Neubauer concluded that the popularity of gladiating there necessitated two amphitheaters. “Nearly every other Roman outpost had a single arena,” he says. “In Carnuntum, one belonged to the military camp and served the legionnaires. The other, next to the school, belonged to the civil city and satisfied the desires of ordinary citizens.”

The gladiator era was a time of strict law and order, when a family outing consisted of scrambling for a seat in the bleachers to watch people be sliced apart. “The circuses were a brutal, disgusting activity,” says LBI ArchPro senior researcher Christian Gugl (“No relation to the search engine”). “But I suppose spectators enjoyed the blood, cruelty and violence for a lot of the same reasons we now tune in to ‘Game of Thrones.’”

Rome’s throne games gave the public a chance, regularly taken, to vent its anonymous derision when crops failed or emperors fell out of favor. Inside the ring, civilization confronted intractable nature. In Marcus Aurelius: A Life, biographer Frank McLynn proposed that the beastly spectacles “symbolized the triumph of order over chaos, culture over biology....Ultimately, gladiatorial games played the key consolatory role of all religion, since Rome triumphing over the barbarians could be read as an allegory of the triumph of immortality over death.”

Neubauer likens the school in Carnuntum to a penitentiary. Under the Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.), the “students” tended to be convicted criminals, prisoners of war or slaves bought solely for the purpose of gladiatorial combat by the lanista, who trained them to fight and then rented them out for shows—if they had the right qualities. Their ranks also included free men who volunteered as gladiators. Under the Empire (27 B.C. to A.D. 476), gladiators, while still made up of social outcasts, also included not only free men, but noblemen and even women who willingly risked their legal and social standing by taking part in the sport.

It’s doubtful that many fighters-in-training were killed at Carnuntum’s school. The gladiators represented a substantial investment for the lanista, who trained, housed and fed combatants, and then leased them out. Contrary to Hollywood mythmaking, slaying half the participants in any given match wouldn’t have been cost-effective. Ancient fight records suggest that while amateurs almost always died in the ring or were so badly maimed that waiting executioners finished them off with one merciful blow, around 90 percent of trained gladiators survived their fights.

The mock arena at the heart of the Carnuntum school was ringed by tiers of wooden seats and the terrace of the chief lanista. (A replica was recently built on the site of the original, an exercise in reconstruction archaeology deliberately limited to the use of tools and raw materials known to have existed during the Empire years.) In 2011, GPR detected the hole in the middle of the practice ring that secured a palus, the wooden post that recruits hacked at hour after hour. Until now it had been assumed that the palus was a thick log. But LBI ArchPro’s most recent survey indicated that the cavity at Carnuntum was only a few inches thick. “A thin post would not have been meant just for strength and stamina,” Neubauer argues. “Precision and technical finesse were equally important. To injure or kill an opponent, a gladiator had to land very accurate blows.”

Every fighter was a specialist with his own particular equipment. The murmillo was outfitted with a narrow sword, a tall, oblong shield and a crested helmet. He was often pitted against a thraex, who protected himself with sheathing covering the legs to the groin and broad-rimmed headgear, and brandished a small shield and a small, curved sword, or sica. The retiarius tried to snare his opponent in a net and spear his legs with a trident. In 2014, a traditional dig in Carnuntum’s ludus turned up a metal plate that probably came from the scale armor of a scissor, a type of gladiator sometimes paired with a retiarius. What distinguished the scissor was the hollow steel tube into which his forearm and fist fitted. The tube was capped: At the business end was a crescent-shaped blade meant to cut through the retiarius’ net in the event of entanglement.

One of the most surprising new finds was a chicken bone unearthed from where the grandstand would have been. Surprising, because in 2014 Austrian forensic anthropologists Fabian Kanz and Karl Grossschmidt established that gladiators were almost entirely vegetarians. They conducted tests on bones uncovered at a mass gladiator graveyard in Ephesus, Turkey, showing that the fighters’ diets consisted of barley and beans; the standard beverage was a concoction of vinegar and ash—the precursor of sports drinks. Neubauer’s educated guess: “The chicken bone corroborates that private displays were staged in the training arena, and rich spectators were provided with food during the fights.”

Outside the ludus walls, segregated from Carnuntum’s civilian cemetery, Team Neubauer turned up a burial field crammed with gravestones, sarcophagi and elaborate tombs. Neubauer is convinced that a gold-plated brooch unearthed during the chicken-bone dig belonged to a politician or prosperous merchant. “Or a celebrity,” he allows. “For instance, a famous gladiator who had died in the arena.” The man fascinated by the Hallstatt charnel house may have located a gladiator necropolis.

Top gladiators were folk heroes with nicknames, fan clubs and adoring groupies. The story goes that Annia Galeria Faustina, the wife of Marcus Aurelius, was smitten with a gladiator she saw on parade and took him as a lover. Soothsayers advised the cuckolded emperor that he should have the gladiator killed, and that Faustina should bathe in his blood and immediately lie down with her husband. If the never reliable Scriptores Historiae Augustae is to be believed, Commodus’ obsession with gladiators stemmed from the fact that the murdered gladiator was his real dad.

Following in the (rumored) tradition of the emperors Caligula, Hadrian and Lucius Verus—and to the contempt of the patrician elite—Commodus often competed in the arena. He once awarded himself a fee of a million sestertii (brass coins) for a performance, straining the Roman treasury.

According to Frank McLynn, Commodus performed “to enhance his claim to be able to conquer death, already implicit in his self-deification as the god Hercules.” Wrapped in lion skins and shouldering a club, the mad ruler would galumph around the ring à la Fred Flintstone. At one point, citizens who had lost a foot through accident or disease were tethered for Commodus to flog to death while he pretended they were giants. He chose for his opponents members of the audience who were given only wooden swords. Not surprisingly, he always won.

Enduring his wrath was only marginally less injurious to health than standing in the path of an oncoming chariot. On pain of death, knights and senators were compelled to watch Commodus do battle and to chant hymns to him. It’s a safe bet that if Commodus had enrolled in Carnuntum’s gladiator school, he would have graduated summa cum laude.

LBI ArchPro is housed in a nondescript building in a nondescript part of Vienna, 25 miles west of Carnuntum. Next to the parking lot is a shed that opens like Aladdin’s cave. Among the treasures are drones, a prop plane and what appears to be the love child of a lawn mower and a lunar rover. Rigged onto the back of the quad bikes (motorized quadricycles) is a battery of instruments—lasers, GPR, magnetometers, electromagnetic induction sensors.

Many of these gadgets are designed to be dragged across a field like futuristic farm equipment. “These devices allow us to identify structures several yards below ground,” says Gugl, the researcher. “The way the latest radar arrays can slice through soil is kind of Star Treky, though it lacks that Hollywood clarity.”

No terrain seems inaccessible to Neubauer’s explorers. Your eyes linger on a rubber raft suspended from the ceiling. You imagine the Indiana Jones-like possibilities. You ask, “Is the raft used for plumbing the depths of the Nile?”

“No, no, no,” Gugl protests. “We’re just letting some guy store it here.”

He leads you on a tour of the offices.

On the first floor, the common room is painted some institutional shade unknown to any spectrum. There’s an air of scruffiness in the occupants—jeans, T-shirts, running shoes; young researchers chat near a floor-to-ceiling photo of Carnuntum’s topography or gaze at animated video presentations, which track the development of the town in two and three dimensions.

**********

LBI ArchPro goes over one of the amphitheaters at Carnuntum with a motorized ground-penetrating radar array. (Reiner Riedler / Anzenberger Agency)

On a desktop monitor, a specialist in virtual archaeology, Juan Torrejón Valdelomar, and computer scientist Joachim Brandtner boot up a 3-D animation of LBI ArchPro’s surprising new discovery at Carnuntum—the real purpose of the Heidentor. Built in the fourth century during the reign of Emperor Constantius II, the solitary relic was originally 66 feet high, comprising four pillars and a cross vault. During the Middle Ages, it was thought to be a pagan giant’s tomb. Ancient sources indicate that Constantius II had it erected in tribute to his military triumphs.

But a radar scan of the area provides evidence that the Heidentor was surrounded by bivouacs of legionnaires, soldiers massed by the tens of thousands. Like a time-lapse cartoon of a flower unfolding, the LBI ArchPro graphic shows Roman campsites slowly shooting up around the memorial. “This monumental arch,” says Neubauer, “towered above the soldiers, always reminding them of their allegiance to Rome.”

Now that LBI ArchPro has digitally leveled the playing field, what’s next at Carnuntum? “Primarily, we hope to find building structures that we can clearly interpret and date,” says archaeologist Eduard Pollhammer. “We don’t expect chariots, wild animal cages or remains inside the school.”

Within another walled compound that adjoins the ludus is an extended open campus that may contain all of the above. Years ago a dig inside a Carnuntum amphitheater turned up the carcasses of bears and lions.

The ongoing reconstructions have convinced Neubauer that his team has solved some of the city’s enduring mysteries. At the least, they show how the march of technology is increasingly rewriting history. It’s been said the farther backward you look, the farther forward you are likely to see. In Book VII of his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius put it another way: “Look back over the past, with its changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the future, too.”