DepthReading

Why archaeology needs to come out of the cave and into the digital age

The explosion of DNA studies as it has become cheaper and easier has led to a seismic shift: a whole new class of questions are possible, that stone tools, no matter what new analytical techniques we invent, could never answer. We can now discern multiple phases of dispersal from Africa, probably beginning two million years ago. Population diversification and interaction was taking place throughout the Old World, over a colossal amount of time, with local trajectories leading to Neanderthals in Europe, Homo sapiens in Africa, yet others in Asia, all at the same time.

It’s dizzying stuff, and that’s before we take into account our own species’ scenic route: over the last 1500 centuries humans like us spread across mountain ranges, deserts and even seas, reaching the furthest stretches of the Old World between 55-50,000 years ago. But these were not empty lands; all those pre-existing archaic populations were still there. In China a “mystery” species shared the landscape with the first Homo sapiens migrants between 120-80 Ka, while the first Australians have met the diminutive H. floresiensis en-route in Indonesia. And the old debates about Neanderthals and us may need to be reversed: their dominance might have prevented Homo sapiens entering Europe until after 50,000 years ago.

Ancient genetics effectively provides a new wavelength of data, allowing us to scrutinise previously invisible details of those 5-6000 generations. Two cases illustrate the jaw-dropping impact this technique has had. Over the past six years Denisova cave, Altai, has repeatedly produced amazing findings: not only didNeanderthals and Homo sapiens live here at different times during a 100,000 year window, but a third population with deep non-African roots also existed.Identified purely through DNA analysis of bone fragments and teeth, we have no idea what these people looked like or exactly what their culture was. Yet these populations cannot have been truly alien to each other as genetics shows three-way interbreeding between Denisovans, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, atdifferent times and in differing amounts.

Just last year another astonishing result came out. We already knew that Neanderthals were ancestral to some modern populations, but in 2015 one of a number of hybrid-looking fossils from eastern Europe was genetically tested. That individual had a Neanderthal ancestor within just a few generations, an extremely unlikely result if interbreeding had been a rare occurrence.

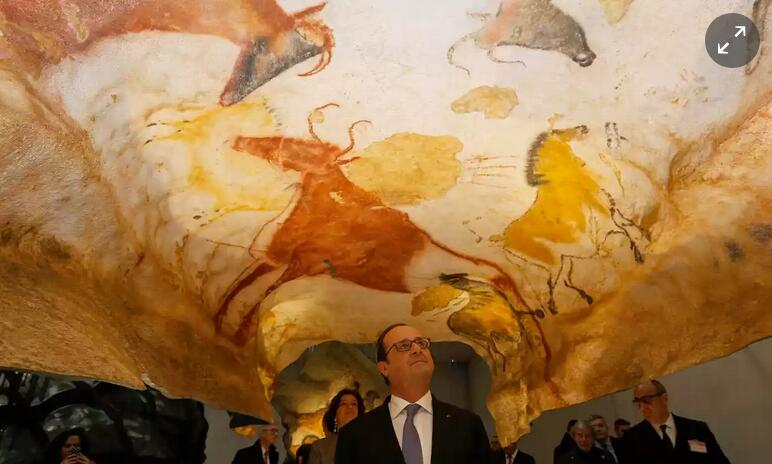

Politics and prehistory: it’s time that discoveries about our remote past came out of the shadows on the cave wall. Photograph: Regis Duvignau/AFP/Getty Images

It’s nearly end-of-year “listicle” season, and 2016 has offered plenty of fascinating archaeological discoveries - my favourite is the Neanderthal-made stalagmite construction, which truly deserves the epithet “mysterious”. But let’s look beyond the past 12 months for a tale of hope amidst fear: the most important human origins discovery of the past three decades, and why it matters now more than ever.

Test-tubes, not trowels, have provided the greatest advances in prehistoric research in the past 30 years. The “Oldest X”, or “Earliest Y” isn’t our most important discovery, instead it’s the profound connectedness of humanity we’ve discovered through genetics. Everyone alive today is deeply and closely related:we are more similar to each other than two groups of chimpanzees separated only by a river. Even more important, most of our differences in genetic terms are found within populations, not between them.

As our ability to analyse DNA becomes more nuanced, we’re assembling an increasingly high resolution map of multiple interactions across time and space. The remnant archaic DNA in living people of just a few percent sounds tiny, but it represents thousands of individual unions, and children raised, rather than a few chance encounters.

Yet this fascinating record of unity is not helping people today to feel or act inclusively. A couple of weeks ago, following a bizarre tweet, I ended up down a rabbit-hole of modern white supremacist propaganda. Amidst a morass of racism, homophobia and paranoia, prehistory and human origins were repeatedly referred to. Just one example is the use of the so-called Solutrean hypothesis to claim that America was first colonised by a European culture. This theory is genuinely debated by archaeologists, but it certainly does not support white supremacy.

The murky far right twists a broad range of modern archaeology for its propaganda. A few weeks ago, young men giving Nazi salutes in Washington DC were claiming that evidence of cultural adaptations to different environments proves racist evolutionary theories. British far right groups are no different, claiming that the “British race” goes back to the Palaeolithic.

But racial “purity” has never been part of our story. 21st century genetics has unveiled a fractal landscape, where at every scale we find both diversity and relatedness. Stone tools are the collective dust of generations, but ancient DNA tunes us into the songs of families and individuals as well as the chorus of populations.

It’s easy for researchers to keep their studies aloof from the messy, wider world. But when we increasingly have to justify our funding, archaeologists need to step up and show that discoveries about our remote past are vital in steering our future course. Despite paranoid far right claims about academia censoring history, andfears of a “post fact” era driving online radicalisation, the existence of curiosity about, rather than indifference to, our past offers a way to open minds. If we hold our own expertise in any regard, this goes beyond outreach or science communication. We have a duty to amplify the research we dedicate our lives to, and ensure there is more real information than fake facts.

Our deep history as a species has a lot in common with us as individuals: it’s scattered with innovations that fluoresced and faded like supernovas, accidental explorations that trail-blazed then backtracked across entire continents, and myriad couplings under night skies. It’s time that prehistory came out of the shadows on the cave wall, and reclaims our global heritage as one that emphasises unifying love and trust over divisive fear and hate.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: