DepthReading

This 3,500-Year-Old Greek Tomb Upended What We Thought We Knew About the Roots of Western Civilization

The recent discovery of the grave of an ancient soldier is challenging accepted wisdom among archaeologists

Davis and Stocker disagree on where they were when they received Dibble’s call from the dig site. Stocker remembers they were at the team’s workshop. Davis thinks they were at the local museum. Dibble recalls that they were in line at the bank. Whichever it was, they rushed to the site and, Stocker says, “basically never left.”

That first splash of green became an ocean, filled with layer after layer of bronze, reminiscent of Schliemann’s magnificent finds. “It was surreal,” says Dibble. “I felt like I was in the 19th century.”

The researchers celebrated the next day with a lunch of gourounopoulo (roast suckling pig) from the local farmer’s market, eaten under the olive trees. For Davis and Stocker, the challenge of the find soon set in. “Everything was interlocked, crushed with everything else,” says Davis. “We never imagined that we might find anything more than a few potsherds that could be put together with glue. Suddenly, we were faced with this huge mess.” The collaborators began working 15-hour shifts, hoping to clear the site as quickly as possible. But after two weeks, everyone was exhausted. “It became clear that we couldn’t continue at that pace, and we weren’t going to finish,” Stocker says. “There was too much stuff.”

About a week in, Davis was excavating behind the stone slab. “I’ve found gold,” he said calmly. Stocker thought he was teasing, but he turned around with a golden bead in his palm. It was the first in a flood of small, precious items: beads; a tiny gold birdcage pendant; intricately carved gold rings; and several gold and silver cups. “Then things changed,” says Stocker. Aware of the high risk of looting, she organized round-the-clock security, and, apart from the Ministry of Culture and the site’s head guard, the archaeologists agreed to tell no one about the more valuable finds. They excavated in pairs, always with one person on watch, ready to cover precious items if someone approached.

The largest ring discovered was made of multiple finely soldered gold sheets. (University of Cincinnati)

And yet it was impossible not to feel elated, too. “There were days when 150 beads were coming out—gold, amethyst, carnelian,” says Davis. “There were days when there was one seal stone after another, with beautiful images. It was like, Oh my god, what will come next?!” Beyond the pure thrill of uncovering such exquisite items, the researchers knew that the complex finds represented an unprecedented opportunity to piece together this moment in history, promising insights into everything from religious iconography to local manufacturing techniques. The discovery of a golden cup, as lovely as the day it was made, proved an emotional moment. “How could you not be moved?” says Stocker. “It’s the passion of looking at a beautiful piece of art or listening to a piece of music. There’s a human element. If you forget that, it becomes an exercise in removing things from the ground.”

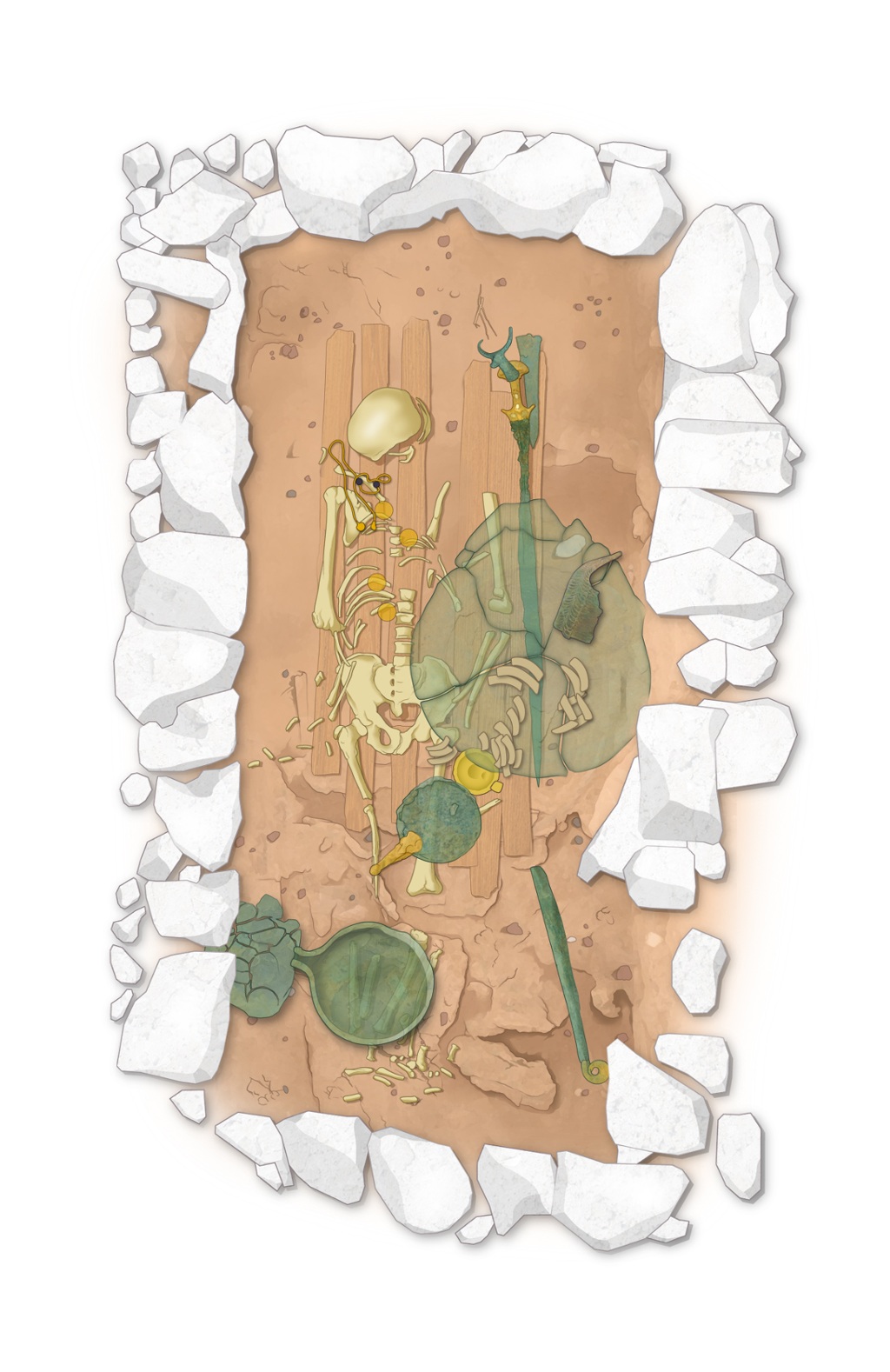

In late June 2015, the scheduled end to their season came and went, and a skeleton began to emerge—a man in his early 30s, his skull flattened and broken and a silver bowl on his chest. The researchers nicknamed him the “griffin warrior” after a griffin-decorated ivory plaque they found between his legs. Stocker got used to working alongside him in that cramped space, day after day in the blazing summer sun. “I felt really close to this guy, whoever he was,” she says. “This was a person and these were his things. I talked to him: ‘Mr. Griffin, help me to be careful.’”

In August, Stocker ended up in the local medical clinic with heatstroke. In September, she was rewarded with a gold-and-agate necklace that the archaeologists had spent four months trying to liberate from the earth. The warrior’s skull and pelvis were among the last items to be removed, lifted out in large blocks of soil. By November, the grave was finally empty. Every gram of soil had been dissolved in water and passed through a sieve, and the three-dimensional location of every last bead photographed and recorded.

Seven months later, Stocker sails through a low, green metal door into the basement of the archaeological museum in the small town of Chora, a few minutes’ drive from the palace. Inside, the room is packed with white tables, wooden drawers, and countless shelves of skulls and pots: the results of decades of excavations in this region.

Still the organizational force behind the Pylos project, Stocker looks after not just the human members of the team but a troupe of adopted animals, including the mascot, a sleek gray cat named Nestor, which she rescued from the middle of the road when he was 4 weeks old. “He was teeny,” she recalls. “One day he blew off the table.”

She’s also in charge of conservation. Around her, plastic boxes of all sizes are piled high, full of artifacts from the warrior’s grave. She opens box after box to show their contents—one holds hundreds of individually labeled plastic bags, each containing a single bead. Another yields seal stones carved with intricate designs: three reclining bulls; a griffin with outstretched wings. “I still can’t believe I’m actually touching them,” she says. “Most people only see things like this through glass in a museum.”

There are delicate ivory combs, thin bands of bronze (the remains of the warrior’s armor) and boar tusks likely from his helmet. From separate wrappings of acid-free paper she reveals a bronze dagger, a knife with a large, square blade (perhaps used for sacrifices) and a great bronze sword, its hilt decorated with thousands of minute fragments of gold. “It’s truly amazing, and in bad shape,” she says. “It’s one of our highest priorities.”

There are more than 1,500 objects in all, and although the most precious items aren’t here (they are under lock-and-key elsewhere), the scale of the task she faces to preserve and publish these objects is nearly overwhelming. She surveys the room: a life’s work mapped out before her.

“The way they dug this grave is just remarkable,” says Thomas Brogan, the director of the Institute for Aegean Prehistory Study Center for East Crete. “I think the sky’s the limit in terms of what we are going to learn.”

**********

Fragments of Ancient Life

From jewelry to gilded weapons, a sampling of the buried artifacts researchers are using to fill in the details about the social currents in Greece at the time the griffin warrior lived

By 5W Infographics; Research by Virginia Mohler

Like any momentous archaeological find, the griffin warrior’s grave has two stories to tell. One is the individual story of this man—who he was, when he lived, what role he played in local events. The other story is broader—what he tells us about the larger world and the crucial shifts in power taking place at that moment in history.

Analyses of the skeleton show that this 30-something dignitary stood around five-and-a-half feet, tall for a man of his time. Combs found in the grave imply that he had long hair. And a recent computerized facial reconstruction based on the warrior’s skull, created by Lynne Schepartz and Tobias Houlton, physical anthropologists at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, shows a broad, determined face with close-set eyes and a prominent jaw. Davis and Stocker are also planning DNA tests and isotope analyses that they hope will provide information about his ethnic and geographic origins.

At first, the researchers struggled to precisely date his burial. Soil layers are usually dated based on the shifting styles of ceramics; this grave held no pottery at all. But excavations of the grave’s surrounding soil in the summer of 2016 turned up pottery sherds that point to an archaeological period roughly corresponding to 1500-1450 B.C. So the warrior lived at the very end of the shaft grave period, just before construction of the Mycenaean palaces, including Nestor’s.

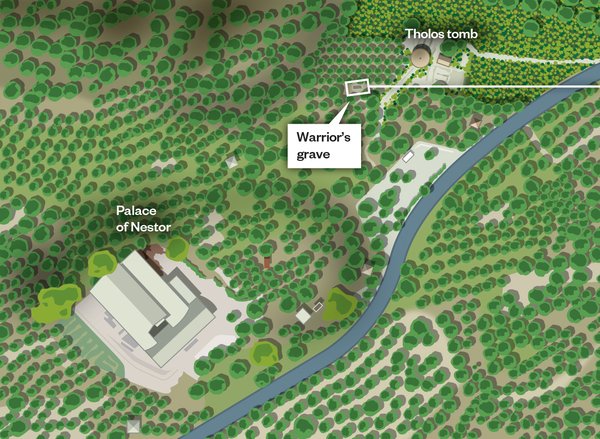

Davis and Stocker believe that the tholos tomb at Pylos was still in use at this time. If the warrior was in fact an important figure, perhaps even a leader, why was he buried in a separate shaft grave, and not in the tholos? Stocker wonders whether digging the shaft grave may say something about the manner of the warrior’s death—that it was unexpected—and proved a quicker option than deconstructing and rebuilding the entrance to the tholos. Bennet, on the other hand, speculates that contrasting burial practices in such close proximity may represent separate local family groups vying for supremacy. “It’s part of a power play,” he says. “We have people competing with each other for display.” To him, competition to amass exotic materials and knowledge may have been what drove the social development of Mycenaean ruling elites.

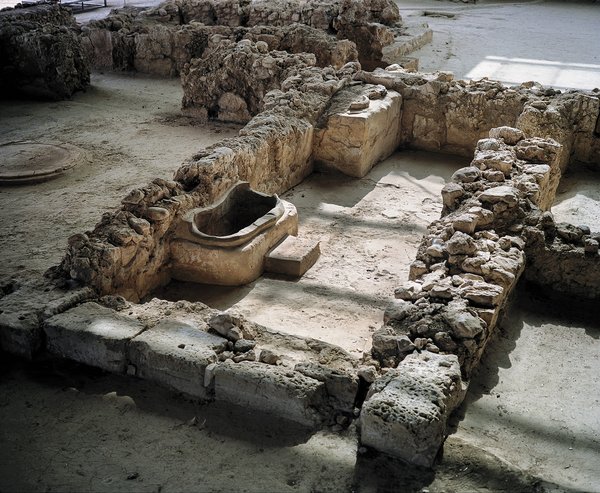

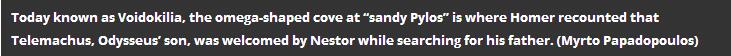

Within a few years of the warrior’s burial, the tholos went out of use, the gateway in the fortification wall closed, and every building on the hilltop was destroyed to make way for the new palace. On Crete, Minoan palaces across the island burned along with many villas and towns, although precisely why they did remains unknown. Only the main center of Knossos was restored for posterity, but with its art, architecture and even tombs adopting a more mainland style. Its scribes switched from Linear A to Linear B, using the alphabet to write not the language of the Minoans, but Mycenaean Greek. It’s a crucial transition that archaeologists are desperate to understand, says Brogan. “What brings about the collapse of the Minoans, and at the same time what causes the emergence of the Mycenaean palace civilization?”

The distinctions between the two societies are clear enough, quite apart from the fundamental difference in their languages. The Mycenaeans organized their towns with free-standing houses rather than the conglomerated shared buildings seen on Crete, for example. But the relationship between the peoples has long been a contentious subject. In 1900, just 24 years after Schliemann announced he’d found Homer’s heroes at Mycenae, the British archaeologist Arthur Evans discovered the Minoan civilization (named for Crete’s mythic King Minos) when he unearthed Knossos. Evans and subsequent scholars argued that the Minoans, and not the Mycenaean mainlanders, were the “first” Greeks—“the first link in the European chain,” according to the historian Will Durant. Schliemann’s graves, the thinking went, belonged to wealthy rulers of Minoan colonies established on the mainland.

In 1950, however, scholars finally deciphered Linear B tablets from Knossos and Pylos and showed the writing to be the earliest known form of Greek. Opinion now swung the other way: The Mycenaeans were reinstated as the first Greeks, and Minoan objects found in mainland graves were reinterpreted as status symbols stolen or imported from the island. “It’s like the Romans copying Greek statues and carting them off from Greece to put in their villas,” says Shelmerdine.

And this has been the scholarly consensus ever since: The Mycenaeans, now thought to have sacked Knossos at around the time they built their mainland palaces and established their language and administrative system on Crete, were the true ancestors of Europe.

The griffin warrior’s grave at Pylos offers a radical new perspective on the relationship between the two societies and thus on Europe’s cultural origins. As in previously discovered shaft graves, the objects themselves are a cross-cultural mix. For instance, the boar tusk helmet is typically Mycenaean, but the gold rings, which are rich with Minoan religious imagery and are on their own a hugely significant find for scholars, says Davis, reflect artifacts previously found on Crete.

Unlike ancient graves at Mycenae and elsewhere, however, which held artifacts from different individuals and time periods, the Pylos grave is an undisturbed single burial. Everything in it belonged to one person, and archaeologists can see precisely how the grave goods were positioned.

Significantly, weapons had been placed on the left side of the warrior’s body while rings and seal stones were on the right, suggesting that they were arranged with intent, not simply thrown in. The representational artwork featured on the rings also had direct connections to actual buried objects. “One of the gold rings has a goddess standing on top of a mountain with a staff that seems to be crowned by a horned bull’s head,” says Davis. “We found a bull’s head staff in the grave.” Another ring shows a goddess sitting on a throne, looking at herself in the mirror. “We have a mirror.” Davis and Stocker do not believe that all this is a coincidence. “We think that objects were chosen to interact with the iconography of the rings.”

Horns, which symbolize authority, appear on this bronze bull’s head and three gold rings. (University of Cincinnati)

In their view, the arrangement of objects in the grave provides the first real evidence that the mainland elite were experts in Minoan ideas and customs, who understood very well the symbolic meaning of the products they acquired. “The grave shows these are not just knuckle-scraping, Neanderthal Mycenaeans who were completely bowled over by the very existence of Minoan culture,” says Bennet. “They know what these objects are.”

New discoveries made by Davis and Stocker just this past summer provide more striking evidence that the two cultures had more in common than scholars have realized. Among the finds are remnants from what are likely the oldest wall paintings ever found on the Greek mainland. The fragments, which measure between roughly one and eight centimeters across and may date as far back as the 17th century B.C., were found beneath the ruins of Nestor’s Palace. The researchers speculate that the paintings once covered the walls of mansion houses on the site before the palace was built. Presumably, the griffin warrior lived in one of those mansions.

Moreover, small sections of pieced-together fragments indicate that many of the paintings were Minoan in character, showing nature scenes, flowering papyri and at least one miniature flying duck, according to Emily Egan, an expert in eastern Mediterranean art at the University of Maryland at College Park who worked on the excavations and is helping to interpret the finds. That suggests, she says, a “very strong connection with Crete.”

Together, the grave goods and the wall paintings present a remarkable case that the first wave of Mycenaean elite embraced Minoan culture, from its religious symbols to its domestic décor. “At the very beginning, the people who are going to become the Mycenaean kings, the Homeric kings, are sophisticated, powerful, rich and aware of something beyond the world that they are emerging from,” says Shelmerdine.

This has led Davis and Stocker to favor the idea that the two cultures became entwined at a very early stage. It’s a conclusion that fits recent suggestions that regime change on Crete around the time the mainland palaces went up, which traditionally corresponds to the decline of Minoan civilization, may not have resulted from the aggressive invasion that historians have assumed. The later period on Knossos might represent something more like “an EU in the Aegean,” says Bennet, of the British School at Athens. Minoans and Mycenaean Greeks would surely have spoken each other’s languages, may have intermarried and likely adopted and refashioned one another’s customs. And they may not have seen themselves with the rigid identities we moderns have tended to impose on them.

In other words, it isn’t the Mycenaeans or the Minoans to whom we can trace our cultural heritage since 1450 B.C., but rather a blending of the two.

The fruits of that intermingling may have shaped the culture of classical Greece and beyond. In Greek mythology, for example, the legendary birthplace of Zeus is said to be a cave in the Dicte mountains on Crete, which may derive from a story about a local deity worshiped at Knossos. And several scholars have argued that the very notion of a Mycenaean king, known as a wanax, was inherited from Crete. Whereas the Near East featured autocratic kings—the Egyptian pharaoh, for example, whose supposed divine nature set him apart from earthly citizens—the wanax, says Davis, was the “highest-ranking member of a ranked society,” and different regions were served by different leaders. It’s possible, Davis proposes, that the transfer to Greek culture of this more diffuse, egalitarian model of authority was of fundamental importance for the development of representative government in Athens a thousand years later. “Way back in the Bronze Age,” he says, “maybe we’re already seeing the seeds of a system which ultimately allows for the emergence of democracies.”

The revelation is compelling for anyone with an interest in how great civilizations are born—and what makes them “great.” And with rising nationalism and xenophobia in parts of Europe and the United States, Davis and others suggest that the grave contains a more urgent lesson. Greek culture, Davis says, “is not something that has been genetically transmitted from generation to generation since the dawn of time.” From the very earliest moments of Western civilization, he says, Mycenaeans “were capable of embracing many different traditions.”

“I think we should all care about that,” says Shelmerdine. “It resonates today, when you have factions that want to throw everybody out [of their countries]. I don’t think the Mycenaeans would have gotten anywhere if they hadn’t been able to reach beyond their shores.”

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: