DepthReading

St Cuthbert's coffin features in new display at Durham Cathedral

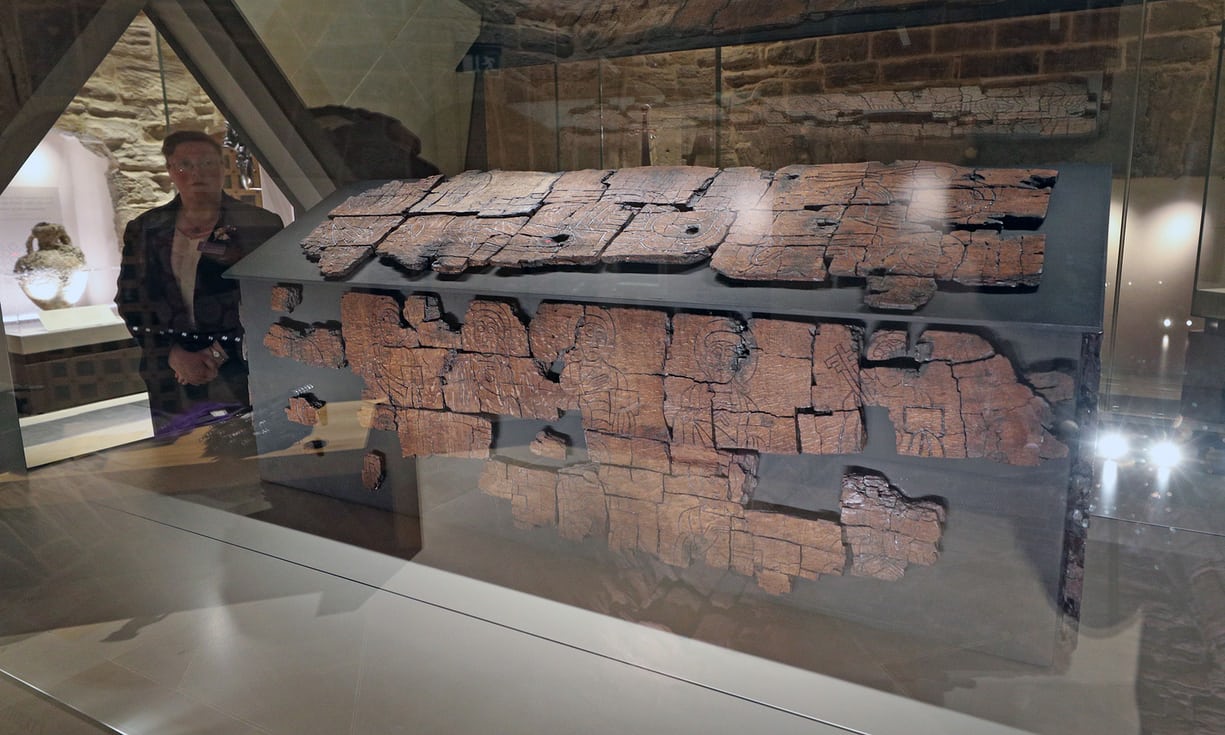

As the light picked out every detail of the angels and saints, and the runic and Latin inscriptions carved into the oak coffin of a man who died more than 1,300 years ago, the dean of Durham Cathedral struggled to find an appropriately reverent word. “Wow,” Andrew Tremlett finally said. “Wow.”

Janina Ramirez, a historian, was also seeing for the first time the cathedral’s new display of the coffin of St Cuthbert. She said she had been unable to sleep from excitement the night before. “This is the Tutankhamun’s tomb of the north-east,” she said, “a window into a time in history which some people call the dark ages.”

The coffin, made from English oak on Lindisfarne in 698 – 11 years after Cuthbert’s death – is regarded as the most important wooden object surviving in England from before the Norman conquest.

It is displayed surrounded by objects found in the coffin, which historians and archaeologists agree almost certainly did belong to the saint. They include his portable altar, a gold and garnet pectoral cross damaged and crudely repaired in his lifetime – which was found tucked into his robes in the 19th century – and most intimate of all, a rather scruffy ivory comb.

Marie-Therese Mayne, curator of the exhibition, regards the comb – made from African elephant ivory – as the clincher. “It’s just a comb, not even a very nice comb. There couldn’t be a more banal object. There was absolutely no reason for the monks to have kept it in the coffin unless they knew it really did belong to Cuthbert.”

The coffin was made when Cuthbert’s body was exhumed 11 years after his death in 687, possibly of tuberculosis and probably aged only 53. Mayne says despite the elegance of the incised figures, the coffin was just a roughly constructed wooden box. She thinks the monks had probably prepared a small reliquary for the bones and instead were shocked to find Cuthbert’s body still completely intact – taken as a sign of sanctity – and so had to quickly make a new full-sized coffin.

There was more drama in the centuries following Cuthbert’s death than in the lifetime of the modest, pious man, who had to be coaxed back from a remote hermit’s cell to become a bishop.

He did not rest in peace. When the monks fled inland to escape Viking raids, they took their treasures with them, including his body and his possessions. In 995, after wandering for a century, they settled in Durham where his shrine became a major pilgrimage site.

In 1104, his coffin was opened again –some of the contents including the tiny gospel now in the British Library removed – and his remains moved to a grander shrine behind the altar of the new cathedral. Mayne said the cathedral archives recorded that when important visitors were expected, the coffin was regularly opened, and one Alfred Westou, keeper of the shrine, used the comb to tidy up Cuthbert’s hair and beard.

The shrine was destroyed in the dissolution, but unusually Cuthbert’s relics were left to be disturbed again in the 19th century when the wooden coffin was removed. His body was then described as just bones with some skin and ligaments attached. It was reburied for the last time, in an elaborate new coffin, in 1899.

The treasures, previously on display in the cathedral’s undercroft, have been in storage for the past six years. The new exhibition spaces were created in the complex of medieval buildings: a £10m Heritage Lottery grant-aided project that has opened up spaces including the monks’ dormitory and the beautiful 14th-century stone-vaulted great kitchen. The kitchen, like the saint, survived the dissolution of the monasteries, and was still the main food preparation area for cathedral staff until the 1940s.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: