DepthReading

Where goddesses loved and fought

Spectacular archaeological sites provide a front-row seat to a mythological blockbuster

Around the 11th or 12th century BC a war was fought in western Anatolia in what today is Turkey. And it was fought not only between men, but also between gods and goddesses whose "immortal rage" - as Homer, the legendary author of the Iliad, put it - could not be thwarted.

That war was the Trojan War, talked of in many works of Greek literature, and most notably in the Iliad. It was waged against the city of Troy by the Grecian coalition after Paris, a Trojan prince, took Helen, daughter of Zeus, from her husband and king of Sparta Menelaus. (Sparta was a Greek city-state.)

Historians are at odds as to whether the Trojan War, depicted with as many twists and as much drama as it could possibly command, really happened. Yet for those whose answer is yes, the Turkish land, with the Aegean Sea to its west, is the place to be to try to imagine the fury of the immortals and the pride of the mortals, both powerful enough to send ships and tear down cities.

Today the mortals have long perished, while the once powerful presence of the immortals is still felt across Turkey, through what remains of the ancient cities where they were once worshipped.

Topping that list is Ephesus, built by Greek colonists in the 10th century BC and located near the modern town of Selcuk, in the southwest of present-day Turkey. The city, a UNESCO World Heritage site and Asia Minor's largest Greco-Roman city, has long been famed for the Temple of Artemis, which in turn was completed around 550 BC.

Little remains of the temple site today. The grandest heritage of Ephesus, which is also a reminder of its golden days under the control of the Roman Republic, is the Library of Celsus. However, in the on-site Ephesus Museum, two large marble statues of Artemis stand facing each other, both created around the first century AD. In both cases, Artemis was rendered with multiple breasts - a distinct feature befitting her unique role as the "Great Mother Goddess". (Others believe that the spherical objects covering the lower part of her chest are not female breasts, but the testicles of a bull, an animal that has appeared in large numbers as her hair and robe decorations.)

The goddess, in charge of hunting, wilderness, childbirth and virginity, was presented as a strong supporter of Troy throughout the war. As Greeks sailed across the Aegean Sea to Troy, Artemis becalmed the wind and stopped their journey. In the Iliad, she came to blows with Hera, queen of all gods, when the divine allies of the Greeks and Trojans came to confront one another.

This is mainly because her brother Apollo was the patron god of Troy and she herself was widely worshipped in western Anatolia in historical times. But there may also be other reasons, like her hatred toward Hera.

According to Greek mythology, Artemis was the daughter of Zeus and Leto, who was hounded throughout her pregnancy by Zeus' perennially jealous and vengeful wife Hera. Upon Artemis' own delivery, she assisted her poor mother with the birth of her younger twin-brother Apollo. (Artemis herself prefers to remain a maiden and is sworn never to marry.)

According to the Iliad, Artemis, after being struck by Hera during their conflict, fled crying to her father Zeus: "It was your wife Hera, father, who has been beating me; it is always her doing when there is any quarreling among the immortals."

Hera, the sister-wife of Zeus, with whom the king of the gods agreed to share power, certainly deserves her own temple and city, in a place of divine beauty. Pamukkale was that place.

Pamukkale (Turkish for cotton castle) in Denizli in southwestern Turkey, is where nature has worked a miracle over the past millennia: The area is endowed with many hot springs. When the calcium-rich water reaches the surface from the depths of the earth, carbon dioxide de-gasses from it, and calcium carbonate is deposited as a soft gel, before it eventually crystallizes into travertine.

The terraced landscape is bleached and smoothed. The result is a snow-white color and a shimmering sheen that could be said of Hera's supple, spotless skin.

On top of this, in total about 2700 meters long, 600 meters wide and 160 meters high, Hierapolis, or the city of Hera, used to sit. Today, the ancient Greco-Roman city could only be called ruins, with its history parceled up in museums. (Visitors can still bathe - and pose for pictures - in the nearby Roman bath, while taking extra caution to avoid getting hurt by the architectural debris - a fallen Roman column for example - that lie scattered on the bottom of the pool.)

However, the natural beauty alone could do justice to the goddess who rules over Mount Olympus. Water drips over a vast mountainside, collecting in terraces and forming milky pools reflective of the pale blue sky. On the day of my visit, a young couple wearing white facial masks immersed themselves neck-deep in one of the pools. The resultant color correspondence created a stunning piece of performance art. (The pristine landscape also provided a perfect backdrop for two Muslim girls donned in white.)

The hand of water, which over the past hundreds of thousands of years has stroked the white ground surface numerous times, had created fine folds, so fine and visually rhythmic that they reminded me of the pleated grains on a clam shell.

Legend has it that the formations are solidified cotton - the area's principal crop - that giants left out to dry. But to me they appeared more like petrified snow, untrodden, untainted, softened by nothing but the rose-colored sunlight.

In Greek mythology Hera is partly defined by her tireless pursuit and persecution of those who were seduced into amorous relationships by her forever adulterous husband, as well as those mortals who, often unintentionally, offended her. If the envious goddess came to inspect the Turkish land today, it is highly likely that she would want to pour her envy onto Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The reason is simple: the latter commands Turkey's best-preserved Greco-Roman city, albeit a small one, dedicated to any Olympian god or goddess.

Aphrodisias is in the historic Caria cultural region of western Anatolia, just about one and half hours' drive from Pamukkale. It is here that the goddess, who has long been featured in Western art as a symbol of female beauty, had her cult image, the Aphrodite of Aphrodisias.

Born from foam off the coast of the Greek Island of Cythera, Aphrodite is associated with love, pleasure and procreation. True to that calling card, she was frequently unfaithful to her husband, the god of blacksmiths, and seduced both men (two shepherds) and deities, before giving birth to many illegitimate children.

On site at the Aphrodisias, a giant marble male nude stood surrounded by dilapidated walls, whose muscular bulk were set against the cloudless blue sky. This is the ideal male figure that could have aroused the goddess, and one that the young Greek men must have had in mind when they worked out in the city's unique 170 m pool two millennia ago, beads of water glistening on their healthy, sun-tanned skin. (On other occasions, during certain celebrations, young men brushed their skin with olive oil and ran naked in the stadium, in the name of their goddess.)

Yet despite its seemingly hedonistic side, the cult of Aphrodite in fact had to it a pointedly political dimension: Gens Julia - the family of Julius Caesar, Octavian August and their immediate successors - claimed divine descent from the goddess. With a row of giant pillars pointing to the sky, the Temple of Aphrodite evokes the days when people ate, loved and prayed in her name.

From Artemis the maiden goddess to Hera the faithful wife and guardian of marriage to Aphrodite the eternal lover, the three deities, all enshrined on the Turkish land at one time, made up a prism to womanhood.

The Aphrodite of Aphrodisias, on view at the on-site museum, is carved out of quality white marble, for which the area was famous. (It must be noted that although in Greek mythology Aphrodite is depicted as having the best proportioned female body, the marble statue is in fact more matronly than sensuous.)

The plentiful storage of the stone also resulted in an abundance of marble sculptures, of both gods and emperors, which have been unearthed during archaeological excavation of the city and now populate the museum.

From the sleek, elastic skin and exuberant curls to the sinewy muscles and silken, curve-revealing fabrics and drapes, the naturalistic rendition points not only to the consummate craftsmanship of the carvers and their observant eye, but also to an aesthetic that is essentially humanistic, an aesthetic that, one and a half millennia on, exerted profound influence on the Western world.

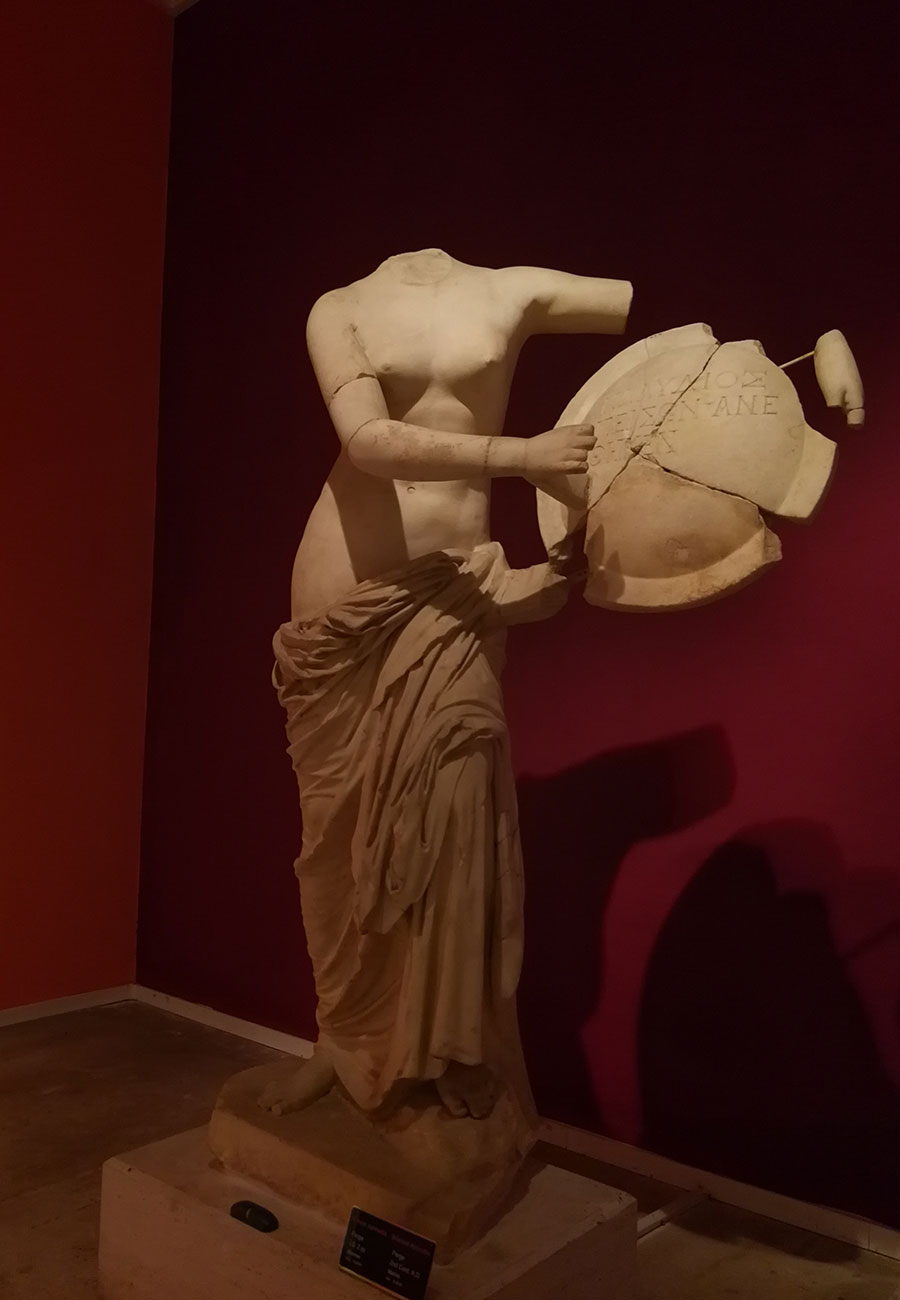

One sculpture particularly caught my attention. Severely impaired, it depicts a tragic moment in the Trojan War. After a whole day of battle, Penthesilea, the Amazonian queen and a female warrior who sided with Troy, confronted Achilles, the Greek hero known for slaying Hector, a Trojan prince and its greatest fighter, just outside the gate of Troy. Achilles killed Penthesilea, only to fall in love with her the moment he took off her helmet.

That takes us back to the Trojan War, a war caused by the feud between three goddesses - Athena, Aphrodite and Hera, all possessed of immense hubris.

According to Greek mythology, the three beautiful goddesses vied for a prize apple upon which was the inscription "To the fairest". And it was up to Paris, a Trojan prince, to deliver the final judgment. Determined to win, each goddess secretly bribed the young man with something. While Hera promised power, Athena offered wisdom and military triumph.

However, it was the gift from Aphrodite - Helen of Sparta, wife of the Greek king Menelaus and the world's most beautiful woman - that Paris found irresistible. By accepting that gift and awarding the apple to Aphrodite, Paris received Helen as well as the enmity of the Greeks and Hera.

The Greeks sent an expedition to retrieve Helen. The war lasted 10 years, with various goddesses taking their sides. The result was countless deaths, and the defeat of Troy by the Greeks.

The vanity of goddesses, the heroism of men, friendship and infidelity, love and loss, bravery and brutality, tricks, travails and tragedies - the Trojan War may have been influenced by divine power, but it was reflective of all things that are utterly human.

"Stripped of its plot, the Iliad is a scattering of names and biographies of ordinary soldiers: men who trip over their shields, lose their courage or miss their wives. In addition to these, there is a cast of anonymous people: farmers, walkers, mothers, neighbors who inhabit its similes," wrote the renowned British poet Alice Oswald.

Homer would probably have agreed. "Like the generations of leaves, the lives of mortal men," the man sighed in the Iliad, in which heroes fell and then were resuscitated by divine intervention, only to fell again and forever.

"Now the wind scatters the old leaves across the earth, now the living timber bursts with the new buds and spring comes round again. And so with men: as one generation comes to life, another dies away."

The fury of the gods and goddesses has long subsided, and the seething sea through which the Grecian fleets sailed toward Troy has calmed.

The moment of the most heartrending beauty for Pamukkale came at sunset, when light drenched the white mountain in colors from burnt orange to crimson to ocher. The changing hues added an element of drama to the place's solemn and stately beauty.

And drama is what the goddesses loved, judging by the fact that no Greco-Roman city is complete without a theater. Magnificently built with wonderful sound-gathering effect, theaters formed a crucial part of the locals' public life, with a far-reaching effect that many believe has influenced Western democracy.

We left Pamukkale at dusk, the place wrapped in a velvety blue, and Homer's words from the Iliad came to mind. "Any moment might be our last," he wrote, the original in Attic Greek. "You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: