DepthReading

Research finally answers what Bronze Age daggers were used for

Introduction

Daggers are ubiquitous yet poorly understood artifacts from prehistoric Europe. They first appeared near-simultaneously in eastern/central Europe, the Alps, and the Italian peninsula in the early 4th millennium BCE1,2,3,4. From the outset, daggers were made from either flint or copper (first alloyed with arsenic, and later with tin) depending on source proximity and cultural preferences. By the early 2nd millennium BCE, daggers were being made, used, and exchanged from Crete in the south to Scandinavia in the north, and from the Russian steppes in the east to Ireland in the west. After this cross-material floruit, flint and metal daggers parted ways, with the former all but disappearing from the archaeological record and the latter continuing to be made and used throughout the Bronze Age5, 6.

Early metal daggers were long thought to be non-functional insignia of male identity and power due to perceived weaknesses in design and alloy composition7, 8. Pioneering applications of metalwork wear analysis suggest that this might not be the case. Wall’s9 examination of 55 Early Bronze Age daggers from southern Britain, for example, indicates that protracted use, repairs, and curation were not uncommon. Similarly, Dolfini10 and Iaia and Dolfini11 noticed high rates of edge sharpening coupled with minor edge damage on 15 Chalcolithic daggers from Italy. They proposed that the damage might be due to contact with soft materials such as animal tissue. Generally, size reduction due to repeated sharpening is common on prehistoric metal daggers, denoting a preoccupation for keeping these objects sharp throughout their use lives12, 13.

None of these studies is conclusive due to their narrow regional and chronological samples. Even if deployed on larger assemblages, however, usewear analysis is unlikely to address broad questions concerning the function of early metal daggers due to (a) high rates of edge corrosion; (b) certain uses not leaving discernible traces; and (c) some of the traces being unspecific. Under these circumstances, insights into dagger uses can be provided by the organic residues trapped in the objects’ corroded surfaces, or by their imprints, which may reveal the substances they had been in contact with. Such an approach has long been applied to ancient stone, shell, and ceramic artifacts but never (to the best of our knowledge) to copper-alloy tools or weapons14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

In this paper, we discuss non-destructive organic residue analysis as performed on ten freshly excavated copper-alloy daggers from Pragatto, a Bronze Age domestic site in northern Italy. We present (a) the site and context; (b) results of qualitative residue analysis carried out on the daggers; (c) results of SEM–EDX analysis; and (d) details of the analytical method. We demonstrate that the research sheds new light on the uses of Bronze Age daggers. Importantly, the approach presented here can be replicated on other copper-alloy tools and weapons from world prehistory. It is therefore a significant addition to the analytical toolkit available to students of the human past.

Archaeological context

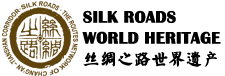

Pragatto (Bologna, Italy) is a prehistoric settlement site excavated in 2016–201723. The site is part of the broader Terramare settlement system, which characterized human occupation of the Po River valley, northern Italy, in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, c.1650–1200 BCE24. The Terramare system emerged in the early stages of the Middle Bronze Age due to combined demographic growth, likely population transfer from Alpine lake-side villages, and a novel ability to manage wet and riverine landscapes, which enabled large-scale crop cultivation of heavy alluvial soils25, 26.

Terramare sites are square villages ranging from 1 to 20 hectares in size. They were normally built near rivers or streams, whose courses were diverted to fill in the ditches surrounding the sites; embankments and palisades also encircled most sites27, 28. The Terramare settlement system provided a stable framework for sociopolitical organization in north-eastern Italy until the advanced Bronze Age. The system dramatically collapsed c.1200 BCE due to either climatic deterioration or political instability, and perhaps both28, 29.

At Pragatto, controlled excavations covered a 6900 sqm area (Fig. 1A) corresponding to the southern portion of the Bronze Age village (Fig. 1B, areas A and B) and surrounding ditch and banks (Fig. 1B, area C). Site stratigraphy and cultural materials were found to be best preserved in area B thanks to a large fire that swept through the village in prehistoric times. Here, investigations revealed nine burnt-down houses, refuse pits, animal pens, and other features. Due to its excellent preservation, area B returned large numbers of portable finds including over 150 bronzes, e.g., daggers, arrowheads, and craft tools of various descriptions23, 30.

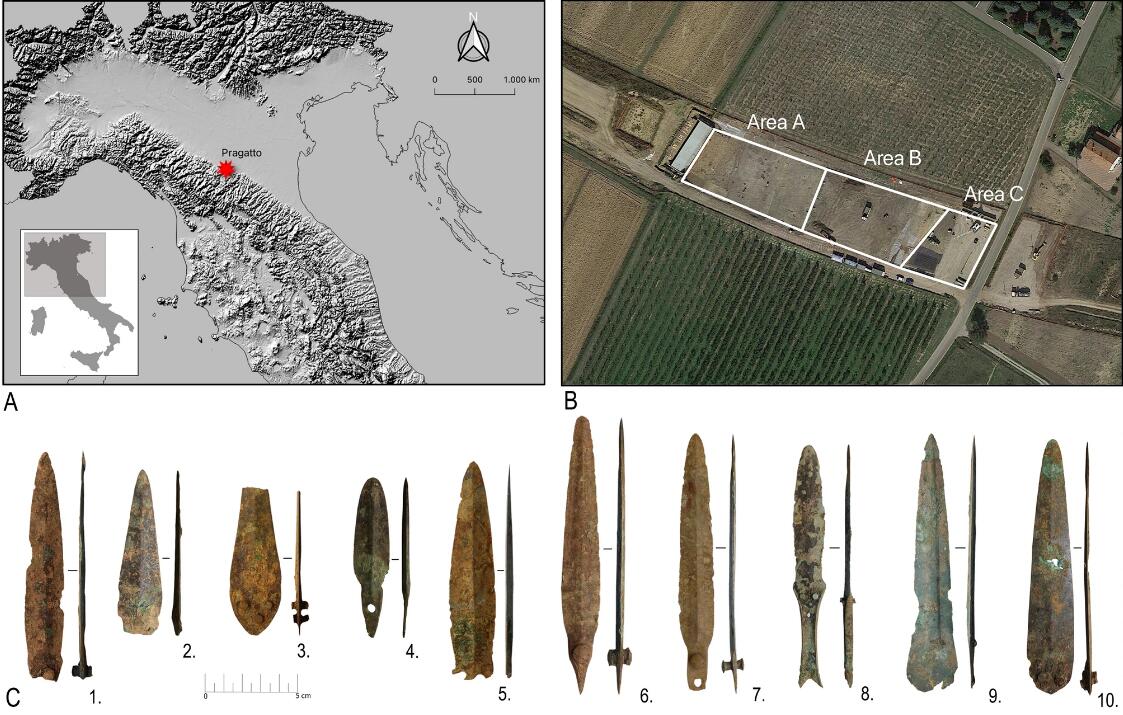

(A) Site location (the map was generated by I.C. through QGIS v.3.16, https://qgis.org); (B) Aerial view of the site highlighting excavation areas A, B and C (source: Google Earth); (C) Copper-alloy daggers analyzed as part of the research. Specimen (1) no 1617; (2) no 2037; (3) no 175; (4) no 1707; (5) no 2041; (6) no 1798; (7) no 2035; (8) no 1683; (9) no 1321; (10) no 264.

Ten daggers were selected for the research, eight from area B and two from area A (Fig. 1C). The sample offers a broad range of blade morphologies, lengths, and hafting arrangements widespread in the Bronze Age including leaf-shaped and triangular blades. Except for one specimen, whose bronze handle was cast with the blade (Fig. 1C, 8), all dagger blades were riveted to handles made of now-disappeared organic materials. Chronologically, the daggers span the period from c.1550–1250 BCE, as revealed by their find contexts and distinctive typologies (SI Appendix, S1).

Results

Microscopic observation and SEM–EDX analysis revealed traces of organic residues preserved on the cutting edges, blades, and hafting plates or tangs of the daggers. Using Picro-Sirius Red (PSR) solution as a staining material allowed us to identify micro-residues of collagen and associated bone, muscle, and bundle fibers of tendon, suggesting that the daggers had come into contact with multiple animal tissues. SEM observation showed the residues to be clustered along the cutting edges and at the junction between dagger blade and hafting plate/tang. The residues were mostly trapped within metal corrosion products and striations sited on cutting edges, which we interpret as use marks10, 11. A similar association of organic residues and striations was observed on replica daggers used for experimental butchering and the working of hard and soft animal tissues (SI Appendix, S2). The interpretation presented here is supported by SEM–EDX analysis of the residues extracted from the archaeological daggers. The analysis revealed abundant hydroxyapatite (HA), a calcium phosphate present in the mineral fraction of the bone31.

Previous research clarifies the conditions—such as contact between organic matter and the copper metal—that prevent bacterial decomposition while preserving animal tissue intact. Langejans32 demonstrates that combined salt and metals can inhibit the activity of microbes and enzymes, enabling protein-muscle tissue to survive. Likewise, Grömer33 argues that the acids and tannin contained in soil sediments (e.g., peat bogs) enable preservation of protein-rich organic matter (e.g., wool, skin, hair, and horn), while Janaway34, 35 makes a similar argument for textiles preserved within metal corrosion products.

Organic residues

Organic residues were searched for on all ten daggers. Areas observed included blade face, cutting edge, point, and hafting plate or tang (both sides). We identified organic residues on eight specimens (SI Appendix Tables S2,

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: