DepthReading

The Salvation of Mosul

Salih reports that ISIS “looted all movable objects” from this tunnel at ancient Nineveh. (Alice Martins)

Salih, the head of the Heritage Department at Nineveh Antiquities for Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, had first arrived at this site two weeks earlier, investigating a military report that the extremists had burrowed a tunnel under Jonah’s Tomb in search of buried antiquities. (Looted treasures constitute a lucrative source of revenue for ISIS.) On that visit, she had entered the tunnel—and soon found herself deep inside a lost 2,700-year-old Assyrian palace carved in the bedrock. Walls inscribed with cuneiform, a winged bull and a worn-away frieze of three robed women—all left intact because the militants apparently feared collapsing the tunnel if they tried to remove them—materialized out of the gloom. News of her discovery had rocketed around the world. Salih had been “incredibly brave...working in extreme danger, with the tunnel in danger of collapse at any time,” said Sebastien Rey, the lead archaeologist of the Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Program at the British Museum. He called the initial reports about her find “extremely exciting...[indicating] something of great significance.”

Now Salih had returned to show me what she had uncovered. We squeezed through winding passages illuminated only by Salih’s iPhone flashlight, sometimes crouching painfully on the hard-packed earthen floor to avoid smacking our heads on the low ceiling. Salih cast her light on an ancient well, and on a pile of blue uniforms in a corner. “They belonged to the prisoners who dug the tunnel,” she told me. I breathed in the musty air, fearful that the passageway might cave in at any moment.

Then, barely visible in shadows from the pale stream of her flashlight, a gypsum wall inscribed with thousands of tiny, wedge-shaped characters appeared. Without an expert to guide me through the murk, I would easily have missed them; Salih had stumbled upon them while carefully probing the tunnel for statuary. We were gazing upon hitherto unseen traces of one of the world’s oldest writing systems, an intricate cuneiform alphabet, invented by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia some 5,000 years ago. Cuneiform provided a historical record of the kingdoms that had flourished in the Fertile Crescent, the intersection of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, at the very dawn of civilization. Scribes had scrawled the epic tale of demigods and monarchs, Gilgamesh, in cuneiform using a reed stylus on clay tablets around 2,000 B.C.

Salih had already sent photos of some of the inscriptions to the chairman of the archaeology department at the University of Mosul, Ali al-Jabouri, a longtime colleague—“he is as fluent in cuneiform as I am in Arabic,” she said cheerfully—and received a translation. The writings confirmed that the palace had been built for King Esarhaddon, who ascended the throne of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 680 B.C. after the assassination of his father, Sennacherib, and his defeat of his elder brothers in a civil war. His great accomplishment during his 11-year reign was rebuilding Babylon, the capital of a rival state that had flourished near today’s Baghdad, and restoring the statues of its gods after his father had razed the city.

This startling discovery was the latest in a series of daring rescue missions that Salih has embarked on since Iraqi forces began their offensive against the Islamic State in Mosul in October 2016. As a scholar specializing in the art and archaeology of the Abbasid caliphate, which ruled the Middle East from the eighth century until the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258, Salih had spent much of her career ensconced comfortably in museums and libraries. But the war has thrust her overnight into a surprising new role—combat zone archaeologist, racing to save ancient artifacts and bear witness to the devastation that the jihadists have left behind.

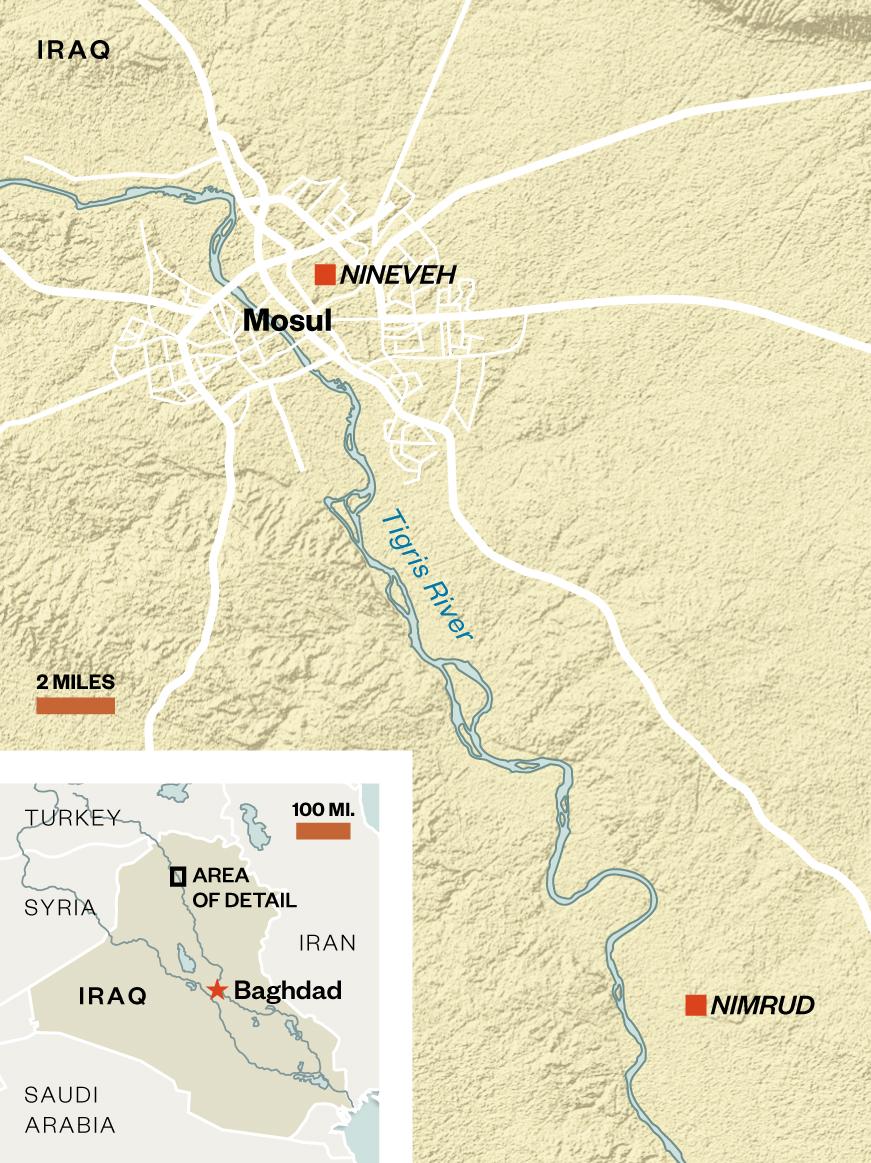

Last November she was one of the first noncombatants after the retreat of ISIS to reach Nimrud, the ninth-century B.C. capital of the Assyrian kingdom, located on a plain overlooking the Tigris 20 miles south of Mosul. Salih documented the destruction, and implemented an emergency plan to protect the bulldozed, smashed remnants of the 3,000-year-old city.

The day before we met, she had traveled with Iraqi Federal Police escorts into western Mosul, where as many as 3,000 Islamic State militants were holed up for the final battle, determined to fight to the death. Dodging sniper fire and mortar blasts in a three-minute sprint down rubbled streets, she clambered through a hole that the terrorists had blasted into the Mosul Museum, a repository for the art of three civilizations spanning three millennia. Salih, a curator at the museum for a decade before the invasion, methodically documented the damage they had inflicted before fleeing.

Two limestone lamassus, huge winged bulls with human heads that had once guarded the palace of Nimrud, lay smashed into fragments, along with a limestone lion and tablets engraved with cuneiform verses and bronze remnants of the Balawat Gates from an Assyrian temple. The terrorists had cleaned out the Hatra Gallery, once filled with Greco-Roman-influenced marble statuary from Hatra, a pre-Islamic trading city on the major trading routes between the Roman Empire in the west and the Parthians in the east. They had also stolen 200 smaller objects—priceless remnants of the Assyrian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Persian and Roman empires—from a storage room. “I had had an idea about the destruction, but I didn’t think that it was this kind of scale,” said Salih, who had inventoried many of the artifacts herself over the years and knew precisely what had been stolen. After making her way to safety, Salih filed a report to the International Council of Museums (ICOM), a group that provides help to the United Nations and other international organizations in areas afflicted by war or natural disaster. The faster the word got out, she explained, the better the chances that the artifacts could be recovered. “Interpol can follow the [looted] objects across the Iraqi border,” she said.

This past January, Iraqi troops discovered a trove of 3,000-year-old Assyrian pottery stashed in a house in Mosul occupied by the Islamic State. Salih rushed into this combat zone after midnight to retrieve 17 boxes of stolen artifacts, including some of the world’s earliest examples of glazed earthenware, and arranged their shipment to Baghdad for safekeeping. “She is a very active person,” Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, Iraq’s most famous archaeologist, who worked closely with Salih while serving as head of museums in Nineveh province before the Islamic State invasion, told me. “She has always been like that.” Maj. Mortada Khazal, who led the unit that recovered the pottery, said that “Layla is fearless.”

In Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, on a sunny spring morning, I picked up Salih at the modest home that she rents with her twin sister and their disabled mother. “We have to live with our mother, because she is handicapped,” she told me, as we drove out of the sprawling oil-boom town of 1.7 million people. “That is one reason that I could never get married.” Sometimes, she admitted, “I feel it is a big sacrifice.” We entered the treeless plains of Kurdistan, passing tent camps for the displaced and checkpoints manned by the Kurdish forces known as the Peshmerga. Then we veered off the highway onto a dirt road, and went through more checkpoints, these run by a patchwork of ethnic and religious militias that had helped liberate areas east of Mosul. We approached a guard post manned by the Shia militia group known as al-Hashd al-Shaabi, identifiable by the colorful mural on their hut showing Imam Ali, the prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law. Salih, a Sunni Arab, tucked her hijab under her chin, Shia style, as a precaution. “To be honest, the Shia militia sometimes [treats] the people worse than the other groups do,” she said. The fighters smiled and waved us onward.

The dirt road wound up to a grassy plateau high above the Tigris River. Here lay the ruins of Nimrud, which had reached its apex under King Ashurnasirpal II around 860 B.C. Sometimes compared to the Valley of the Kings in Egypt for archaeological riches, the walled capital was an urban center with a complex irrigation system, a massive royal palace and a sprawling temple complex. Both were decorated with winged-bull guardians at the gates and magnificent friezes—bearded archers, charioteers, angels—on the alabaster and limestone walls. Cuneiform inscriptions described a luxurious enclave filled with Edenic splendors. “The canal cascades from above into the [palace] gardens,” declared the Banquet Stele, a sandstone block containing a 154-line inscription and a portrait of the king. “Fragrance pervades the walkways. Streams of water [numerous] as the stars of heaven flow into the pleasure garden.”

The British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard conducted the first large-scale excavations of the site in the mid-19th century. A hundred years later, Max Mallowan and a team from the British School of Archaeology in Iraq conducted additional excavations, often joined by Mallowan’s wife, the crime novelist Agatha Christie. Then, in 1988, Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein and his team began digging in the same area that Mallowan had excavated—the domestic wing of the Northwest Palace—and revealed the full glory of Nimrud to the world. Here lay the stone sarcophagi of Assyrian queens, including the wife of Ashurnasirpal II. Hussein, the first to locate and excavate the Queens’ Tombs, found they contained a remarkable array of gold, jewels and other objects weighing more than 100 pounds. “It was my greatest discovery,” he told me with pride.

Saddam Hussein summoned Muzahim to his palace in Baghdad to thank him. Today the riches are stored in the Baghdad Central Bank, and have been publicly displayed only twice—in the late 1980s and again briefly during the chaos that followed the 2003 U.S. invasion, to reassure the public that they had not been stolen.

A young police officer from modern Nimrud, a riverside village just down the hill, approached Salih and me as we waited outside a white military tent for an escort to the ruins. He said he had been guarding the ancient capital in October 2014, four months after the occupation began, when 20 Islamic State fighters arrived in four vehicles. “They said, ‘What are you doing here?’ We said, ‘We are protecting the site.’ They screamed, ‘You are the police! You are infidels.’ They beat us, whipped us, and took our money.” Later, in October 2016, he adds, “They came with bulldozers, and they knocked down the ziggurat.” He gestured to a truncated lump a few hundred yards away, the remains of a towering mud-brick mound dedicated by Ashurnasirpal II to Ninurta, a god of war and the city’s patron deity. “It was 140 feet high, and now it is one-quarter of that size,” the officer said. “It is very painful for us to talk about [the destruction]. This provided people with a living, and it was a source of pride.”

In March and April 2015, the Islamic State bulldozed the ancient wall surrounding the city, dynamited the palace, and hammered to obliteration nearly all the friezes that had covered the palace’s brick walls. They also smashed to pieces the site’s lamassus—the statues that guarded the entrances to palaces and temples. (Most had been carted off by archaeologists to the Louvre and other major museums.) “We had a colleague in Nimrud updating us with information about the site,” Salih told me. “Day after day he would give us news. It was so dangerous. He could have been killed.” On the 13th of November, Iraqi forces recaptured Nimrud. “I got a chance to visit this site six days later,” Salih told me. “It was massive destruction.”

Trudging along the windswept mesa with four soldiers, Salih pointed out an expanse of broken brick walls, and heaps of stone fragments partially concealed by plastic sheeting. Salih had laid the sheathing during previous visits, a rudimentary method, she said, for protecting rubble from the elements. I caught a glimpse of a stone arm, a bearded head and a sliver of cuneiform on a broken frieze, all that was left of some of the grandest pre-Islamic art in the world. The winds had ripped away covers and exposed pieces of bas-reliefs; she covered them, and weighted down the tarps with stones. Salih pointed out one relief clinging to a wall: a winged deity carrying a pine cone and a bucket, objects apparently used in an Assyrian sacred ritual. “This is the last frieze that wasn’t chiseled away,” she said.

Salih insisted that all was not lost. “Finding all this rubble was actually a positive sign for us, for reconstruction,” she said. In fact, the Smithsonian Institution had signed an agreement with the Iraqi Ministry of Culture’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage to assist in the future reconstruction of Nimrud. “The first priority is to build a fence around it,” Salih told me as we walked back to our vehicle. “We must keep the rubble in storage, start the restoration, and rebuild the wall. It will take a long time, but in the end, I am sure we can do something.”

Long before she began documenting the Islamic State’s depredations, Salih was well versed in her country’s cultural heritage. The daughter of a soldier turned shopkeeper in Mosul, she first saw Nimrud as a 14-year-old, picnicking with her class beside the ancient city. Though she was struck by the “huge winged figures” guarding the palace gates, she mainly recalls being bored. “I remember running around with the other kids more than seeing the site,” she says with an embarrassed laugh. Even in subsequent visits with her parents as a teenager—a springtime ritual for Mosul families—she remained ignorant about Assyrian civilization. “There were no TV programs, no information about our heritage, so we had no idea what we were seeing.”

Eventually she found a book about Nimrud in the school library, and read whatever she could find about excavations in the Middle East. She caught the bug. As she approached high school graduation, she resolved, “One day I will become a professional archaeologist.” Salih’s determination was met mostly with ridicule from neighbors and acquaintances. “Mosul is not open to the idea of women having professional lives, except for being a teacher or doctor,” her brother-in-law, Ibrahim Salih, a surgeon, told me. “Archaeology especially involves a lot of outdoor work with men, so it is frowned on.” The typical thinking of many of her neighbors, Layla Salih said, was “Why are you studying all night? Why don’t you get married and have children?”

Photographs by Alice MartinsRead more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/salvation-mosul-180964772/#oPWBp8Byq0TClfEq.99

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: