DepthReading

An Overview of the Silk Road: Time, Space and Themes (Part1 Time)

An Overview of the Silk Road: Time, Space and Themes

The Silk Road in the Digital Space

The Silk Road in Rare Books is a series of ten articles that have been compiled based on the rare books contained in the Digital Silk Road archives (See the list of articles in the table of contents on the right). In this introductory article, we take a look at the overall history of the Silk Road in terms of time, space andthemes.

Beginning from the viewpoint of “Time,” we start by tracing the several thousand-year history of the Silk Road from ancient to modern times. We next examine the Silk Road in terms of “Space,” following the main routes which formed these long-distance overland trade roads from east to west. Finally, we take up several notable Silk Road events to explore the history of the Silk Road in terms of themes.

The Digital Silk Road is an attempt to take a fresh look at the scholarly achievements of those archaeologists, art historians and adventurers of the past. In doing so, we seek to look again at the important documents that these scholars left behind, and by digitally archiving them, make these valuable resources more accessible. It is our belief that the documents will serve as a significant resource through which people will be able to utilize from their own individual points of view, and in this way come to create new understandings and interpretations of Silk Road history and culture.

The documents contained in the digital Silk Road archives were compiled in great part by explorers from the nineteenth to the twentieth century (09) who risked their lives to travel over the then-obscure regions along Silk Road in order to make their valuable discoveries. It is our hope that in the future, explorers can travel in this digital world, and in doing so, they too can excavate all kinds of important information buried in the archives. Containing endless possibilities for producing new images of the Silk Road, it is possible that future digital explorers will then go on to share their findings will many others via the Internet; in this way preserving and passing down these valuable resources to posterity.

The Silk Road “Time”

1. Prehistoric Central Asia

Many things remain clouded in mystery regarding the ancient history of Central Asia. However, it is thought that agriculture started in the Tarīm Basin around 4000 BC. Studies undertaken on the Tocharian language (an extinct Indo-European language) suggest that Indo-European peoples first arrived from West Asia moving into the Tarīm Basin around 2000 to 1000 BC (06). Mummies found in Loulan (in the Xiao He Grave site (小河墓) (06), which are estimated to be 3,800 years old, show distinctly Caucasian features, and we therefore know that at one time Central Asia was home to Indo-European people.

2. The Dawn of the Silk Road

Our earliest records of Central Asian history come from Chinese records documenting various Chinese inroads into the e region, as well as recording tribute received from Central Asian nations. . The earliest records appear in the of the Early Han period, under the reign of the Emperor Wudi (141 BC-87 BC). It was under Emperor Wudi that the imperial envoy Zhang Qian (02) made his legendary journey through Central Asia and his reports are contained in such Chinese documents as “Accounts of Ferghana” (in Records of the Grand Historian); Dynastyand “Geographical Accounts of the Western Area” (in History of the Han Dynasty). Although the purpose of his journey was solely political, the information about Central Asia which he brought back was significant in helping to open up trade routes between east and west.

Emperor Wudi, using the knowledge brought back by Zhang Qian, pressed ahead with aggressive military campaigns in Central Asia, sending great generals such as Wei Qing and Huo Qubing to fight against the nomadic Xiongnu (Huns). In 121 BC, he succeeded in expelling the Xiongnu from the Tarīm Basin, and then in 102 BC, he invaded Ferghana in order to extend his control over neighboring countries in the region. The Tarim Basin, home to the important east-west trade routes, as well as being the sole place where superior horses could be obtained, held unending appeal for the Early Han Dynasty emperors. This was especially so concerning Han control of Ferghana, the home of the legendary “Blood Sweating Horses.” (For more on the history of the time and the legendary blood-sweating horses see Digital Silk Road’s “The Horses of the Steppe: The Mongolian Horse and the Blood-Sweating Stallions”) For about 100 years, the Early Han controlled the trade routes passing through Central Asia. It was around this time as well that the Kingdom of Loulan became a puppet state of the Chinese Han, thereby changing their name to Shan-shan in 77 BC (06).

The Han control over Central Asia, however, was loosened for approximately 60 years when Wang Mang usurped the throne and established his Xin Dynasty. Chinese control of the region resumed once again during the Later Han Dynasty, under Emperor Mingdi (57-75 AD). General Ban Chao (a younger brother of Ban Gu, the author of History of the Han Dynasty) ruled the region in a peaceful manner for many long years. During this time, the countries of Central Asia were reduced to subservient status with some under direct Han rule-- and then later Wei and Western Jin rule—and with others retaining their independence but made to pay tribute to the Chinese court. . Of the two different historical periods represented in the ruins found in Mīran (07), the older ruins (date of origin unknown up to end of the third century) were built and abandoned during this period.

|

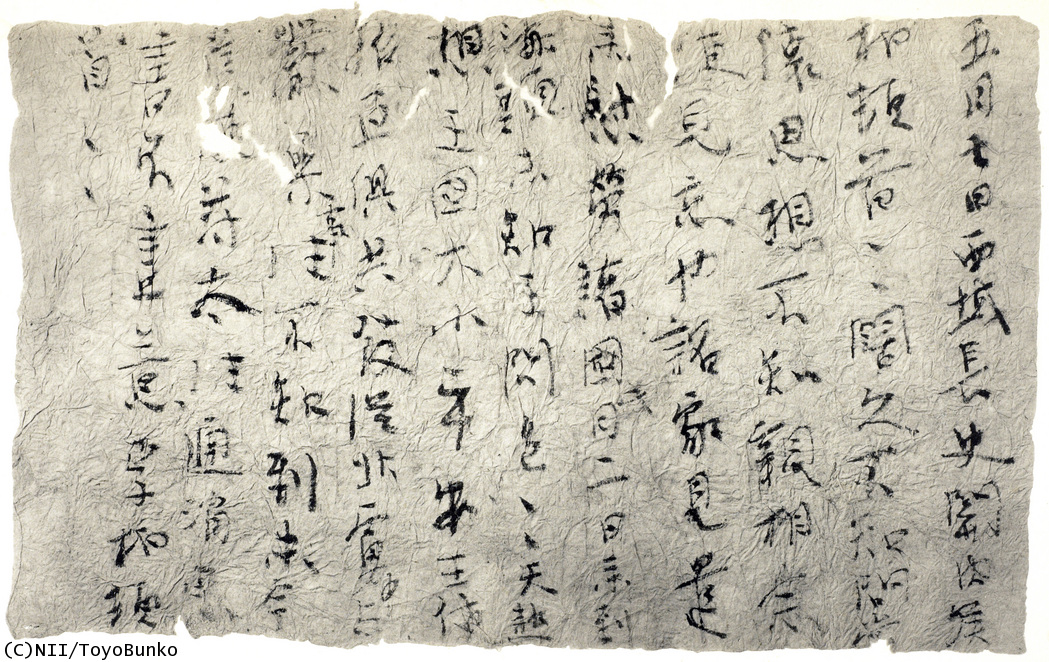

| (1) |

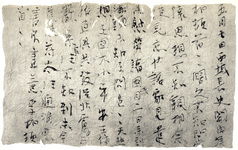

Resulting from the political turmoil which occurred at the end of the Western Jin Dynasty, China was divided into north and south, in what is known as the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420-589). In the north, Chinese and non-Chinese steppe peoples (known collective as the Wu Hu—or five non-Chinese nomadic tribes), established the short-lived Sixteen Kingdoms. Some of these tribes attempted to extend their power over Central Asia, intending to gain control of the trade routes in the region . In the famous “Li Bo Document(1) (in 328) (06) found at Loulan, we learn that the later Liang Dynasty had gained control of the region. During this period, as mainland China fell into political disarray and conflict, the main east-west trade route through the Hexi Corridor became insecure. The Tuyuhun tribe exploited this situation to make forays into the lucrative east-west trade using another route through the Qinghai region during the fourth to the seventh centuries (07).

The period of the Northern and Southern dynasties was also a time when many Buddhist priests immigrated to China from Central Asia. The period saw the flowering of Buddhist culture in Central Asia, and it was in this period that much of the great cave temple art was created in the region. The Kizil Caves (04), for example, were constructed starting in the the late third or the fifth century and the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang (05) in the second half of the fourth century.

3. The Tang Protectorate over Central Asia

|  |

| (2) | (3) |

With the reunification of northern and southern China under the Sui Dynasty, east-west trade in Central Asia achieved unprecedented prosperity. This prosperity was further increased under the Tang Dynasty which came to control a vast area of Central Asia (having overthrown the Qu-shi Gaochang Kingdom (498-640) in Turfan in 640 in addition to its subjugation of other countries in the region). The Tang installed a Protectorate General of Anxi to serve as the base for the management of trade in Central Asia. It also established a Protectorate General of Beiting in 702 to prepare against attacks from Turkish tribes based in the Dzungarian Basin to the north of the Tian Shan mountains.

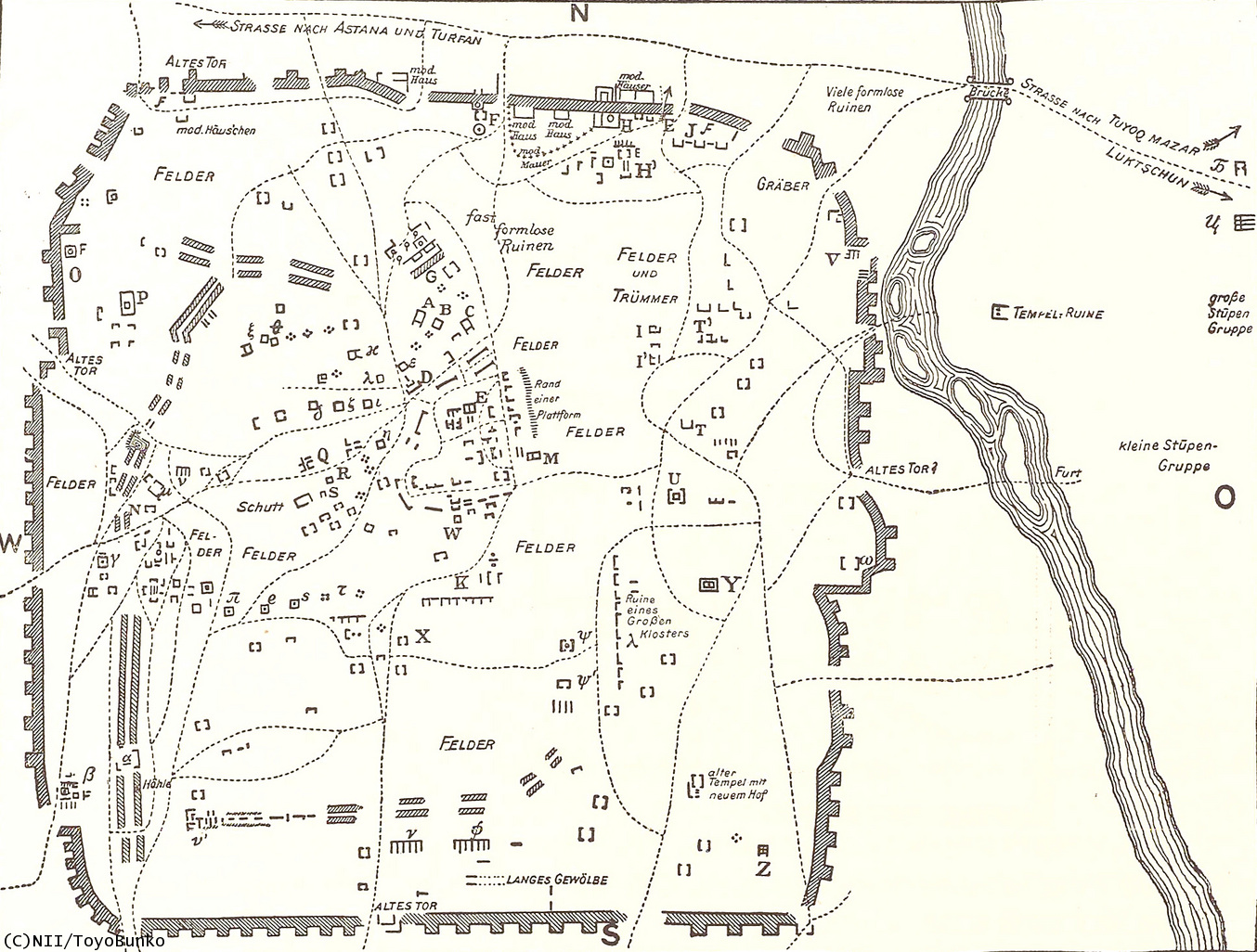

|  |  |

| (4) | (5) | (6) |

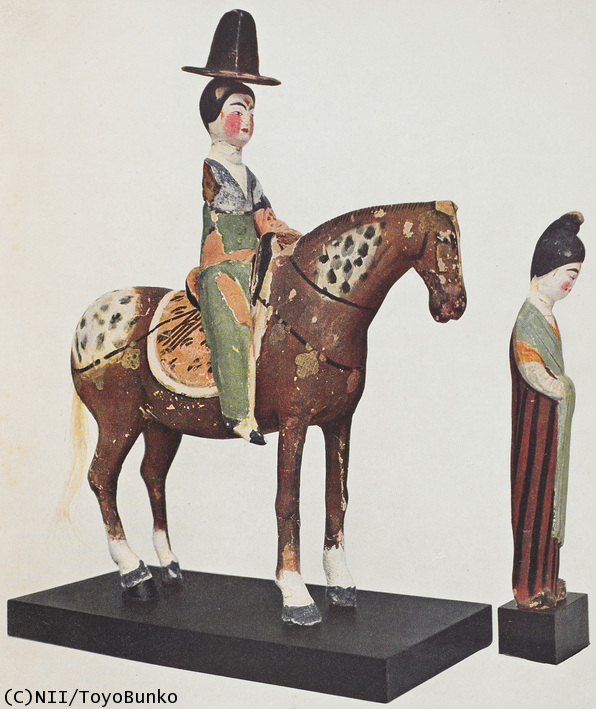

Tang Dynasty influence over Central Asia can be seen in the antiquities found in the ancient cemetery of Astāna, to the north of Kara-Khōja (Sketch Plan of Kara-Khōja by Grünwedel(2), Sketch Plan of Kara-Khōja by Stein(3)), at the Ancient Cemetery of Astāna(4). These antiquities showing a clear Tang influence include Clay Figures(5) and Silk Paintings(6). In addition, Chinese-style Wall Paintings(8) can be found in the Kumtura Thousand Buddha Caves(7) as well.

|  |

| (7) | (8) |

Tang power over the area quickly waned after its defeat against the Arab Abbasid Caliphate at the Battle of Talas in 751. This devastating defeat was then followed by the chaos within China following the the aftermath of the An Shi Rebellion from 755 to 763. With China in chaos, in 786, the Tibetan Tubo Kingdom (07) seized the Hexi Corridor (05). Occupying both the Protectorate Generals of Anxi and Beiting, they therein expelled the Tang from Central Asia. The second period ruins of the Mīran site (07) is that of a Tibetan fort. The ruins of Dandān-Uiliq (near Khōtan (03)) were of a city also deserted at the time of Tang withdraw from Central Asia and the desertion of the city is thought to be linked with the end of Tang power in the region.

4. Turkic-Islamification of Central Asia

|

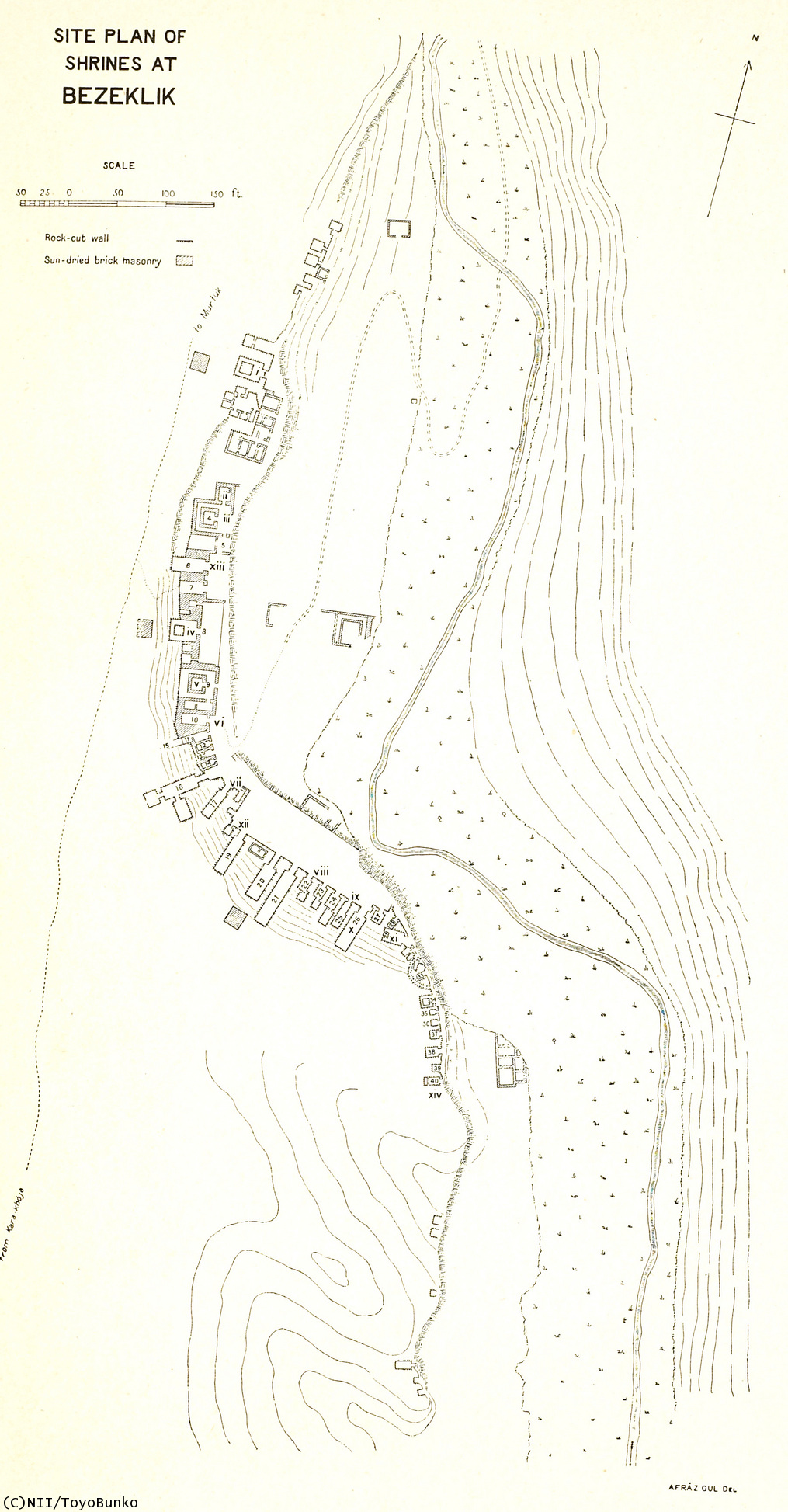

| (9) |

At the end of the eighth century, Uighurs (01, 08), originally inhabitants of the Mongolian Plateau (02) migrated south into the Turfan basin where they establisged their Uighur Empire. The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves(9) (01) were built by Uighurs between the ninth and the tenth century. At Kara-Khōja, for example, banners portraying Uighur donors (01) have been excavated.

During the tenth century, the Turkish Karakhanid Dynasty conquered a large area of Central Asia not including Turfan. These two Turkic Kingdoms, the Uighur Kingdom and the Karakhanid Dynasty, brought the Turkic language into Central Asia—thereby replacing the Aryan people and their languages. At the same time, there was an increased mixing between peoples, which further contributed to the Turkification of the region. In addition, because the Karakhanid Dynasty was Islamic, this contributed to the Islamification of Central Asia (Muhammadan Tombs in Tumshuk(10), Ruin of Muhammadan Tomb in Khara-Khoto(11)). Such was the extent of these influences that the region came to be known as Turkestan, which literally means “the Land of the Turkic peoples” (08).

|  |

| (10) | (11) |

During Song dynasty times in China, the Tangut people established their Western Xia Dynasty (1032-1227) in the northwestern part of China. This powerful state came to control the Hexi Corridor during this period. Fervently Buddhist, the Western Xia constructed new cave temples at the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang , in addition to repairing the older ones which had been built there much earlier. The famous Library Cave (Cangjing-dong, Cave 17) (05), where a great number of manuscripts and paintings were famously found in 1900 was walled up for some reason during the Western Xia period. The Tanguts of the Western Xia also built the city of Khara-Khoto (08) at the point on the Silk Road where two routes (the east-west route connecting outer Mongolia to the Tian Shan and the north-south route connecting the Oasis cities of Jiuquan and Zhangye along Hexi Corridor) come together.

5. The Twilight of the Silk Road

Around the time that Central Asia was becoming both Islamified and dominated by Turkic peoples, the world was seeing great changes in systems governing the movement of goods. In the northern part of Central Asia, for example, a route running east- west through the steppe, which had long been an insignificantly small trade route grew greatly in importance. Maritime trade, something which had long been monopolized by Islamic merchants, gained in significance as well. The discovery of new sea routes by Europeans became the decisive factor in reducing the importance of Central Asia for trade. With these new routes for moving goods, Central Asia slowly lost its significance and later fell into oblivion.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, with its former prosperity long gone, Central Asia once again began to attract attention. This time, though, it attracted attention as a geographical vacuum, luring explorers from all over the world (09).

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: