DepthReading

Sword fighting with Bronze Age weapons is really hard, scientists learn

Hefty Bronze Age swords are an impressive sight, but scholars have long wondered if these swords were primarily ornamental or if they were used regularly in combat. Modern researchers took a closer look at these weapons — even hoisting them in mock battles — and they discovered that not only were these swords battle-ready, using them effectively was a lot harder than it looked.

To see how much damage the swords could inflict, a research group in the United Kingdom called the Bronze Age Combat Project (BACP) brought together experts from universities and museums; and hobbyist volunteers who train in medieval European combat.

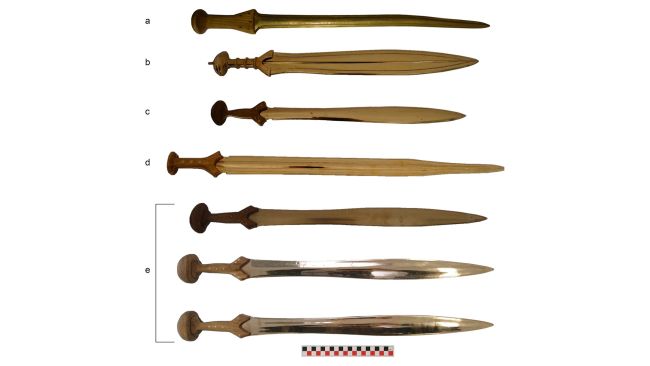

First, the scientists staged controlled experiments with seven replica Bronze Age swords, conducting single-strike tests against other weapons and shields. Next, they used human combatants to test the replicas in combat sequences. The third and fourth phases put the replica swords and 110 real Bronze Age swords from Britain and Italy under a microscope, where researchers scrutinized patterns of scratches, dings, cracks, notches, bends and dents.

People developed the first metal weapons during the Bronze Age, around 3000 B.C. to 1200 B.C. But bronze — tin mixed with copper — is softer than steel and more prone to damage, study co-author Andrea Dolfini, a senior lecturer in later prehistory at Newcastle University in the U.K., said in a statement. Because these weapons could be chipped and notched so easily, ancient blades retain a record of use that the researchers linked to Bronze Age fighting techniques.

Previous research hinted that Bronze Age swords were suited for cutting and stabbing, the scientists reported. Their new analysis of wear patterns on Bronze Age blades showed that sword fighting during that period called for prolonged close-range tussling with a lot of sustained blade contact, using practices such as "sword-twisting and binding," the study authors wrote. They also noted that the swords could be used effectively in thrusting, slashing and cutting stances.

Many of the blades in real Bronze Age swords bore notches that frequently appeared in clusters. These scars hinted that combatants performed the same attack maneuvers many times, "using that same part of the blade," the scientists wrote in their study, which was published online April 17 in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory.

"This suggests that the fighter must have achieved excellent control of the weapon through sustained training," the researchers reported.

Though popular films and TV shows typically highlight the drama of blades striking blades during historic swordplay, real Bronze Age combatants would have avoided direct blade-on-blade blows; such blows could seriously damage or destroy their weapons. Rather, an experienced sword-fighter would seek out a clean body strike because it would be less damaging to their blade, said lead study author Raphael Hermann, an archaeologist with the University of Göttingen in Germany.

"Stab somebody in the guts, and you won’t have a mark on your sword at all," Hermann told Science.

People who fought with swords during the Bronze Age were probably aware that their blades were prone to chipping and scratching, particularly if they clashed with an opponent's sword. Sword fighters would therefore have practiced extensively to learn how to use their weapons "in ways that would limit the amount of damage received," Dolfini said.

"It is likely that these specialized techniques would have to be learned from someone with more experience and would have required a certain amount of training to be mastered," he said.

While these experimental methods may seem unusual, this study isn't the strangest example of using staged reenactments for testing ancient weapons. In 2018, researchers whacked pig carcasses with samurai swords and machetes to evaluate the cutting power of traditional Japanese weapons called katanas, Live Science previously reported.

Like the researchers who swung Bronze Age swords, these scientists also discovered that achieving an accurate katana strike over and over again was much harder than they expected.

"This is not something that one could improvise," the authors of the new study reported.

Category: English

DepthReading

Key words: