锁阳城遗址

锁阳城遗址虚拟重建设计策略Virtual reconstruction design strategy for the Suoyang city site

摘要: 关于丝绸之路遗址的修复与展示研究相对较少;这些遗址是典型的土遗址,由风蚀沙地和零散的墙体部分组成,地面上几乎没有发现遗存。本研究以锁阳城遗址为例,运用无人机倾斜摄影、三维激光扫描、虚拟现实(VR)、增强现实(AR)和人工智能(AI)等数字技术,构建锁阳城遗址的三维数字模型。通过实地调研,本文分析了游客对遗址的感知价值,提取了修复设计元 ...

关于丝绸之路遗址的修复与展示研究相对较少;这些遗址是典型的土遗址,由风蚀沙地和零散的墙体部分组成,地面上几乎没有发现遗存。本研究以锁阳城遗址为例,运用无人机倾斜摄影、三维激光扫描、虚拟现实(VR)、增强现实(AR)和人工智能(AI)等数字技术,构建锁阳城遗址的三维数字模型。通过实地调研,本文分析了游客对遗址的感知价值,提取了修复设计元素的核心要素,并在增强价值感知的基础上提出了遗址修复的数字化方法。研究提出了一种多模态数据驱动的虚拟重建设计流程。研究成果为世界范围内其他城市遗址的虚拟重建提供了技术路径和理论参考。

Abstract

There is relatively little research on the restoration and display of Silk Road sites; these are typical earthen ruins consisting of wind-eroded sandy land and scattered wall sections, and almost no remains are found on the ground. This study takes the Suoyang city site as an example and uses digital technologies such as drone oblique photography, 3D laser scanning, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and artificial intelligence (AI) to construct a 3D digital model of the Suoyang city site. Through onsite research, this paper analyzes the perceived value of the ruins according to visitors, extracts the core elements of restoration design elements, and proposes a digital method for restoring the sites on the basis of value perception enhancement. A multimodal data-driven virtual reconstruction design process is proposed. The research results provide a technical path and theoretical reference for the virtual reconstruction of other city sites around the world.

Introduction

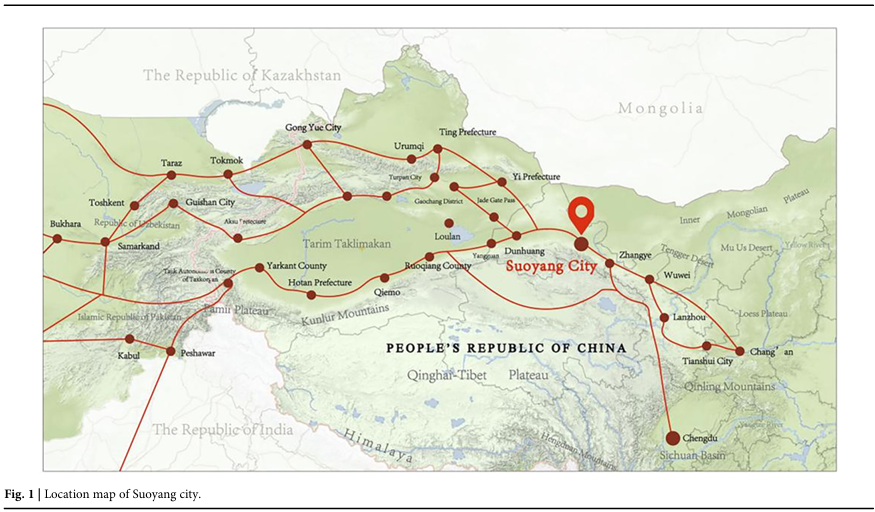

Earthen ruins along the Silk Road represent significant cultural heritage but conserving them is a challenging task. As a key urban node along the Hexi Corridor of the Silk Road, Suoyang city played a central role in supporting military logistics, religious transmission, and cross-cultural exchange during the Tang Dynasty (Fig.1). Its status as a UNESCO tentative list site and the richness of its partially preserved structures make it an ideal case for exploring virtual reconstruction approaches. These sites are especially vulnerable because of the fragile nature of rammed earth structures, which are highly susceptible to erosion and wind and are limited in their ability to mitigate the effects of long-term losses and storms. Their degradation is often irreversible, and traditional physical restoration methods are not useful for different sites1,2,3.

Fig. 1

figure 1

Location map of Suoyang city.

In response to these challenges, virtual reconstruction—including AI-assisted modeling, 3D scanning, and historical data inference—has emerged as a noninvasive and sustainable alternative to digitally reconstruct lost, damaged, or speculative components of cultural heritage sites without the need for physical intervention. Unlike conventional conservation methods, these methods enable precise geometric modeling, virtual reimagination of missing architectural features, and dynamic simulation of original site conditions. These techniques support historical interpretation, public education, and the global dissemination of heritage values while preserving the site’s physical integrity. Moreover, digital reconstruction ensures long-term data preservation and allows for continuous optimization.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and immersive technologies such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) have further expanded the possibilities for digital heritage design. AI-based models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and natural language processing (e.g., BERT) enable automated analysis of multimodal heritage data, ranging from point cloud scans to textual records. When integrated with AR/VR interfaces, these technologies facilitate perceptually enriched reconstruction and immersive visualization, enhancing both technical fidelity and emotional engagement. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) are not cultural heritage technologies per se but rather immersive visualization and interpretation interfaces used to deliver heritage content reconstructed through prior modeling and semantic enrichment.

Gîrbacia, F. analyzed the research trend of applying artificial intelligence to cultural heritage4, and Pan Z.G. summarized the current development status of digital displays and interactive technology for cultural heritage5. The use of 3D scanning technology, digital methods, and information technology for digital modeling and virtual restoration displays can avoid the need for direct contact with cultural ruins, thereby avoiding secondary damage6. Geng G.H. reviewed the development of key technologies for revitalizing cultural heritage collection and understanding, integrating virtual and real elements for intelligent display and interaction, and constructing intelligent platforms7,8. Skublewska Paszkowska.M. reviewed the application of 3D technology for the protection of intangible cultural heritage and emphasized the importance of digitization in preserving and disseminating traditional skills9. Hu, Z. used digital methods to visualize and analyze the cultural landscape genes of traditional Chinese settlements from a semiotic perspective, revealing their unique cultural connotations10. Yu J. analyzed the interactive mechanism of virtual and real complementarity, virtual and real intelligence connections, and virtual and real fusion for the protection and activation of large archeological ruins empowered by the metaverse 11. Chiara I. contributed to the development and incorporation of AR, MR, and VR applications for cultural heritage preservation12. AR technology is gradually being applied at large archeological sites for exploration purposes13,14,15,16. Huang, Y. Y explored the application of knowledge graphs and deep learning algorithms in digital cultural heritage management, aiming to improve the efficiency of organizing and retrieving heritage information17. Guo L. focused on the San Su Shrine—a quintessential example of a Xishu Garden—and explored the application of digital technologies in the commemorative research and quantitative preservation of these gardens18. Research on the application of augmented reality technology using smartphones as terminals in the display of archeological sites is rapidly developing19,20. Recent critical heritage studies have shifted the understanding of heritage from static monuments to dynamic cultural and political processes21,22,23,24,25. Smith L. emphasized that heritage should be viewed as an ongoing cultural and political practice rather than a fixed material entity21. Similarly, Harrison frames heritage as a constellation of performative and affective practices that shape how sites are experienced and interpreted22. Prior studies in the field have focused largely on geometric reconstruction using photogrammetry, laser scanning, or standard 3D modeling. A key limitation in prior work is the disconnect between digital reconstruction and cultural meaning-making. The literature rarely links the emotional or cognitive responses of visitors with restoration logic. Our study explicitly addresses this gap by using perception data (interviews and text mining) to inform the prioritization and design of restored features. In this way, machine learning is used not only for reconstruction but also as a bridge between visitor values and visual restoration decisions. AR/VR restoration design helps enhance tourists’ sense of experience, immersion, connection, and participation, triggering emotional resonance among the public and activating local cultural heritage through firsthand experiences26,27,28,29,30.

Although various attempts have been made at the restoration design of historical remains, discrepancies often exist between the images perceived by visitors and those projected through reconstructions. Moreover, relatively limited research has focused on the identification of heritage values and the analysis of public value perception of such sites. “Value perception” is defined as the subjective evaluation of cultural, esthetic, and emotional meaning perceived by visitors during interactions with a heritage site. The measurement is based on structured interviews and coded content analysis via the KH Coder (Quantitative Content Analysis or Text Mining Software) and SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

Following Pietroni and Ferdani (2021)31,32, we distinguish virtual (digital) restoration—digital-only interventions aimed at enhancing the legibility of heritage objects without material interference, explicitly including virtual anastylosis (the reassembly of extant but dismembered parts)—from virtual reconstruction, a hypothesis-driven recreation of a site or object at a specific historical moment based on available evidence and reasoned inference, consistent with the transparency and recognizability principles of the Seville Principles (2011). In this study, component-level readability operations (e.g., localized completion and anastylosis) are treated as restoration, whereas the scene-level, historically contextualized immersive model of Suoyang is framed as virtual reconstruction, with uncertainty communicated through confidence coding and paradata.

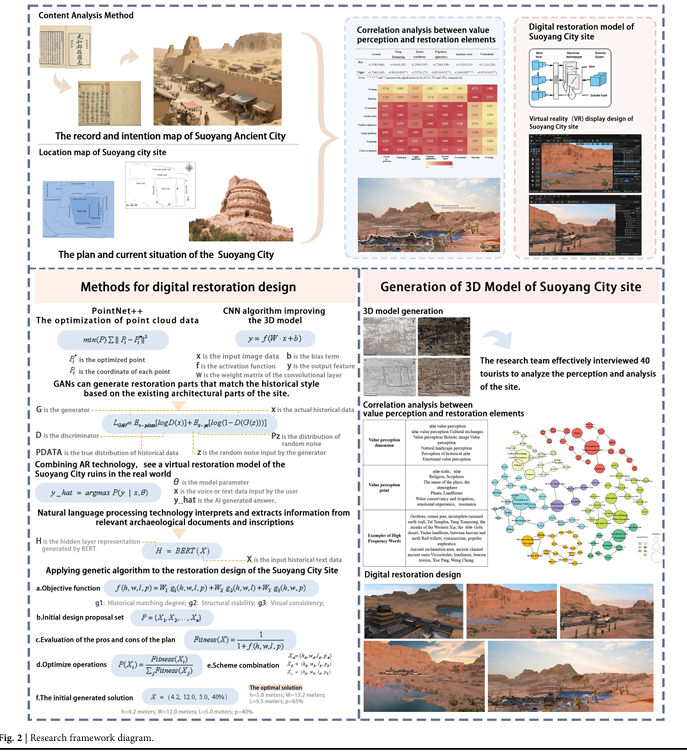

On the other hand, the virtual reconstruction of archeological sites involves a large amount of multimodal data, including point cloud data, photos, videos, and historical documents. In this context, the present study proposes a virtual reconstruction design framework for the Suoyang archeological site that integrates AI-driven modeling, historical document analysis, and visitor value perception into a unified workflow (Fig. 2). The historical documents analyzed in this study encompass four main types: dynastic histories, regional gazetteers, exploration accounts, and modern interpretive materials. To guide this investigation, we address the following two research questions: 1. How can AI technologies support the reconstruction of historically grounded and semantically meaningful heritage features in 3D digital models? 2. How do visitors’ emotional and cognitive perceptions influence the prioritization and spatial emphasis of restoration elements within immersive environments?

Fig. 2

figure 2

Research framework diagram.

This research aims to bridge the technical and experiential dimensions of digital heritage, enabling both accurate visual restoration and culturally meaningful reinterpretation of Silk Road earthen heritage sites.

In recent decades, virtual heritage research has developed a clear theoretical vocabulary distinguishing between several forms of digital intervention. Following the Seville Principles (2009) and subsequent scholarship33,34,35,36. (Bentkowska-Kafel et al., 2012; López-Menchero, 2013; Denard, 2020), three interrelated but distinct concepts are recognized: (1) Virtual (digital) restoration—digital interventions for legibility and hypothesis testing without physical interference; (2) Virtual reconstruction—digital recreation of sites or structures at a specific historical moment based on available evidence and reasonable inference; and (3) Digital/virtual anastylosis—virtual reassembly of extant but dismembered parts. Within this framework, our study integrates all three levels: point cloud reassembly corresponds to digital anastylosis, GAN-based reconstruction represents virtual reconstruction, and the immersive VR/AR visualization constitutes virtual restoration. This mapping clarifies the conceptual scope of the study and aligns it with the established theoretical standards in virtual heritage.

Methods

This section outlines the integrated methodology used to digitally restore the remains of Suoyang city on the basis of multimodal data. The methodology is structured into five interconnected stages: data collection, perception analysis, textual knowledge extraction, AI-assisted modeling, and design integration. These methods collectively support the research objectives of reconstructing, interpreting, and digitally disseminating the site’s heritage values.

Research location

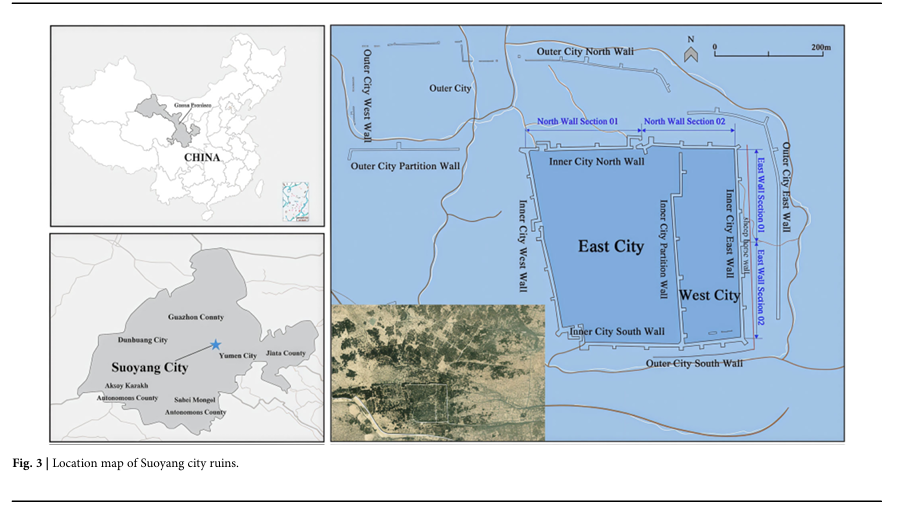

The Suoyang archeological site (Fig. 3) is located in the Gobi Desert southeast of Suoyang town, Guazhou, Gansu Province, China. As a key hub of the ancient Silk Road, Suoyang city not only connected the Western Regions and the Central Plains throughout history but also provided a unique perspective for studying how ancient people adapted to and transformed desert environments. The multilayered historical remains of the site, such as ancient rivers, tombs, and towns, highlight the wisdom and achievements of ancient society in terms of military defense, water conservancy irrigation, and agricultural development in the region37. The Suoyang city site was constructed and utilized by various dynasties, resulting in diverse cultures and architectural styles. As one of the best-preserved ancient cities of the Han and Tang dynasties, the city walls, building materials, and construction methods used in the ruins reflect cultural integration from the Han Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty and other historical periods. Suoyang city is named after the plant “Suoyang”, which was abundant in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. In 2014, the Suoyang city site was included in the World Cultural Heritage List.

Fig. 3

figure 3

Location map of Suoyang city ruins.

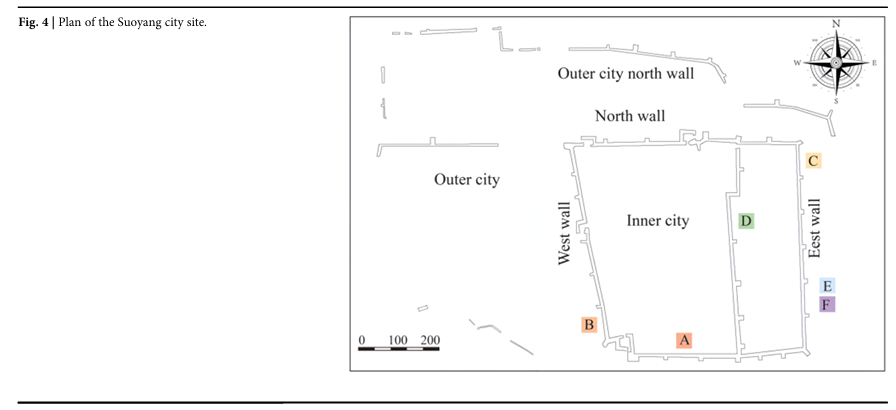

The Suoyang city site covers an area of approximately 8000 square meters and can be divided into an inner city and an outer city (Fig. 4)38. The outer city, also known as “Luocheng”, currently has two low walls surrounding the city. The southern wall has a base width of approximately 4.5 meters, a top width of approximately 3 meters, and a height of 3–4.5 meters; The northern wall base is 8–14 meters wide, the top is 3–4.5 meters wide, and the remaining wall is 4.5–6.5 meters high. The plan of the inner city is basically rectangular, with an east wall length of 494 meters, a south wall length of 458 meters, a west wall length of 516 meters, a north wall length of 536 meters, a partition wall with a length of 500 meters, and a total circumference of 2104 meters. There are a total of 25 horse faces on all four sides, with enemy fortifications built on them (all of which have collapsed). The four corners of the outer city are built using corner piers, and the existing northwest corner pier and the southern corner pier of the partition wall have been well preserved with the use of adobe masonry. An east‒west arch opening is found at the northwest corner pier. There are a total of four city gates on the east, south, west, and north walls of the inner city, and there are moats built outside the gates. There are 26 circular earthen platforms in the western part of the city, which are surrounded by earthen walls that may include the remains of ancient barracks. In addition, there is a small town built in the southeast corner of the eastern part of the city, which may be the location of ancient government offices. There is a northern section of the inner city wall near the north gate.

Fig. 4

figure 4

Plan of the Suoyang city site.

One gate with an existing wall width of approximately 10 meters that once connected the eastern part of the city to the western part, and the city gate remains. The outer and inner cities of the Suoyang city site are connected, which is different from the traditional sense of inner and outer cities. The outer city is shaped like a rectangle, with the northeast corner curved inward, forming a pattern that is wide in the west and narrow in the east. The widest part in the west is approximately 270 m wide, whereas the narrowest part in the east is only 71 m wide. The Suoyang city site has the architectural features of having an inner prefecture city, an outer city known as Luo city, and Yangma city in the urban construction system of the Sui and Tang dynasties38.

Content analysis method

The multidimensional evaluation of tourists’ perceptions of the value of tourist destinations and their identification with the landscape elements of archeological sites can be explored through content analysis. Historical impressions and onsite experiences provide a scientific and reasonable method for analyzing the process of extracting site restoration elements from tourists’ perceived value6,39,40,41,42,43. On the basis of the unique value connotation of the research case of Suoyang city site, this study first starts from the perspective of heritage objects, uses the content analysis method to identify the multiple dimensions of heritage value perceived by tourists, and then reveals the objective impression of the remains. Second, from the perspective of the characteristics of the natural environment of the site, the mechanism through which tourists’ recognition of site elements is formed in the process of value perception is explored, and the virtual reconstruction of various elements of the remains is achieved to express the historical connotation of the archeological site itself. Finally, from the perspective of the immersive interaction between the main body of the ruins and tourists, a digital model of the Suoyang city site is constructed with the restoration design goal of determining the perception of heritage value44,45,46.

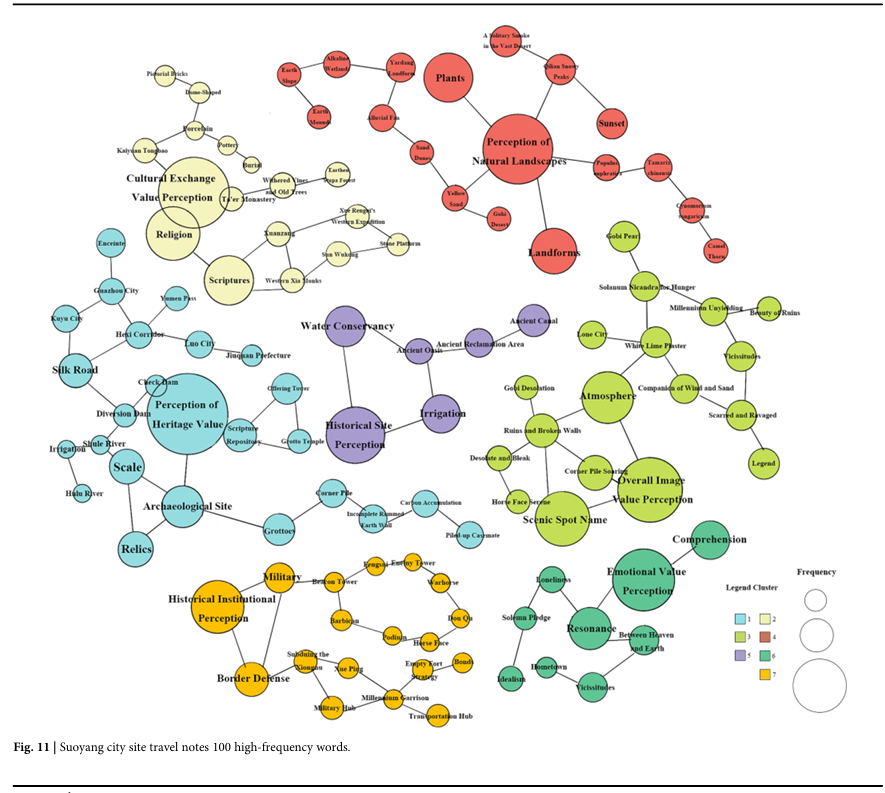

A content analysis method is used to conduct a perceptual analysis of the Suoyang city ruins as the theoretical basis for the restoration design of the Silk Road archeological ruins. Content analysis is a research method that transforms unsystematic, qualitative symbolic content into systematic quantitative data. It can structurally process fragmented information scattered in textual materials and obtain complete information about tourists’ cultural and psychological perceptions of cultural heritage ruins. To ensure the validity of the analysis and scientifically reflect the interactive relationship between the structure of the data, KH Coder was used to translate the interview texts. Following the processing steps of data preprocessing, establishing an analysis dictionary, word frequency analysis, determining effective high-frequency words, and implementing a co-occurrence network, the top 100 high-frequency words are used as the basic analysis units for the value perception content. They are further conceptualized and summarized as value perception nodes, and multiple representations of the value perception of the Silk Road city site are extracted.

The virtual reconstruction of archeological remains includes the construction of city buildings, as well as the surrounding natural environment, landscape, vegetation, and water bodies, among others to ensure the integrity of the restored objects. By consulting historical documents, archeological reports, research materials, and ancient maps, among other information, relevant information on the city site and surrounding environment can be obtained, and the historical development, changes, and characteristics of cultural architecture and natural elements can be extracted. Field research was conducted on the target environment for urban heritage site restoration, and a comprehensive point cloud model and aerial image of the object were obtained through drone photography. The current status of the restored object and the surrounding natural environment was obtained, and the general rules of the virtual reconstruction design of the ruins were summarized. Then, professional software was used to process the collected data, forming a measurable point cloud model that provided basic data for the next step of constructing a three-dimensional model.

Methods for virtual reconstruction design

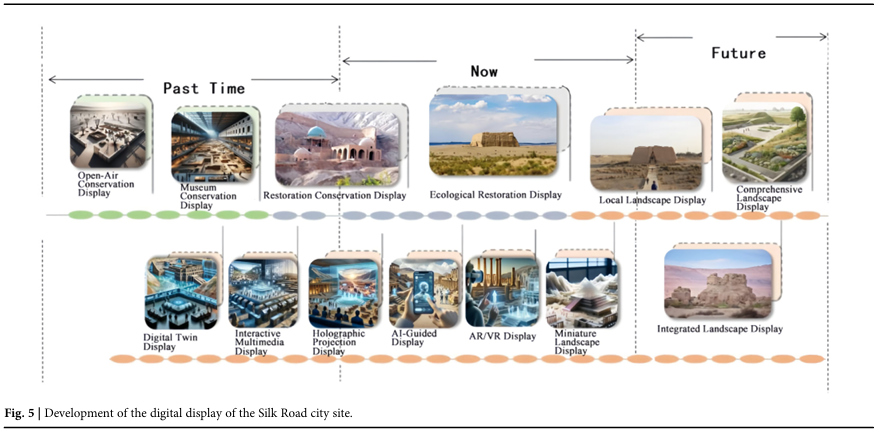

Virtual reconstruction technology can effectively help us restore the original appearance of the site. This provides a new restoration design option for Silk Road archeological sites (Fig. 5). Interactive 3D visualization and artificial intelligence (AI) technology, especially in the fields of data processing, 3D modeling, virtual reality, and intelligent prediction, can significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of archeological site virtual reconstruction. The damaged or broken landscape should be restored to enable the historical context of the Silk Road archeological sites to be recreated47,48,49.

Fig. 5

figure 5

Development of the digital display of the Silk Road city site.

Automated data processing and classification

Three-dimensional point cloud data obtained through technologies such as drone aerial photography constitute the foundation of restoration work. The point cloud data of the Suoyang city site typically contains millions to billions of data points, and AI algorithms can classify, denoise, and extract features from these data through deep learning techniques such as PointNet and PointNet++, helping us efficiently construct accurate 3D models. The restoration process can use PointNet + + to segment and classify point cloud data and extract elements such as walls, roads, and landscape structures50. The algorithm achieves effective data classification by learning the local geometric features present in point clouds. The optimization of point cloud data can be achieved through the following least squares method:

(1)

where

represents the coordinate of each point in the point cloud data and is the

optimized point. The goal is to minimize the point cloud data errors and ensure a highly accurate restored model.

By employing deep learning models, including autoencoders or regression networks based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), artificial intelligence (AI) can recreate the damaged parts of buildings and optimize existing models utilizing point cloud data.

Historical images of the ruins (such as archeological excavation photos and ancient paintings, among others) can be analyzed through image recognition technology to extract architectural details. The CNN algorithm is used to automatically annotate and classify building features in images, further improving the 3D model. The image feature extraction formula for CNN-based feature extraction can be expressed as follows:

(2)

where x is the input image data, W is the weight matrix of the convolutional layer, b is the bias term, f is the activation function, and y is the output feature. Through this network, AI can identify key structural features of the buildings at the Suoyang city ruins, such as the shape of the city walls and the decorative elements of the city gates.

We employed a convolutional neural network (CNN) model to extract and classify architectural features from historical excavation images and archival photographs.

① Training Data: A total of 300 annotated historical images were collected from excavation archives and academic publications. These included photos of wall fragments, gates, piers, and earth mounds with archeological annotations.

② Labeling process: Six architectural categories were defined (e.g., wall segment, tower base, gate frame, pier, foundation, and erosion trace). Annotations were verified by two domain experts.

③ Model architecture: We used a modified VGG-16 architecture with an input size of 224×224 pixels and cross-entropy loss.

④ Training details:

Epochs: 50

Batch size: 16

Optimizer: Adam (lr = 1e-4)

Accuracy achieved on the validation set: 92.8%

⑤ Output Use: The output segmentation maps were used to texture and geometrically adjust the 3D model of the site of Suoyang city.

3D modeling and restoration

In the virtual reconstruction design of archeological ruins, the role of AI is not limited to data processing but also includes the generation and optimization of restoration models. By utilizing deep learning techniques such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), it is possible to generate and optimize restoration models for archeological ruins that can reconstruct the damaged parts of the ruins. GAN modeling is a technique that generates high-quality images through adversarial training. In the virtual reconstruction of the Suoyang city ruins, GANs can generate parts that match the historical style of the existing architectural parts of the ruins. When applying GANs, the generator attempts to create realistic images, whereas the discriminator determines whether these images match the true historical style. After multiple rounds of adversarial training, the generator is able to generate building models that match the actual context of the ruins. The loss function of a GAN can be expressed as follows:

(3)

where x is the actual historical data, z is the random noise input of the generator, D is the discriminator, G is the generator, PDATA is the true distribution of historical data, and Pz is the distribution of random noise. The goal is to minimize the discriminator’s erroneous judgments on the generated model so that the images generated are as similar as possible to the actual ruins.

In addition to generating missing parts, GANs can also optimize the details of existing models (such as brick and stone structures and cave sculptures) to make the restoration effect more realistic.

A generative adversarial network (GAN) was utilized to reconstruct missing architectural components where physical remains were incomplete or missing.

① Training Data: Five hundred image patches of Tang dynasty architectural forms and 3D renderings from historical reconstructions were used.

② Architecture: The GAN consists of a U-Net-based generator and a PatchGAN discriminator.

③ Training Objective: To generate high-fidelity 2D architectural elements that resemble the stylistic conventions of the Han and Tang dynasties.

④ Output Samples: The results generated by the model are presented through representative examples and qualitative comparisons with archeological sketches, demonstrating the fidelity of the reconstructed forms and their consistency with historically documented typologies.

⑤ Expert evaluation: Three heritage architects evaluated the outputs and confirmed the stylistic validity of the images produced in 87% of the cases.

GAN training hyperparameters and losses

We train the conditional U-Net/PatchGAN with AdamW (β₁ = 0.5, β₂ = 0.999), initial lr = 2 × 10−4 and cosine decay to 2 × 10−5 after 100 epochs, batch = 8, for up to 200 epochs with early stopping (patience = 15, criterion: validation L1 + LPIPS). The generator objective is

(4)

using hinge adversarial loss, Charbonnier reconstruction, a VGG-19 (relu_3_3) perceptual term (LPIPS for validation), an edge loss on Sobel gradients, and mild TV regularization, with weights λ_adv = 1.0, λ₁ = 100, λ_perc = 10, λ_edge = 1, λ_tv = 1 × 10−4. The discriminator adopts spectral normalization. We apply gradient clipping (1.0 global-norm), EMA = 0.999 for the generator, and mixed-precision training; the best checkpoint is selected by the lowest composite validation loss.

Conditional inputs for generative inference

The GAN is implemented in a conditional image-to-image regime in which generation is guided by a multi-channel tensor assembled from the survey and segmentation pipeline. For each target area, conditioning comprises: (i) context RGB produced as orthographic renders/ortho-photomosaics over the scan-derived base model; (ii) a binary occupancy/missing-region mask identifying low-confidence or eroded zones; (iii) a distance-to-boundary field to stabilize inpainting near edges; (iv) an edge/silhouette map derived from the context render and scan-projected guide curves (e.g., wall centerlines, arch trajectories); and (v) a one-hot semantic map indicating the element class (e.g., wall segment, gate frame, pier/tower base, foundation), with class labels provided by the upstream point-cloud segmentation (PointNet + +) cross-checked against an image-based CNN classifier. The model does not employ textual embeddings.

During training, all conditioning channels are computed from paired samples built by masking annotated, scan-aligned imagery; optimization combines adversarial and reconstruction losses with an edge-aware term to preserve structural lines. At inference, the same channels are constructed automatically from the survey pipeline: context RGB from orthographic UV renders, masks from the project’s confidence map and QA flags, edges from the context render plus guide curves traced on the point cloud/mesh, and semantics from PointNet++ verified by the CNN classifier. Patches are processed with overlap-tiling and multi-scale passes (×0.75, ×1.0, ×1.5), then blended prior to 2D-to-3D lifting (see “GAN output representation and 3D integration”). All conditioning inputs and parameters are recorded as paradata; generated regions inherit the study’s confidence coding and are rendered with recognizability cues to distinguish measured from inferred content.

GAN output representation and 3D integration

In this study, generative inference is performed in 2D image space. The U-Net–based generator outputs orthographic 2D patches for target elements together with auxiliary maps (albedo/texture and displacement/normal maps). These 2D outputs are then constrained to the survey-derived base model (UAV/LiDAR mesh or TIN) via a two-step lifting procedure: (1) parametric profiling and extrusion/sweep along scan-tracked guide curves to obtain watertight volumes for walls, piers, and gate frames; and (2) displacement projection onto the local mesh to recover fine relief consistent with the predicted normal/displacement fields while preserving scan geometry (snap-to-scan constraint, collision checks, and non-shrink-wrap smoothing). For features that require thickness (e.g., arches and lintels), image-derived silhouettes are converted to planar splines and procedurally swept with thickness bounds taken from point-cloud cross-sections and historical dimensional ratios.

To integrate the generated geometry into the UAV/LiDAR site coordinate frame, each sector inherits an orthographic local frame unwrapped from the survey model; components are brought into the global system via control-point initialization (corners/edges) followed by rigid ICP, with optional local ARAP refinement when residuals exceed a tolerance. Conflicts with measured remnants are resolved by Boolean difference and snap-to-scan within an ε-threshold, with measured geometry taking precedence; dangling or interpenetrating faces are cleaned during post-processing. All generated components are tagged with the study’s confidence coding (measured/inferred / conjectural), recorded with paradata (input sources, model choices, parameters, expert review), and rendered with visual recognizability (semi-transparent or differentiated materials) to distinguish measured from inferred content. We did not employ native 3D generative models (voxels, point clouds, or implicit SDF/occupancy fields) in this work; such approaches are identified as future work for volumetric completion under the same transparency and uncertainty conventions.

Authenticity and transparency considerations

The application of generative adversarial networks (GANs) to reconstruct missing components necessarily engages with the authenticity debate in cultural heritage conservation. Since the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994)51, authenticity has been understood as encompassing not only material substance but also form and design, setting, traditions, and spirit and feeling. This view has been integrated into digital heritage practice through requirements for traceability, paradata, and recognizability, ensuring that all reconstructions clearly distinguish between measured, inferred, and conjectural content.

In the present study, these principles were applied by (1) annotating all generated elements within the 3D model as “conjectural reconstructions,” (2) archiving input datasets, model parameters, and output layers as paradata for reproducibility, and (3) visually differentiating reconstructed surfaces with semi-transparent textures in the VR environment. This approach aligns the restoration workflow with international transparency standards and avoids creating a “false sense of reality” in virtual reconstruction.

The combination of VR/AR

The restoration of archeological sites requires not only the presentation of two-dimensional images but also immersive experiences provided through the use of VR and AR technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI) can enhance interactivity, real-time performance, and accuracy during this process. Combining AI and VR technology can provide users with personalized virtual tours. Users can interact with virtual ruins through smart devices and can inquire about historical events and architectural information, among other information. AI provides real-time voice or text feedback on the basis of user needs. Moreover, by using NLP models such as BERT or GPT, AI can understand users’ questions and provide accurate answers. For example, users can inquire about the historical background of the construction of a grotto, and AI will extract and generate historical data related to the question through deep learning models. By jointly optimizing speech recognition and text generation, the following formula can be used:

(5)

where x is the voice or text data input by the user, θ is the model parameter, and y_hat is the AI-generated answer.

We applied a BERT-based NLP model (BERT-Base Chinese) to extract spatial and semantic knowledge from ancient historical texts and archeological records.

A dataset of ~50,000 Chinese characters was assembled from classical texts, excavation reports, and site notes related to Suoyang city and other Silk Road ruins.

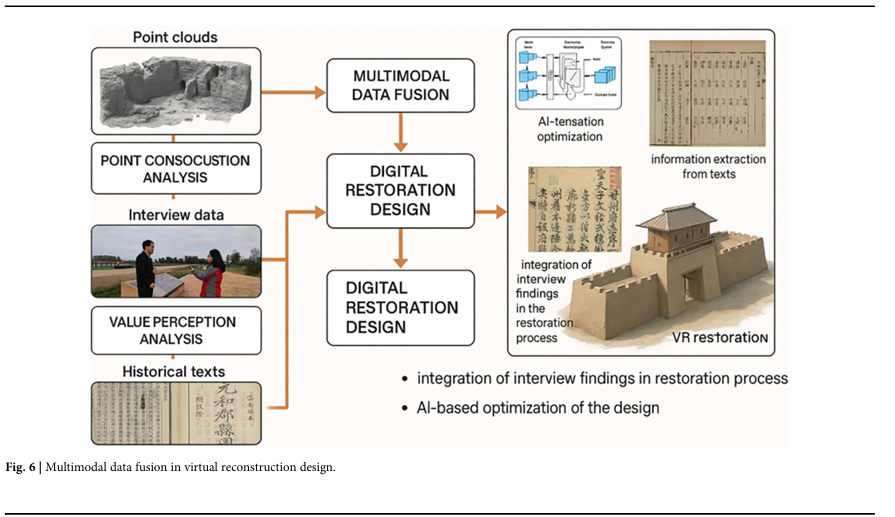

Through the use of AR technology, users can observe a virtual restoration model of the Suoyang city site in the real world and interact with it. For example, through mobile phones or AR glasses, users can see restored elements such as city walls and buildings in the real environment.This logic is visualized in Fig. 6 and Table 1, which outlines the full workflow from data acquisition to immersive VR deployment.

Fig. 6

figure 6

Multimodal data fusion in virtual reconstruction design.

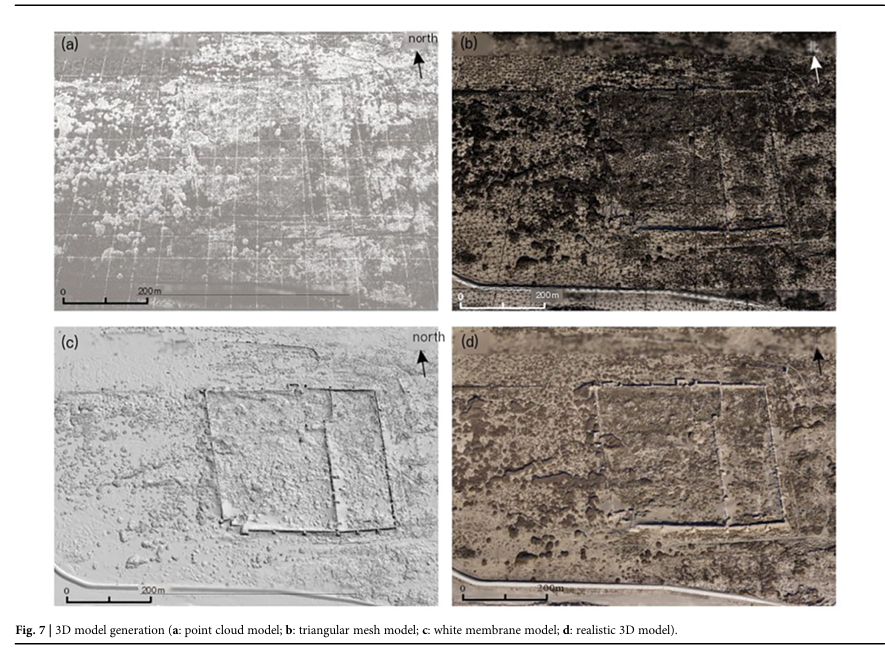

Table 1 Multimodal data types and their integration in the restoration workflow

Historical data mining and reasoning

The restoration of the remains not only relies on modern technology but also requires the full utilization of archeological and historical research content. AI, through natural language processing (NLP) technology, can analyze and make inferences based on a large number of historical documents and archeological reports, thus supplementing the shortcomings of ruin restoration. AI can interpret archeological documents and inscriptions related to the Suoyang city site through natural language processing techniques such as BERT, extracting information related to architectural style, function, and historical background. These pieces of information can be used to further speculate on the structure and purpose of the ruins. The following text analysis formula is based on deep learning models:

(6)

where X is the input historical text data, and H is the hidden layer representation generated by BERT for subsequent entity recognition and information extraction.

In addition to extracting known information, AI can also make inferences about unknown parts on the basis of the historical literature. By constructing a knowledge graph, other possible features or structures of the site can be inferred on the basis of existing historical data.

Intelligent prediction and restoration optimization

The restoration design of the site must also consider its protection and conservation. The established predictive model can help analyze the damage trends of future sites and optimize restoration strategies. Through machine learning algorithms such as decision trees and random forests, artificial intelligence (AI) can intelligently optimize restoration plans on the basis of the damage historical remains have incurred, ensuring the scientific and efficient nature of restoration work.

Genetic algorithm optimization

The genetic algorithm is an intelligent optimization algorithm that simulates the process of biological evolution in nature, gradually optimizing problem solutions through genetic operations such as population selection, crossover, and mutation. Optimizing design parameters to achieve a balance between historical matching52, structural stability, and visual consistency is a key task in the virtual reconstruction design of archeological sites. This study combines the virtual reconstruction design method proposed in the previous section with the genetic algorithm (GA), which is used as an intelligent optimization tool for multiobjective optimization of restoration design variables.

① Define the design variables and objective functions

When the genetic algorithm is applied to the restoration design of the Suoyang city site, the main optimization variables include the following:

h: City wall height (range 3.0–6.5 meters)

w: City gate width (range 8.0–14.0 meters)

l: City gate thickness (range 4.5–6.0 meters)

p: Oasis vegetation coverage rate (ranging from 20% to 70%)

The purpose of the objective function is to maximize the overall effectiveness of the design scheme, including the following three main indicators: historical accuracy, structural stability, and visual consistency.

The objective function is defined as the weight of each indicator

W1: = 0.4

W2: = 0.3

W3: = 0.3

Assuming the logic of functions g1, g2, g3 (only illustrated here)

= Historical matching degree calculation logic

= Structural stability calculation logic

= Visual consistency calculation logic

Objective function

(7)

where g1 is the historical matching degree; g2 is the structural stability; g3 is the visual consistency; and W1, W2, W3 are the weights of each indicator (adjustable, such as W1 = 0.4, W2 = 0.3, W3 = 0.3).

② Initial design proposal set

The scheme set includes multiple initial design schemes, each of which is randomly assigned variable values:

(8)

where Xi = (hi, wi, li, pi) is the i-th design scheme, and n is the size of the scheme set (such as 50 schemes).

③ Evaluation of the pros and cons of the plan

The advantages and disadvantages of each design scheme are evaluated to assess its strengths and weaknesses, and the formula is as follows:

(9)

The higher the fitness value is, the better the design scheme.

④ Optimize operations

Using the roulette wheel selection method, a design scheme based on fitness values is randomly selected for the next operation. The probability of selection is as follows:

(10)

⑤ Scheme combination

Generate new design schemes through scheme combinations. Using the single-point crossover method, two options are randomly selected:

(11)

(12)

Swap on any variable, for example, as follows:

(13)

(14)

⑥ Scheme adjustment

Randomly adjust a variable in the design scheme with a certain probability. Assuming that the mutation probability is Pm, the mutation formula is as follows:

(15)

where r is a random number from -1 to 1 and where Δ is the range of variable variation (e.g., Δ h = 0.5).

⑦ Iteration Optimization

The selection, crossover, and mutation operations are repeated until the maximum number of iterations is reached or the optimal solution is found. The optimization process is as follows:

The fitness of each generation population is calculated, and the best design solution is selected. If the fitness value no longer significantly improves, the iteration process stops. The input conditions of the application are as follows: initial scheme size: 50; maximum number of iterations: 100; combination probability: 0.8; and adjustment probability: 0.1.

During the optimization process, the initial generated solution is as follows:

(16)

where h = 4.2 meters; W = 12.0 meters; L = 5.0 meters; and p = 40%. The objective function value f (X) and fitness value Fitness (X) are calculated; individuals with high adaptability are selected to enter the next generation. After 100 optimization generations, the optimal solution is as follows: h = 5.8 meters; W = 13.2 meters; L = 5.5 meters; and p = 65%. The optimization results are as follows: the degree of historical matching has improved to 90%; the structural stability has improved to 85%; and the visual consistency has improved to 92%.

As shown in Eq. (15), the genetic algorithm can be used to determine the most plausible combination of wall height, gate proportions, and vegetation density. These optimized values were directly applied to guide the digital modeling of site structures and environmental restoration.

Results

Generation of a 3D model of Suoyang city site

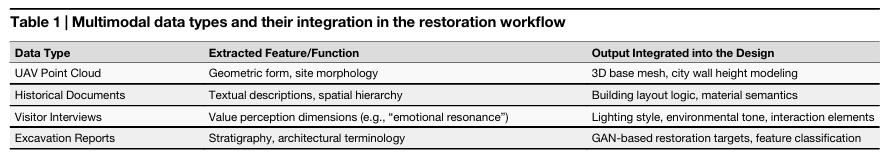

The research team conducted field research at the Suoyang city site from December 15th to 18th, 2023, and from August 16th to 18th, 2024. A DJI M210 unmanned aerial vehicle and onboard camera, with a sensor size of 23.5 mm × 15.6 mm, a single lens resolution of 6000 × 4000, and a pixel size of 3.9 μm, were used for the aerial survey. Through the use of drone oblique photography technology, comprehensive information on the heritage site and its surrounding environment in Suoyang city was obtained through an onsite survey and data collection. The process of generating a 3D model of a drone is as follows: on the basis of dense matching of multiview images, a 3D high-density point cloud model is first generated (Fig. 7a). On the basis of the 3D point cloud, a triangular mesh (TIN) model image can be generated (Fig. 7b), which is then encapsulated to form a white film model (Fig. 7c). After texture mapping, the real scene is finally generated (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 7

figure 7

3D model generation (a: point cloud model; b: triangular mesh model; c: white membrane model; d: realistic 3D model).

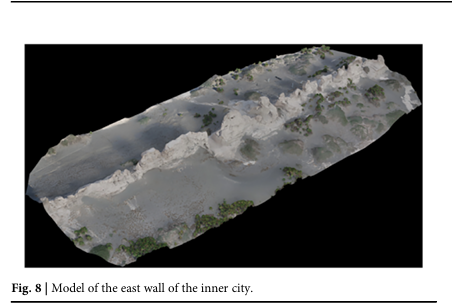

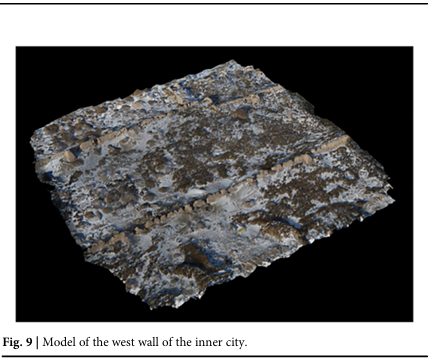

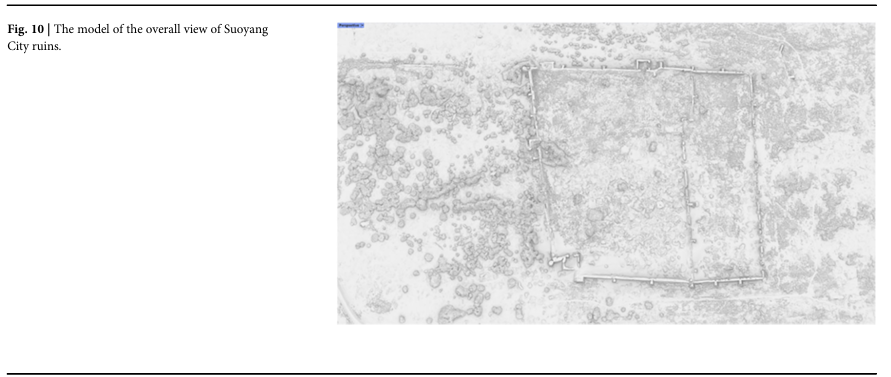

Three different scales and accuracies of three-dimensional models were established for the Suoyang city site, including a model with a scale accuracy of approximately 1 cm for the inner city east wall Section 02 at a scale of 150 meters by 50 meters (Fig. 8), a model with a scale accuracy of approximately 5 cm for the inner city east wall and inner city partition wall at a scale of 350 meters by 350 meters (Fig. 9), and a model with a scale accuracy of approximately 10 cm for the entire city of Suoyang at a scale of 1600 meters by 800 meters (Fig. 10).

Fig. 8

figure 8

Model of the east wall of the inner city.

Fig. 9

figure 9

Model of the west wall of the inner city.

Fig. 10

figure 10

The model of the overall view of Suoyang City ruins.

By comparing the aerial view of the Suoyang city site surveyed by drones with the archeological topographic map, the results show that the overall layouts of the two are highly consistent. Moreover, important nodes within the site of Suoyang city, such as the city wall structure, ancient roads, tomb groups, and military facilities, are marked to provide intuitive reference data for the restoration process, accurately reflecting the spatial layout and functional structure of Suoyang city during its historical period.

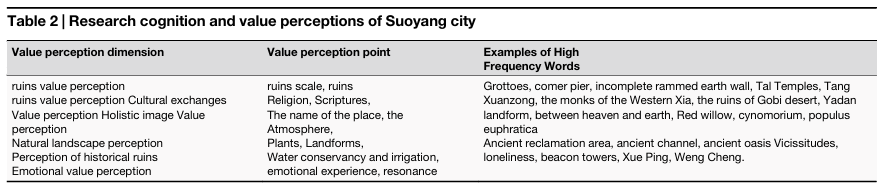

Value perception analysis of sites

The research team conducted two surveys and effectively interviewed 40 tourists. The 40 tourists were selected using a purposive sampling strategy aimed at capturing a wide range of perspectives among domestic visitors to the Suoyang City site. The selection was conducted onsite over a three-month period from August to October 2023, covering both peak tourism (summer holidays) and normal visitation periods. The researchers approached visitors at designated rest areas, explained the study, and invited them to participate on a voluntary basis. The onsite interviews were conducted at three key spatial nodes within the Suoyang city site to capture context-specific visitor perceptions: (1) the eastern city gate platform, where most visitors begin their tour; (2) the central plaza near the remains of the Buddhist pagoda, which serves as a common resting area and vantage point for viewing religious structures; and (3) the northern earthen wall perimeter, which provides panoramic views of the surrounding landscape and invites broader spatial reflection on the heritage site’s configuration. The interview content mainly included the following questions: “How did you learn about Suoyang city site? What feelings did you experience and benefits did you receive during the visit to Suoyang city site?” “What impressed you the most about Suoyang city site?” “What do you think the value of the large ruins is reflected in? What impact does the greening and landscape of Suoyang city site have on unlocking the city site?” “Will you continue to pay attention to Suoyang city site and its protection and development in the future?” “What do you think is the first focus of the Suoyang city site restoration project?” and “Briefly describe your personal travel experience”. The interview time ranged from 15 min to 45 min. The main focus of online information collection was online travel webruins, and online comments and travelogues were collected as supplementary materials for analyzing the perceptions of the Suoyang city site. Considering that the Suoyang city site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage cultural site in 2014, we collected online comments and travelogues posted between 2015 and 2022 from widely used platforms such as Mafengwo, Weibo, Ctrip, and TripAdvisor. After rigorous screening, a total of 100 valid textual records were selected for content analysis(Table 2, Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

figure 11

Suoyang city site travel notes 100 high-frequency words.

Table 2 Research cognition and value perceptions of Suoyang city

Correlation analysis between value perception and restoration factors

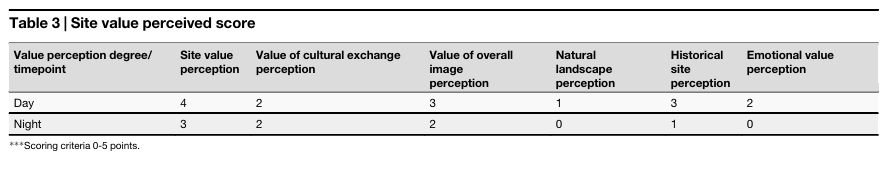

On the basis of the dimension of value perception, a quantitative analysis system for value perception was constructed to scientifically analyze and quantify the obtained data. The system covers six indicators, namely, “site value perception”, “cultural exchange value perception”, “overall image value perception”, “natural landscape perception”, “historical relic perception”, and “emotional value perception”, to more comprehensively capture the site value perception characteristics of the Suoyang city site during the day and night (as shown in Table 3).

Table 3 Site value perceived score

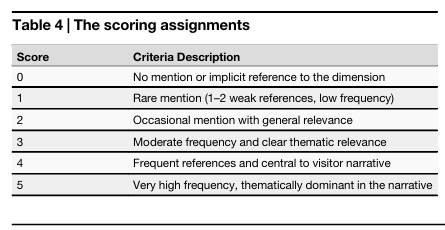

Each dimension was assessed on the basis of the frequency and semantic weight of high-frequency keywords that appeared in both in-person interviews (n = 40) and online user-generated content (n = 100). The scoring was assigned as follows (Table 4):

Table 4 The scoring assignments

Analysis of value perception and restoration factors

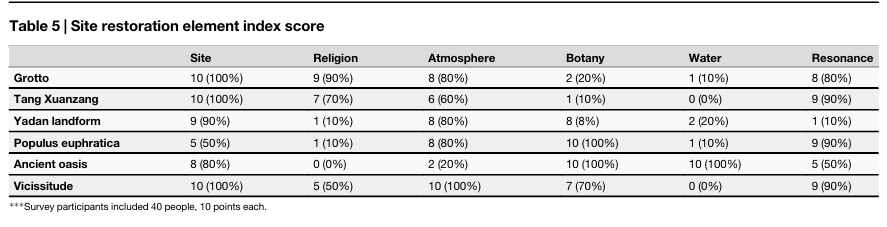

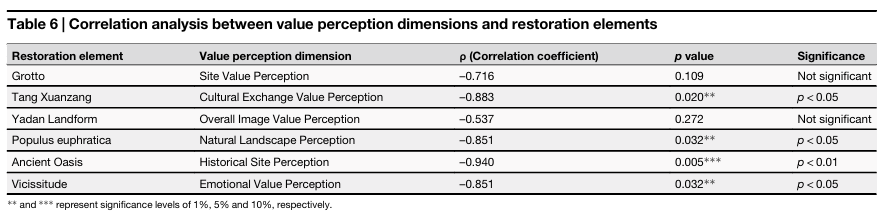

By extracting the characteristics of visitors’ value perception points and analyzing high-frequency keywords across different areas of the Suoyang city archeological site, six representative elements were identified to inform the restoration design: Grotto (ancient Buddhist cave remains), Tang Xuanzang (cultural link to the monk’s historic journey), Yadan landform (distinct desert rock formations), Populus euphratica (native desert poplar trees), Ancient oasis (historic water sources and farmlands), and Vicissitude (weathered structures symbolizing the site’s historical changes). During the field research, 40 tourists were interviewed in depth, and the high-frequency word score rate was calculated. The data were calculated and expressed on the basis of the POI data marked in the map, making the research results more convincing and credible (see Table 5 for the results).

Table 5 Site restoration element index score

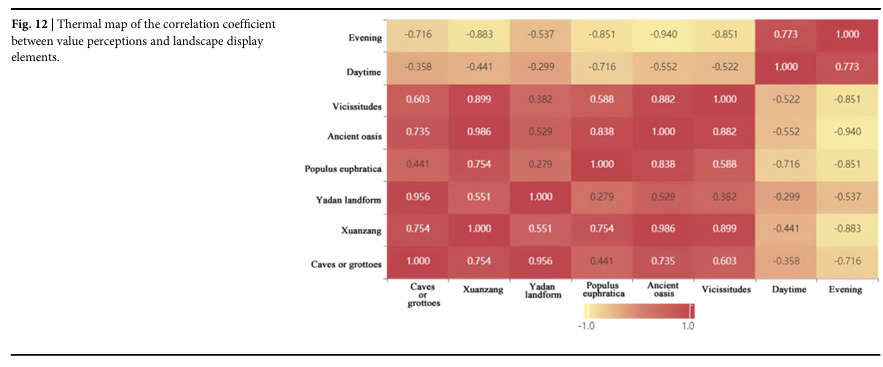

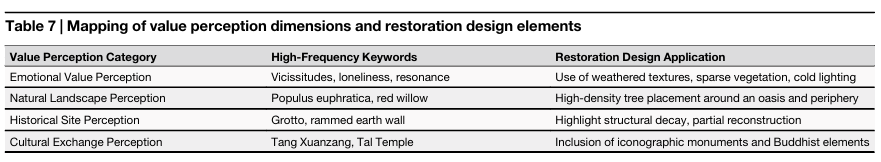

By using the SPSS platform, Spearman correlation analysis, the correlation strength between value perception and indicators of site restoration elements was determined during the day and night. The results revealed that high-frequency words such as “grotto” were negatively correlated with site value perception, “Tang Xuanzang” was negatively correlated with cultural exchange value perception, “Populus euphratica” was negatively correlated with natural landscape perception, “ancient oasis” was negatively correlated with historical relic perception, and “vicissitudes” was negatively correlated with emotional value perception during the day and night, with a particularly prominent correlation observed at night. The perception of the overall image value of the Yadan landform was negatively correlated during the day and night, with weak significance. Other correlation coefficients are shown in Tables 6, 7 and Fig. 12.

Fig. 12

figure 12

Thermal map of the correlation coefficient between value perceptions and landscape display elements.

Table 6 Correlation analysis between value perception dimensions and restoration elements

Table 7 Mapping of value perception dimensions and restoration design elements

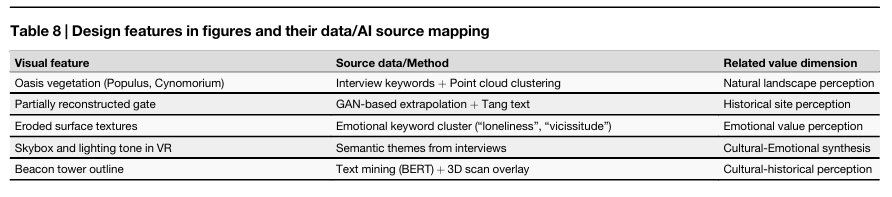

Multimodal data fusion in virtual reconstruction design

The virtual reconstruction of Suoyang city relies not only on advanced modeling techniques but also on the effective integration of heterogeneous data sources, including spatial data (point clouds), semantic data (historical texts), and cognitive-perceptual data (visitor interviews). This study constructs a multimodal data fusion framework to guide restoration decisions and ensure that both historical authenticity and perceptual relevance are represented in the final design Table 8.

Table 8 Design features in figures and their data/AI source mapping

1. Spatial Data Layer: UAV and 3D Laser Scans

High-resolution point cloud data, obtained through UAV oblique photography and terrestrial 3D laser scanning, serve as the geometric basis for the restoration. These datasets define the foundational terrain, wall remnants, gate locations, and structural contours of Suoyang city. The three-dimensional accuracy achieved (ranging from 1 cm to 10 cm) allows for precise geometric modeling.

2. Semantic Data Layer: Historical Documents and Excavation Reports

Historical archives, classical Chinese texts, and archeological reports were processed using BERT-based natural language processing models to extract references to the city layout, material descriptions, and functional zones (e.g., “outer gate,” “watchtower,” or “oasis”). These semantic entities were georeferenced and aligned with spatial coordinates from the point cloud, forming a layered annotation over the base model. For example, mentions of “corner piers” or “partition walls” were used to verify and adjust the structural reconstructions in the VR model.

3. Perceptual Data Layer: Visitor Value Perception

A total of 40 structured interviews and 100 user-generated travelogues were analyzed using KH Coder for high-frequency word extraction and co-occurrence analysis. The results were grouped into six value perception dimensions (e.g., emotional, cultural, and ecological). These dimensions were quantitatively scored and mapped onto spatial elements of the site to identify perception “hotspots” and inform the emotional layering of the restoration (e.g., using lighting, sound, or material aging effects).

4. Design Logic

The integration process follows a three-step fusion logic:

Step 1: Geometric anchoring – Use point cloud data to establish the physical structure.

Step 2: Semantic enrichment – Overlay historically derived attributes (e.g., gate forms or structural ratios) onto the 3D mesh.

Step 3: Experiential prioritization – Value perception analysis is applied to prioritize visual, atmospheric, and interactive features that align with visitor expectations.

5. Cross-Modal Example

For example, eastern city gate restoration was guided by UAV scans (to define physical dimensions), textual descriptions of the Tang dynasty (to infer arch curvature), and visitor interviews (which ranked the gate as a key symbolic feature under “historical site perception”).

The fusion of these sources ensured that the final digital model was not only technically accurate but also emotionally resonant and cognitively legible to contemporary viewers.

Virtual reconstruction design

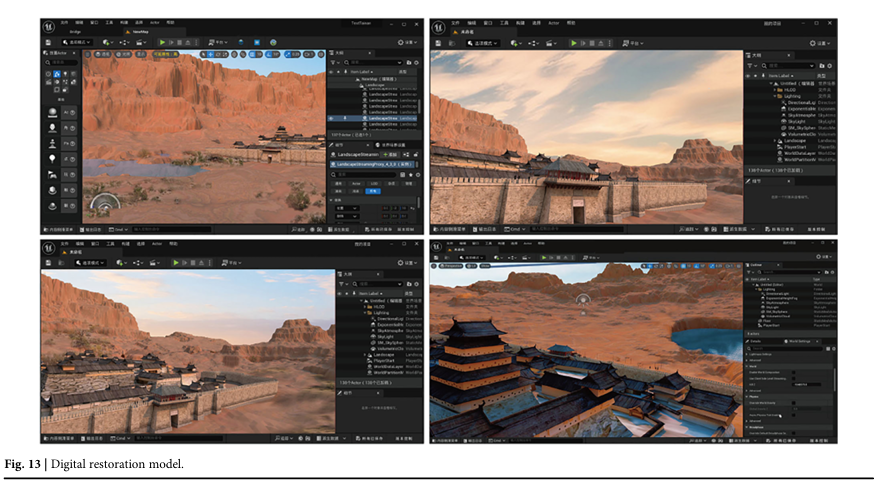

The virtual reconstruction design of Suoyang city is based on the archeological literature to display the layout and shape of the city site due to the scarcity of relevant archeological images. Relying on textual descriptions in archeological reports combined with photos and archeological maps from field investigations as prototypes, AI technology and AR/VR are used to achieve the digital restoration design. On the basis of the proportion of data provided in the archeological report, the morphological restoration design of the Suoyang city site was completed, thus presenting the unique design style of the Silk Road city sites. The specific steps for restoration design of the Suoyang city site include the following51: (1) reconstructing the terrain of Suoyang city on the basis of elevation maps; (2) clearly identifying the locations of key nodes for high-frequency cultural restoration, such as roads, beacon towers, grottoes, city gates, city walls, and oases, within city relics; (3) using AI technology to refine the design of contextual nodes; (4) restoring other facilities within city ruins; and (5) restoring the vegetation landscape around the site In the digital restoration design, we considered the following aspects on the basis of visitor perceptions: emotional terms such as “desolation”, “resonance”, and “silence” influenced the lighting design, skybox tone, and texture fading; high scoring in “natural landscape value” led to increased vegetation density, especially around the reconstructed oasis; and “historical site value” informed the decision to partially preserve rather than fully reconstruct certain walls, maintaining a sense of authenticity. Specifically, in Figures 13, the wall height and gate opening dimensions were optimized using a genetic algorithm, which adjusted the structural parameters on the basis of historical proportional data and construction principles inferred from point cloud analysis. In addition, the high-frequency keywords identified through BERT-based semantic analysis directly informed the restoration environment. For example, for the natural landscape perception dimension, words such as Populus euphratica and red willow guided the placement of high-density trees and vegetation patches around the oasis and city periphery.The emotional value perception category—keywords such as vicissitudes and loneliness—led to the use of weathered surface textures, sparse vegetation, and cooler lighting schemes to evoke a sense of historical passage.

Fig. 13

figure 13

Digital restoration model.

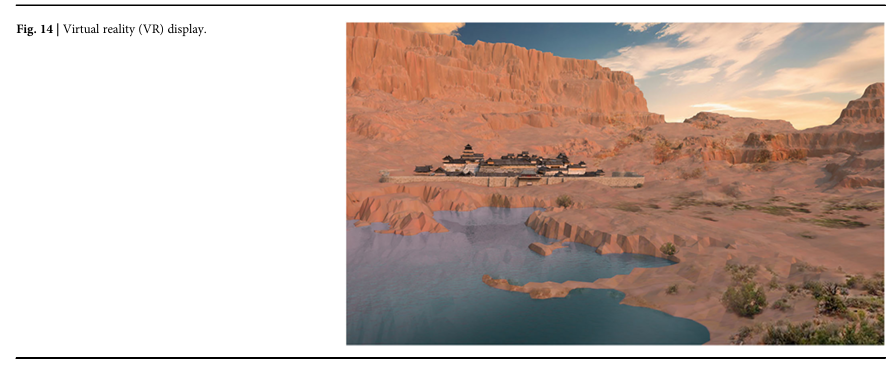

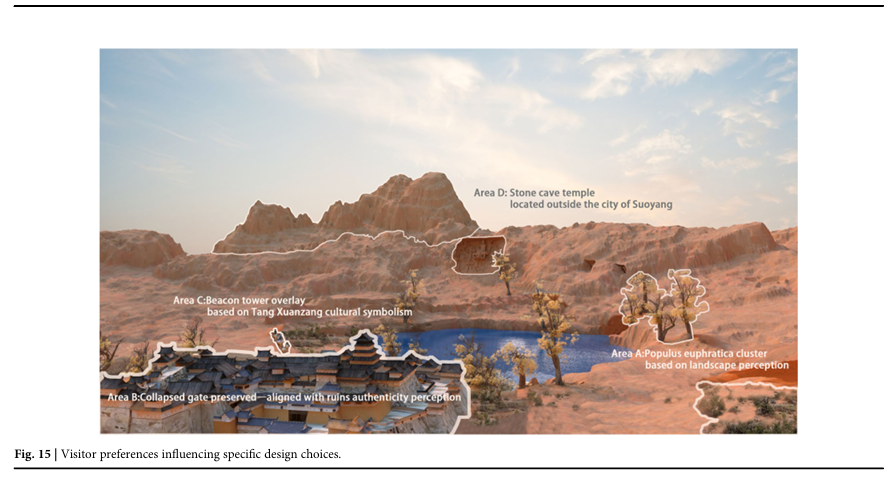

On the basis of the onsite environmental model and archeological data, AI and AR/VR technologies were used to digitally restore the representative landscape elements and high-frequency value perception elements of Suoyang city. The design results are shown in Fig. 14 and Fig.15. The completed model can be imported into VR devices (i.e., Unreal engine) to achieve a VR display of the Suoyang City site.

Fig. 14

figure 14

Virtual reality (VR) display.

Fig. 15

figure 15

Visitor preferences influencing specific design choices.

Discussion

This research aims to digitize the restoration design strategy of the Suoyang city site and proposes a restoration path based on multimodal data integration, starting from the correlation between archeological site value perception and restoration elements. The practical achievements and innovative methods of this research are highly important and reveal some areas that need further research and improvement.

This study explored the compatibility between restoration design and value perception. Through tourist interviews, value perception analysis, and the extraction of restoration elements, the perception dimensions are transformed into specific restoration design indicators. The research has shown that different value perceptions, such as cultural exchange, natural landscapes, and emotional resonance, have different focuses on the remaining restoration elements. For example, “emotional value perception” emphasizes the sense of vicissitudes and historical weight of the remains, whereas “natural landscape perception” focuses more on ecological elements such as oases and poplar trees. This correlation analysis provides a theoretical basis for restoration design, but in practical operation, how to simultaneously meet diverse perceptual needs and balance the relationship between historical authenticity and modern experience remains a challenge. We acknowledge that the interview sample size (n = 40), while sufficient for qualitative thematic saturation, is relatively small for quantitative generalization. Although supplemented by 100 user-generated reviews, the findings remain context-dependent and may not be fully representative of broader visitor populations or cross-cultural perceptions. The mapping from value perception dimensions to design decisions is inherently interpretive.

Figure 6 exemplifys how our restoration strategy translates multimodal data—point clouds, textual archives, and perception interviews—into unified spatial, atmospheric, and material design outputs. The application of AI techniques not only facilitated restoration geometry but also enabled perceptual alignment with visitor expectations, achieving a synthesis of technical fidelity and cultural resonance.

This study highlights the advantages and limitations of applying AI technology to site restoration design. This article employs artificial intelligence (AI) technology for deep processing and analysis of 3D point cloud data and archeological images, significantly improving the efficiency of data processing and the accuracy of restoration models. However, there are still limitations. First, there is a certain degree of uncertainty in predicting and repairing incomplete data, and automatic inference on the basis of existing data requires more historical literature and multimodal data supplementation. Our modeling is constrained by the availability and quality of historical documentation. Although the CNN and GAN models were validated for performance, their internal decision processes remain nontransparent, limiting interpretability. Second, the collaborative utilization of multimodal data has achieved the integration of point cloud, image, and text data, but there is still room for optimization in deep association mining between different modalities. Third, enhancing the perceived value of the tourist experience and how to use AI to generate restoration content suitable for different types of tourists’ interests and knowledge backgrounds are key directions for future improvements in display technology.

This study reveals the display potential of virtual reality/augmented reality (VR/AR) technology. The application of VR/AR technology in restoration design enhances the interactivity and immersion of site displays, allowing visitors to intuitively feel the historical atmosphere and spatial features of the ruins. However, there are also limitations in terms of device popularization and technological barriers in this research. Currently, VR/AR devices have high costs and complex technologies, making it difficult to apply them on a large scale to site display scenarios. While we present a VR-integrated model informed by perception analysis, we did not conduct formal usability testing or measure long-term user engagement and learning outcomes. Future research should evaluate how different perception design strategies impact user interpretation, memory retention, and heritage empathy through controlled studies. Content update and maintenance: Digital content needs to be regularly updated to maintain the scientific and cutting-edge nature of historical restoration, which places greater demands on resources and manpower. Multiple types of sensory integration: At present, displays focus mainly on visual experiences, and in the future, the integration of auditory, tactile, and even olfactory senses can be explored to enhance immersive effects.

The smooth implementation of digital restoration design for the Suoyang city site relies on deep collaboration in multiple fields, such as archeology, architecture, history, and computer science. However, there are differences in research objectives, technical language, and evaluation criteria among different disciplines. In the future, it will be necessary to strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration mechanisms and promote the integration of diverse knowledge.

While the study did not adopt a formal hypothesis-testing design, it provides empirical support for two key interpretive hypotheses. First, the emotional and symbolic dimensions of visitor perception—such as perceptions of authenticity, sacredness, and desolation—can directly inform spatial modeling and restoration decisions. Second, the fusion of multimodal data (point clouds, GAN/CNN outputs, BERT-analyzed texts, and visitor interviews) can yield more culturally resonant and perceptually aligned digital reconstructions. These findings contribute to the growing literature that seeks to bridge computational modeling with affective heritage interpretation.

Although this study did not employ a formal hypothesis-testing design, it offers interpretative insights that may inform potential hypotheses regarding perception and value for future empirical testing.

First, the emotional and symbolic dimensions of visitor perception—such as authenticity, sacredness, and desolation—can inform spatial modeling and restoration decisions.

Second, the integration of multimodal data (point clouds, GAN/CNN outputs, BERT-analyzed texts, and visitor interviews) appears to enhance cultural resonance and perceptual alignment in digital reconstructions.

These theoretical directions emerging from this study contribute to the ongoing discourse that seeks to bridge computational modeling with affective heritage interpretation.

This study analyzes the relationship between the perceived value of the site and its node element indicators. It employs drone-based oblique photogrammetry to analyze the spatial layout and key node characteristics of the Suoyang city site, proposes a systematic digital restoration framework and workflow, and integrates AI with VR/AR technologies to support the digital restoration design of this heritage site, providing reference and guidance for heritage restoration research in the digital age. The following conclusions are drawn:

A digital restoration design framework based on a multimodal data-driven approach is proposed in this study. By integrating drone-based oblique photogrammetry, 3D laser scanning, and AI technologies, a high-resolution three-dimensional model of the Suoyang city site was constructed. This enables precise digital comparison with existing archeological surveys and facilitates the identification and classification of key structural nodes, such as city walls, ancient roads, tomb clusters, and military installations. The framework more accurately represents the site’s spatial layout and functional zoning, providing robust reference data for restoration planning. Moreover, value perception analysis and element extraction were applied to these structural nodes, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional restoration methods in terms of data integration and accuracy control and offering new insights for the restoration of similar heritage sites.

Value perception-driven restoration methods. On the basis of value perception analysis, this study revealed the correlation between tourists’ perceptions and the elements of site restoration and, on the basis of this, constructed restoration design principles centered on value identification and emotional resonance. This perception-oriented restoration method not only enhances the scientificity of restoration design but also enhances tourists’ cultural identity and site experience.

Breakthrough applications of artificial intelligence technology. The application of AI technology in the digital restoration of the Suoyang city site provides strong support for the classification of point cloud data, image feature extraction, and model generation and optimization. Moreover, the integration of AI with virtual reality technologies enables dynamic visualization and personalized interaction for site restoration, significantly enhancing the immersion and usability of digital heritage presentations.

Research has demonstrated that VR and AR technologies hold significant promise for the restoration and presentation of archeological sites. Through immersive virtual and augmented reality experiences, visitors can engage deeply with the historical context of heritage sites and develop a stronger sense of identification with preservation efforts. However, further improvements are needed in terms of technological accessibility, multisensory interaction, and timely content updates to fully realize the potential of these digital tools. Consistent with the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994), this study also acknowledges that digital reconstruction should maintain transparency and cultural contextualization, ensuring that conjectural elements remain explicitly recognizable and traceable. By operationalizing layered evidence visualization, confidence coding, and transparent paradata documentation, the study ensures that uncertainty is not minimized but made explicit—transforming generative reconstruction into an accountable, evidence-linked interpretative process consistent with the ethical standards of virtual heritage practice.

Data availability

Data are available on request to the corresponding author.