书籍资料库

石语梵行 |《英国伦敦维多利亚与阿尔伯特博物馆对犍陀罗灰泥佛像头的调查》2019年

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Giovanni Verri, Christian Luczanits, Victor Borges, Nick Barnard et John Clarke

本研究展示了在伦敦维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆举行的犍陀罗重要头像的技术和历史研究结果。多年来,这件作品因其极高的审美品质而在犍陀罗艺术史上占有重要地位。然而,自 1930 年代在博物馆展出以来,它几乎没有被科学地研究过。为了研究材料、博物馆和保护修复数据,增加了使用非侵入性非接触技术的结构分析:图像、IRTF 光谱(红外傅里叶变换光谱法),XRF(X射线荧光分析),FORS(使用光纤反射光谱法)。支撑由几层石灰石膏砂浆(混合石膏)组成。仅应用于主要面部特征(如嘴唇、眼睛)和头发的颜料分别是高品质的赭红色和不明黑色。对头部结构的仔细检查确定它可能属于佛陀的标志性代表,而不是叙事场景。

Cette étude présente les résultats d’une recherche technique et historique sur une importante tête du Gandhara conservée au Victoria and Albert Museum, à Londres. Cette œuvre occupe depuis des années une place éminente dans l’histoire de l’art gandharien en raison de sa grande qualité esthétique. Pourtant, elle n’a guère été étudiée scientifiquement depuis son exposition au musée dans les années 1930. Aux recherches sur les données matérielles, muséales et de conservation-restauration s’est ajoutée une analyse structurelle utilisant des techniques non-invasives hors contact : imagerie, spectroscopie IRTF (Spectrométrie infrarouge par transformée de Fourier), XRF (analyse par fluorescence X), FORS (Spectrométrie par réflexion à l’aide de fibre optique). Le support se compose de plusieurs couches de mortier chaux-platre (platre de gachage). Les pigments, appliqués uniquement sur les principaux traits du visage (tels que les lèvres, les yeux) et sur les cheveux, sont respectivement une ocre rouge de grande qualité et un noir non identifié. Un examen attentif de la construction de la tête a permis de déterminer qu’elle appartenait probablement à une représentation iconique du Bouddha, par opposition aux scènes narratives.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Introduction

The appearance of ancient stone sculpture in the Mediterranean, Central Asia and the India Subcontinent is often associated with pristine, unpainted surfaces, appreciated for their unblemished appearance. This is certainly the case for ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, which has been long praised for its whiteness. However, it is a well-known fact that ancient sculpture was generally painted and the Buddhist sculptures from the Gandharan region are not an exception. While most schist sculpture now appears “elegantly” uniform and grey, stucco sculpture, by nature more porous than schist, often retains traces of their original painted decoration. While the making of ancient Greek and Roman sculptural polychromy has been the subject of intense scholarly studies and fierce debates since at least the late 18th century, Gandharan sculptural polychromy has received limited attention. Only a handful of technical investigations exist on metal and schist sculpture, and on clay and stucco.

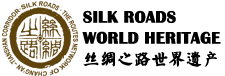

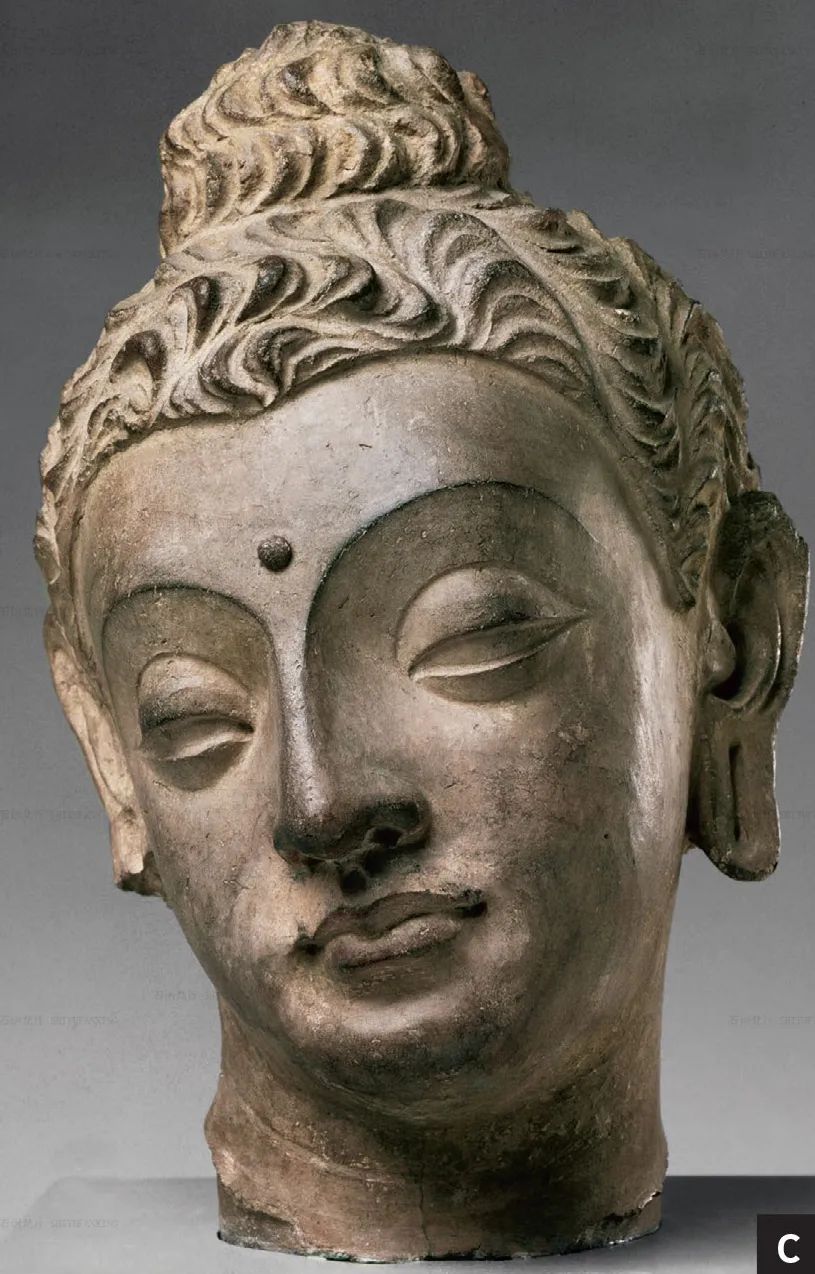

This paper focuses on the history, making and significance of a c. 4th-5th century stucco head in the Asian collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (IM.3-1931) and identifiable as the Buddha by the presence of lakshanas, or auspicious marks, such as the hair knot, or ushnisha, and the forehead mark, or urna. The presence of the elongated and pierced earlobes is an allusion to the Buddha’s former princely status, when he wore heavy pendant earrings (fig. 1 a). The head still retains traces of red colour on various areas, including the lips, the eyes, the philtrum and hairline. Small remnants of a black pigment can also be seen in the hair and above the upper lip. The materials and techniques used to create the head are studied using scientific techniques and placed within a wider archaeological/art-historical context, to provide further insights into its original appearance, provenance and function.

Fig. 1 a-f

a and b. The IM.3-1931 head mounted on a black stand. The dowel in the neck runs parallel to the neck and gives the head a pronounced downward gaze (negative number 66113 and 66114, respectively; V&A, 1931). Burial deposits are still visible on and around the right ear; c. The head before the cleaning in the late 1980s (pre-1988; V&A, 2017); d and e. The head after cleaning and mounted on a light base, with dark plaster connecting the base to the lower portion of the neck (1988?); f. The interior layers of the head, following the removal of a copper dowel (1988; V&A, 2017).

Stucco: lime, gypsum or clay?

The term stucco is commonly used to describe a plastic material that, upon setting, hardens to a solid, dense material, which is relatively durable. The plasticity of the material allows it to be modelled and moulded in complex sculptural forms.

Despite its confusing and multiple definitions, and to maintain a continuity in the traditional terminology, in the context of this paper, the term stucco will exclusively refer to lime- (CaCO3) or gypsum- (CaSO4)-based compounds, which are the binding agent and whose properties can be modified by the addition of aggregates, such as sand and straw, and additives, such as organic materials, including gums, proteins, oils, etc. Therefore, earthen-based compounds, in which clays constitute the main binder, with the addition of aggregates and additives, will not be included in the definition of stucco. This terminology is therefore bound to create some level of confusion, as earthen-, lime- and gypsum-based compounds are commonly encountered together in Gandharan stucco sculpture, where an earthen-based core serves as a secondary support for the lime- and gypsum-based stucco; the secondary support, which is connected to a primary support/architecture, can also be made of stone, stone rubble, lime-based stucco, wood and other composite materials.

Methodology

A stucco head of the Buddha at the V&A

Physical history

On 30 June 1931, Sir Eric Maclagan writes to the Earl of Ilchester for advice, mentioning that he could not reach expert Sir Edward D. Maclagan, the President of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. After stressing that Campbell had praised the significance of the head, he adds that, because of the absence of his cousin E. D. Maclagan, he had showed a:

Ilchester’s first response is that the “the photo gave [him] a somewhat lackadaisical impression!”. However, after viewing the object, he writes: “The head appears to me to be the most remarkable, and as I suspected the photograph does not do it justice.” Importantly, he also adds that committees of qualified experts should be put in place to advise on acquisitions.

On 15 July 1931, just approximately two weeks after the head was presented to the museum, the director confirms the purchase, which is received with much enthusiasm by H. Spink the following day.

These exchanges provide an interesting insight into the perception of Asian art in the first part of the 20th century: the need for Campbell to refute the detractors of the art of Greater Gandhara and the comments of Lord Lee, despite the late date, appear to betray a lingering prejudice towards non-Western art.

Curatorial and conservation history

Since its purchase, the head appears to have been on prominent display as an example of Gandharan art. The earliest surviving photograph (1931) – possibly the very one attached to Maclagan’s letter – shows the head mounted frontally on a dark, square support, with the length of the neck running parallel to the supporting dowel, which is invisible in the photograph (fig. 1 a; see also another early view in fig. 1 b). The orientation of the dowel gives the head an inclined position with a markedly downward gaze. Figure 1 b clearly shows burial deposits on and around the right ear. In pre-1988 images, the head appears to be mounted with a similar orientation, but on a lighter base, with plaster connecting the broken section of the neck to the mounting block (fig. 1 c-e).

The record is silent until 1984, when John Larson, Head of Sculpture Conservation, requests for a “cutting of a limestone base block and fitting”. Conservator Kate Garland observes that there are “layers of grime covering [the] stucco and concealing [the] polychrome[y]. Also some fine clay concealing pigment – especially around the ears – has been excessively cleaned in the past, removing virtually all pigment”. Figure 1 c probably shows the head prior to the cleaning intervention in the 1980s. In this occasion, the surface of the head was “brushed with a dilute (3-5%) solution of polyvinyl alcohol (Rhodoviol 11-125, Rhône-Poulenc, France) to consolidate the remaining pigment” and cleaned under the microscope with swabs and de-ionised water. Greasier areas were instead treated with a “50/50 solution acetone/water”. In addition, “hot water cotton wool poultices were used on the cheeks and chin, were the grime was particularly stubborn”. The fine clay in the hair and ears was softened with water and subsequently thinned to reveal more pigment. The inner layers, visible at the back of the head and the bottom of the neck, were consolidated with Raccanello 55050 – an acrylic silane mixture, and a “dilute PVOH solution brushed on [the] surface to saturate pigmented areas”. Figure 1 d-f probably shows the head after the cleaning treatment.

In 1988, conservator R.O.G. Cook removed a copper dowel from the neck by chiselling out the plaster, which held it in place. In the conservation record, a photograph of the head shows the interior of the stucco (fig. 1 f). As this image probably corresponds to the 1988 intervention, when the copper dowel was removed, it may allow us to also date the similar photographs in figure 1 d and e to the same year. With an Ancaster limestone mount, which was inserted in 1988 and currently in place, the head is presented with a slightly different inclination, as the dowel is now roughly parallel to the main axis of the head, rather than the neck The head was assessed by conservator Victor Borges in the Scul